I sense a subtle but important change of emphasis in the ICC reports on climate change that I think was evident in this “Deep Dive: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate” I attended today. There was plenty of gloom about the projections of the future, and there is plenty to be gloomy about. The earth is warming at a rate unprecedented in human history. Oceans are rising both from thermal expansion of the water and lately from the melting of terrestrial glaciers (melting of sea ice does not raise sea levels) and there is danger that the Antarctic ice sheets could join in, something not previously anticipated in this century. The change in emphasis that I perceived is a more practical approach. There is more emphasis on trying to figure out what we can do, both to mitigate and adapt, and less of ultimately fruitless search for blame in the past.

An iterative process is making the science better

An important factor, IMO, is that projections are becoming more precise. Science is an iterative process and with each iteration we get better, never finding final truth but getting closer to usable ones.

Introductions

Introducing the day’s program was Ambassador David Balton, Senior Fellow, Wilson Center and Pete Ogden, Vice President for Energy, Climate, and the Environment, United Nations Foundation. They laid out some of the facts I mentioned above and talked about the value of the new report. This is the first one to emphasis oceans and the cryosphere. These two were put into the same category more as an expedient than a plan, but their pairing was fortunate, since they are intimately connected. Water flows between them. Ogden talked about the usefulness of IPCC reports. The scientists do not make policy, but they inform it.

How the IPCC report function works

Ko Barrett, Vice Chair of the IPCC, talked about how the IPCC reports are produced. This one involved 104 authors combining 6981 studies and encompassing 31,176 comments. The report documents the thawing of glaciers and permafrost. Barrett explained that changes are coming too fast of natural systems to adapt. Humans can help, and we will need to adapt, but we need to mitigate change to slow it down enough that we can adapt. The oceans have been absorbing much of the heat of climate change, but marine ecosystems have been harmed (consider bleaching of coral) and there is a question about how long this can continue. Things often do not develop uniformly. Rather, natural systems feature punctuated equilibriums with tipping points of significant change. This is a risk.

Timely, ambitious and coordinated action are called for. In high mountains melting is evident. Smaller glaciers are shrinking, and some are disappearing. Glaciers and snow cover are reservoirs. Even if we limit greenhouse gas today, ¼ permafrost will be lost. This is already affecting arctic populations. Many low-lying islands will be under water.

She mentioned something I had not thought about – oceanic heat waves. Of course, it makes sense. Oceans have weather just like the land does. And the extremes are the issue, not the average.

The quicker and better we act, the better we will be able to address the issue

Next up was a panel discussion moderated by Monica Medina, Founder and Publisher, Our Daily Planet. First to present was Mark Eakin, IPCC Contributing Author. He talked about oceanic heat waves that cause coral bleaching. There have been three big bleaching events in recent years: 1998, 2010 and a long one 2014-17. The distressing fact is that this is still going on. Once coral ecosystems are dead, they take a long time to come back, even if the heat is abated. We are currently looking at big bleaching events around Hawaii and the Caribbean.

Robert DeConto, University of Massachusetts, Amherst; IPCC Lead Author, talked about his part of the report showing a set of charts, showing projections based on a low possibility, a blue curve with aggressive curbing of emissions, and a higher one, a red curve if current trends continue. We – and the world – probably can adapt to the blue line, red maybe not.

Sea level rises – thermal expansion and melting of terrestrial glaciers

There has been a change in why sea levels are rising. In the past, it was thermal expansion. Now it is more land-based melting. Greenland is melting from the top down. As it melts, it gets darker and absorbs more heat. There is more than 7 meters of sea level rise worth of ice in Greenland. An even bigger problem would be Antarctica. The danger here is sea level rise and the sea getting under the ice. Much of Antarctica is below sea level. It has been in the deep freeze, so it did not matter, but if water gets below the ice, it will be a bigger deal.

Adaptations requires mitigation, not a choice between them

Michael Oppenheimer, Princeton University; IPCC Coordinating Lead Author, picked up with what can we humans do about the problem. The big thing is to reduce emissions so that we are closer to the blue line. We might have a chance to catch up with this, to adapt.

Adaptation will include retreating from the coasts and allowing for natural buffers. There have been buyouts after hurricanes. Those who do not want to move away might build higher off the ground. We can also build protections, like sea walls. We can even advance into the sea, as they have in Netherlands. But a precondition for any adaptation is to mitigate.

