The printing press created facts by mass producing books and papers that were relatively difficult to alter w/o detection and could be traced more or less to a printer. Lots of what appeared in print was wrong, but it came with some authority and some authorities became the authorities that most people agreed to accept. We had the Encyclopedia Britannica for the almost erudite and the Guinness Book of Records to settle barroom disputes about the facts.

You could never be sure of a fact in the pre-print age. Most information passed by word of mouth. It was oral history, susceptible to unreliable memories, wishful thinking and ordinary mendacity. The written word was literally written. Each copy was different. Specialists can date manuscripts by the errors that have entered them. Think of it. You say something; I hear something else. We dispute what you said and neither of us remembers correctly. This is the pre-print world where everything is a matter of opinion and subject to interpretation.

Welcome back to this old world, brought about by new media. The Internet lets everybody “print” anything. Finding the facts on Internet may require a kind of triangulation. You have to compare different sources and then decide which version you believe. You can also alter what appears on the web. Well, technically there is a record somewhere, but you can “update” and perhaps overwhelm that. Truth often means what appears on the first screen of a Google search.

The general level of information has greatly improved. I am amazed at the extent of what you can find on Wikipedia and the accuracy is very good in many cases. Wikipedia is essentially an information market. It works very well when there are lots of participants w/o very much controversy. Where it falls down is where the market is thin (i.e. few participants to check and correct) or where there is enough controversy to attract lots of people with their own deceptive agendas. It never stands still.

I have a set of Encyclopedia Britannica. I used to love those books. I would just pull one out and read what I found, a kind of a random walk. I used to like to have the true facts. I am looking at my Britannica from my chair. They are nice books to look at, but they are no longer accurate. Populations have changed since this edition was printed nearly thirty years ago. Some whole countries have been created or disappeared. New things have been invented. My Britannica’s certainly are not worthless, but it would be very foolish to trust them on science, politics or current affairs. Actually, the only thing they are really good for is history. I am sure that they have not changed since I got them, so I can trust that those were the “facts” of around 1980. But overall I am better off with Wikipedia.

This makes me sad. I liked the idea that I had all the accumulated knowledge on my bookshelves, which now contain facts of antiquarian interest and opinion. On the other hand, I have the information of the world a few key strokes away. Decent trade, IMO.

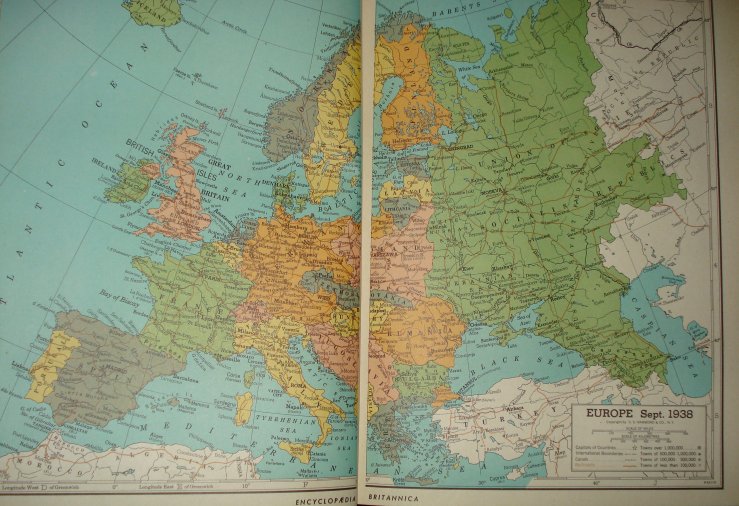

But it is still cool to have the real book, printed at the real time and touched by real people. Below is from my Britannica Atlas, which is older than I am. When this map was printed, during WWII, the editors did not know what the map of Europe would look like before the ink was dry, so they went back to the pre-war map, which was only valid for a few months. This map points to another print v Internet difference. This obsolete map is in my book unaltered. I can find the same map on the Internet, but I have to look for it. The Internet piles new information on old, like a sediment w/o outcropping. In a book, you might just find something intriguing like a map that doesn’t make sense and bids you learn more. In the Internet age, if you don’t dig, you don’t find.