Mr. Oppenheimer was very critical of subsidized flood insurance. This encourages building where it otherwise makes no sense. This is exacerbated by incentives that do not include preparations. The Federal government will help after a disaster, but fixing the system gets politicians no credit. People forget the last disaster and they don’t appreciate the disaster avoided.

During the question period, Mr. Oppenheimer talked about adaptation. Some of our coastal problems are exacerbated by climate change, but climate change is not the primary driver. Conservation of coastal areas in ecosystems like salt marshes and mangroves could be very helpful. These systems are themselves adaptive. It is an ecosystem-based defense. But we tend to destroy these things as much as protect them.

Developments in the high arctic

There was supposed to be a second panel, but evidently the only one to show up was Ambassador Kåre R. Aas, Ambassador to the United States, Norway, so Moderator: Sherri Goodman, Senior Fellow, Wilson Center, interviewed him. Ambassador Aas gave practical advice. We cannot solve all the problems at the same time, and so need first to address the worst or the ones that pay off the most. Fix the problem not the blame. Norway is working toward a no net carbon future, but in the meantime is a big producer of oil and gas. The Ambassador emphasized that using gas is better than coal, even if the long-term goal is to use neither.

The thawing arctic is opening up new opportunities and challenges. Shipping is become easier in the region. The Arctic Ocean is a kind of frozen Mediterranean Sea. If it thaws, ships can move. Resources are also an issue if the deep freeze thaws. The Norwegians are watching with some alarm the Russians on the Kola Peninsula. This is an old concern, made more current by climate change. But the Ambassador has observed that many people feel more threatened by the Chinese than by the Russians. China is no where near an arctic power, but they have strong interests in the region’s resources.

Ambassador Balton and Rafe Pomerance, Chair, Arctic 21, closed the program. Mr. Pomerance emphasized the need to get lots of people onboard, to build consensus. These are big issues that affect everybody. Solutions imposed, even if they are objectively sublime, will not be as effective as those brought about by consensus.

All things considered, an interesting discussion, encouraging despite the gloom of many of the facts. We have to continue our striving.

You can download the report at this link.

Don’t blame global warming

The problem with blaming global warming for everything is that it discourages better management practices that could be done, should be done to make our forests healthier. A good example are pine beetles. They are a problem and have been for years. They have become worse in recent times, and the facile explanation is global warming.

This article tells about how better management techniques slow the beetles. “As Dr Hood reports in Ecological Applications, the death toll was 50% in the control zone, 39% in the area intentionally burned, 14% in the one both thinned and burned, and nearly zero where it was merely thinned.”

Pine beetles are a threat in our Southern forests too. We know that the beetles are slow and stupid. When the tree are far enough apart, the beetles have trouble preying on trees and birds have an easier time preying on the beetles. That is a big reason we thin. Western forests are more often managed by the Forest Service and they more often are victims of misguided activists “protectors” who object to thinning or burning. As a result of the activists the forests are destroyed by insect and burned disastrously instead of in a better planned way.

So much of the destruction of Western forests is causes not in spite of the best efforts of activists, but because of them. Don’t blame global warming.

Reference

Other blog posts

Fire in Texas oak openings

Burning Questions

Setting the woods on fire

Burn the brush but save the soil

PINEMAP – southern pine and global warming

Global warming will create winners and losers. Among the losers are inhabitants of low islands. Southern pine forests look like winners, based on current climate models.

I learned some details from Dr. Tim Martin, who had worked on PINEMAP, a series of projects designed to study the effects of warming on forests and their possible role in mitigation of climate change.

Productivity in southern pine forests will rise with the projected temperature increase and elevated levels of CO2. Studies of slash and loblolly pine indicate significantly more growth, with the greatest gains coming from the northern part of the range. Beyond that, we can basically move loblolly genetics north, planting the more southern sub-species can be planted farther north. This has already happened to some extent, since many of the nurseries are in the south. A threat comes to these forests from an unexpected source. The climate change models indicate that parts of the great plains will become drier and less able to support crops. The SE is expected to be warmer and as wet, maybe wetter. Agriculture might move back east. Forests are currently planted on land not in demand for agriculture. They might be priced out of the market. But that is longer off.

Of course, making predictions is always dangerous too far out. The climate models have not proved completely accurate up until now. It is better to have lots of options than go with just one plan. The challenge is that the trees we plant today will still be growing decades from now, so we have to do now based on the most likely scenarios with enough variation to keep options open.

PINEMAP Pine Integrated Network: Education, Mitigation, and Adaptation project (PINEMAP) is one of three Coordinated Agricultural Projects funded in 2011 by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA). PINEMAP focuses on the 20 million acres of… pinemap.org

Earth history: temporate forest ecosystems in North America

http://prism2.si.edu/Pages/SI-WideArchive.aspx

I attended a symposium on temperate forests ecosystem at Smithsonian. Much of it was about earth history, deep earth history. When you want to look forward, it is a good idea to look back. Almost everything you can reasonably expect could happen in the future has happened in the past. Earth has been much warmer and much cooler in that past than it is today.

Climate change will bring ecosystems with associations of plant and animal that nobody has seen before, but it has happened before. We call them “novel” ecosystems. We can get an idea of the novel ecosystems of a potentially warmer future by looking at what was around during similar periods in earth history.

Emergence of flowering plants

Angiosperms, flowering plants, the plants and trees we are used to seeing around us today, developed in the early Cretaceous period around 160 million years ago. (BTW – the famous movie should probably have been called “Cretaceous Park” instead of “Jurassic Park,” since the lead dinosaurs were from that period, but that is another story.) Flowering plants developed in the tropics and then moved into temperate regions, first along riverbeds and in disturbed areas. Today we might call them invasive species. By the middle Cretaceous, they were globally distributed and often dominant and by 70 million years ago, many of our now familiar families of trees were well established. The details and relationships among species were different, but these ancient forests would look broadly familiar to us. This was one of the golden ages of temperate forests.

Then we had the mass die offs at the end of the Mesozoic, the same one that killed the dinosaurs. Around 50% of all plant species went extinct. The fossil record cannot tell us exactly how long it took, but it was quick in terms of geological time. Forests quickly recovered their diversity as the world got warmer, with tropical rain forests spreading up to 40 degrees North, about where Colorado would be and it got even warmer still with a boreal-tropical forest, where today we have cold northern forests. There were forests north of 80 degrees and paleontologists found fossilized stumps that indicate dense forests of trees resembling metasequoia (dawn redwoods now common in Virginia gardens) on Ellesmere Island, a place of permafrost & tundra today where nothing grows more than a few feet high.

Sudden greenhouse warming

A sudden greenhouse event brought rapid warming of 4-8 degrees C about 56 million years ago. This warm period lasted around 200,000 years, a long time to us, but not very much in the great scheme of geological time. Tropical vegetation moved far into what are now temperate or even cold regions. South America had vast eucalyptus forests.

Followed by a slow cooling

Eucalyptus in South America died out in during subsequent cooling phase. They are back in South America today, but the new ones are from Australia. A slow cooling began about 44 million years ago and we are still in that colder age. About 6 million years ago, we started to see periodic ice ages, as the Greenland ice sheet formed and glaciers advanced in the Himalayan highlands. What exactly caused the cooling is a subject of speculation. The leading theory is that it had to do with movements of landmasses that isolated the Arctic Ocean and allowed ice to form, the movement of the Antarctic continent to the middle of the polar region, where it could freeze more or less solid and the up thrust of the Tibetan Plateau, which cooled of the heart of Eurasia.

Data from the past is hard to get; data from the future is impossible. Natural history provides a rich mine of information about how forests will respond to rapid climate change.

The next speaker talked about associations of plants and animals. In times past, distributions of tree and plant species was sometimes different from what we see today. For example, today the ranges of ash trees and spruce trees do not much overlap. But in the Ice Age their distributions overlapped to greater extent. There is no natural association like that today. Difference in climate was not the only cause.

Strange relationships

Many “strange” mixes occur when there is a disequilibrium caused by big changes. The change in climate was one such cause, but not the only one. In this time in the past, large mammals (woolly mammoth, American camels, stag-moose, woolly rhinos, giant ground sloths and horses.) largely disappeared, probably because of humans showing up and hunting them to extinction, but there were a variety of factors at work. Although there is some dispute about the exact cause, (some scientists refuse to blame humans), there was clearly a disequilibrium created and it happened rapidly, in the course of less than 1000 years. Large herbivores play important ecological roles in that they eat and trample lots of vegetation. They are important in keeping open forests or grasslands free of trees and brush. When they disappear, forests close. And there is another knock off effect – fire. Fire is an herbivore. If animals do not eat the brush, it accumulates and eventually catches on fire. Humans would have increased the incidence of fire. There have always been fires, but the intensity varies. So what you see is greater variation, since the fires were more destructive when they came, but less constant than the grazing or browsing of the large herbivores.

The forests of 14,000 – 12,000 years ago were different from those of today for both climate and other land use reasons mentioned above. During the Ice Age there was greater seasonal variation than today with relatively hotter summers and significantly colder winters. For plants and animals in the environment, what matters is not the average, but the extremes. Something can be perfectly adapted 360 days of the year, but if the extreme weather of those last five days kills it, it will disappear. When you get extremes, then, it simplifies the environment, i.e. fewer species can find niches and so the forests are dominated by only a few species. You see that today in the difference between tropical forests, with thousands of species on every acre and boreal forests with only a few types of trees dominating vast swaths of land.

End of the last ice age, still changing

The Ice Age ended and the world warmed rapidly. Forests in North America again spread north to about where they are now. Our last speaker, Jonathon Thompson from Harvard Forest talked about more recent history.

The last 400 years has been a story of disturbance and recovery in the forests in Eastern North America. In Massachusetts, for example, deforestation peaked about 1850 and forests recovered rapidly until the 1970s, when urbanization started to equal or slightly exceed the rate of forest regrowth. The regenerated forests are similar to the old ones, but different in details such as age and precise composition. Newer forests, for example, are younger and earlier on the stage of succession. This is no big surprise. They just are not that old and more likely to be recently disturbed.

The composition is different

Researchers tried to get an idea of the former forest composition by looking at “witness tree” records. Witness trees were those used to mark property lines. They are described in some detail in old deeds. Usually, they would set down a marker and then describe the trees in all directions, in order to discourage someone moving it. Using these trees introduces some bias, since witness trees would more likely to be big and easy to spot, not a random distribution, but it gives some idea.

In the last centuries, there have been changes. Chestnuts are gone entirely. The chestnut blight explains this. Beech declined significantly, by around 15%. This is maybe explained by the age of the forest. Beech trees are late succession species, i.e. they are shade tolerant and start to come in when the forest is well established. Maples are more common now. The researchers went only to genus, and not to the species level, but they think there has been a big change among maples, with red maples displacing sugar maples to some extent. Oaks have declined, but not by that much and the same goes for hemlock, when not affected by the woolly adelgid. Hemlocks have been declining for 5000 years, however. They were once more common and evidently got some kind of stress thousands of years ago. The decline of the oaks may be an artifact of the study. Oaks are large and long-lived trees. They would be natural candidates as witness trees, so maybe they were just chosen more often.

Anyway, I learned some things I did not know and remembered other things that I had forgotten. Being able to attend such symposiums is one of the big advantages to working at Smithsonian.

Good Environmental News

The Economist runs an interesting section on the environment, pointing out that sound economic growth has proven the best environmental medicine. Wild rates of extinction predicted 40 years ago have proven exaggerated and rates are slowing. Similarly, predicted climate change is much more moderate and may even provide a net benefit by 2083.

Climate change is real, but it has been sort of “paused” for the last 17 years. Climate change experts have come up with many explanations. One might be that earth is less sensitive than they thought.

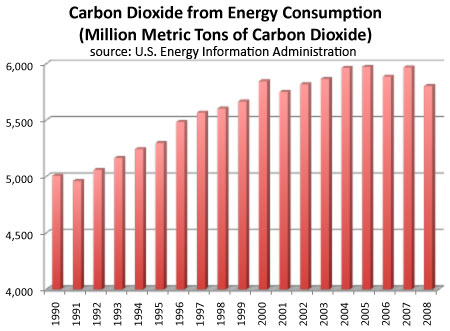

In any case, U.S. CO2 emissions have been plummeting since 2006. We will probably exceed our putative Kyoto targets in a year or two, not that anybody seems to care anymore. It was fun to bash the U.S. and GW Bush for not doing enough. Whatever we did was more than most of the others and it didn’t require all those laws and controls advocates so loudly demand so now they mostly keep quiet about it.

America has done all asked of it in reducing CO2 emissions and it looks like we are on the road to cutting even more by 2020 and beyond. And we did it without Kyoto. Now it looks like climate change will be more on the low side, we can adapt.

This is beginning to look like the other apocalypses I have survived. In the 1950s we were told nuclear bomb would wipe us out. In the 1960s it was the population bomb. We were supposed to be starving in the streets of America by around 1985. In the 1970s we faced global cooling and the wipe out 20% of world’s species by … about ten years ago. Actually between 1980-2000 we lost nine, not 9% – nine. Of course, we also had the energy crisis. By now we were supposed to have pretty much run out of fuel. All that new natural gas is evidently not there.

Think of those SciFi movies that used to frighten us. “Soylent Green”, that science fiction dystropia was set in 2022. “Escape from LA” took place in 2013; “Blade Runner” is supposed to be in 2019. I suppose it could get really bad by then.

I am not saying that the thing above, with the possible exception of global cooling, are not problems, but they are not the world ending things we feared. Population growth continues, but at a slower rate and will probably reverse within the lifetimes of some people alive today. Species are still being lost, but nature is adaptive and so are people. We have been saving more land and restoring habitats. Wildlife is returning or not wiped out. Brazil lost 90% of its Atlantic forest, but not a single bird species was lost.

IMO the biggest ecological problem we face today is not global warming but invasive species. My opinion has to do with natures adaptive ability. I believe that species will adapt to warming. But that same adaptive capacity in invasive species is already creating trouble all over the globe.

I am not suggesting we become complacent, but we can best address our problems by keeping calm and carrying on with our step-by-step improvements. The people who told us in 1953, 1963, 1973 … 2003 and now that we have to make immediate and radical changes have been wrong. Had we made radical changes we would be worse off. In any complex situation, it is usually better to try lots of things, check how they are doing, make adjustments and move forward again.

Life is better now for the average human being than in any time in human history. I am reasonably certain that it will be even better for our kids, if we don’t overtax them with SS (see below). So let’s continue to adapt and learn as humans have always done. Future generations is look at our urgent worries as we look at those of our parents and grandparents.

And I find that those who talk most loudly about the great problems tend not to solve problems at all, great or small.

Climate change challenges

My first encounter with climate change came when I was a kid in Wisconsin. We talked a lot about the Ice Ages and went on field trips to the nearby Kettle-Moraine State forest, where you could see the physical evidence of the ice age. The last Ice Age, in fact, is named the Wisconsin. It ended only 10,000 years ago. Until then, my native state was covered with glaciers. Then it got warmer and Wisconsin became the green and pleasant place it is, at least part of the year.

The Ice Age created most of our lakes and gentle hills. Glaciers did not cover Southwestern Wisconsin with its long hills and coolies. A coolie is a narrow valley formed by the scouring of melt water from the glaciers. Grand Coolie in Washington is a big example, formed when melt water broke through an ice dam, flushing everything before it from what is now Idaho all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Nothing like that happened in recorded human history.

Human history is a short time. We have just about 5000 years of history, i.e. when records were kept and there was no history in this sense in much of the world until much more recently. This means that our recorded human experience with climate change is very short and we recorded nothing as profoundly important as the rapid global warming at the end of the last Ice Age. But lots happened.

The Sumerian civilization, the people who first invented writing, were probably wiped out by a prolonged drought that lasted a couple hundred years. The Egyptians were driven into the Nile Valley by the encroaching Sahara desert. Mycenaean Greek & Hittite civilizations were destroyed at least partially by “climate refugees,” who moved in from places suffering rapid changes. The Philistines of Bible fame were probably among them.

On the plus side, Roman civilization flourished during the first and second centuries because of a generally warmer climate that pushed the boundaries of Mediterranean style agriculture and lifestyle into Germany and what is now the UK. This happy time ended in the fourth century and the sixth century had lots of especially nasty cool weather that brought with it famine and sickness.

We enjoyed another warm period in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. This was the period of the high Gothic, when European civilization flowered. It was significantly warmer in Europe, producing ample harvest and general prosperity. This ended with the onset of the little ice age. Frosts came earlier and lingered longer.People starved. The Black Death came around this time. While Black Death was not caused by climate change, the more desperate conditions caused by the cooling exacerbated it and hastened the spread.

None of these fluctuations in climate were evidently the result of human activity, but they had profound effects. I cannot point to a situation where climate was the only cause in the flowering or destruction of a civilization, but it was a big contributor to the rise and fall of Rome and the civilization of the high middle ages, mentioned above. There is an interesting speculation about the spread of the Indo-European language group found from India all the way to Ireland. Nobody has been able to find the original “homeland.” The closest many scientist come is Anatolia near the Black Sea. Some have speculated that it is UNDER the Black Sea. In prehistoric times, the theory goes, the Black Sea was much smaller and a fresh water lake divided from the salt sea of the Mediterranean by a narrow land bridge in what is today Dardanelles and the Bosporus. This eroded through, quickly filling the basin with salt water and pushing people up and out in all directions. The relatively rapid desertification of North Africa and the Middle East pushed people into river valleys (the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates) and in that respect contributed to the rise of the first civilizations. It is also important to recall that no climate change in recorded history has been as extreme as the end of the last ice age.

I don’t know if history should be a comfort or a terror when confronting today’s climate change. The earth has been much colder than it is today and much warmer than it will be in the next century with even the direst predictions. However, civilizations have risen and fallen on the backs of changes of smaller magnitude than we may soon experience. The difference is that changes in the past came as a surprise. People in the ancient Middle East may have noticed that game was becoming scarcer and the land drier, but given their short life spans and lack of good record keeping, it fell more into the realm of legend. We will be able to make increasingly accurate estimates of what is likely to happen. Nevertheless, we will be faced with the same choices our ancestors had. We can adapt in place or move.

Human civilization – ALL human civilization – flowered in the Holocene. This was an usually tranquil time in geological history. Some people have advocated that we call our most recent epoch the Anthropocene because it is so influenced by human activity. Certainly future centuries will merit that moniker. We have choices to make. We can look back on our history and earth history and see that it has been a series of upheavals and we have adapted to each of them. This tells us we can adapt to the next and we should do it sooner rather than later.

How to Manage Climate Change

Adapting to climate change is getting more sustained interest lately. The Economist magazine had a big story last week and NPR Marketplace had several stories this week. The impression you take away from this and other related stories is that we can expect pretty much nothing from all those international conferences, but the people are making decisions now that will help us all adapt.

“Marketplace” had a good article on Wednesday about the insurance industry and how they are adapting when they are allowed. Insurance rates are rising where risks are higher because of weather patterns. Insurance firms can work more efficiently. They don’t have to wade into the debate about whether climate change is man-made etc. They just look at the numbers and project costs.

Insurance and the ability to manage risk has been one of the most important, if unheralded, contributors to our well-being in the last couple of centuries. These guys figure the risks and then charge a differential which gives people incentives to be smarter. For example, if it costs you way more to get insurance to build a house on low ground, you move higher and avoid the risk. Insurance companies have been instrumental is improving fire safety, reducing accidents and making us all more healthy. But this only works when the costs can be passed to those who can affect decisions. Short-sighted politicians sometimes circumvent this process. For example, many areas of Florida are smack in the path of hurricanes already. No private insurance firms will willingly sell insurance to homeowners in some places, at least at rates they want to pay. This should tell us something. If a firm whose business it is to insure doesn’t want to sell you insurance, maybe there is too much risk. Unfortunately, the State of Florida has stepped in to offer cut rate insurance insurance for people who should move elsewhere. This is just like setting a time bomb that makes some people happy in the short run, but will create much more expense and suffering in the future.

I don’t know how much the climate will change. Nobody does. But there is no avoiding it as a general proposition. We don’t have to know all the details in order to know some of the steps we need to take. If we believe sea levels will rise, we sure should not expand construction in places that are already subject to flooding at today’s levels. Trees take time to grow. We should plant varieties of trees that are adapted to a wide variety of possible climates and develop new varieties. Buildings last around fifty years. We should make sure we are adapted. These things are not rocket science, just common sense.

We can live in a variety of places WITH the proper adaptations. We are not powerless. We renew our infrastructure all the time. It just seems permanent to us. Most of the buildings we live or work in are less than 50 years old, and among the older ones virtually none have not undergone major renovations. If we start now, much of the adaption can be almost business as usual. Just incorporate smart changes.

Most of us have trouble envisioning anything really different. We intuitively project the future in sort of a straight line from the present. It has never worked like that. We have a kind of punctuated equilibrium, with long periods of stability and burps of change. We have chances to adapt when times are “stable.” Once the change hits hard, it is too late.

I know that some people want a “collective” decision and that is what we will get. But it will be a collective decision by billions of individuals, firms and organizations. Governments will need to kick in some big infrastructure investments, but all should be made with an eye to the future, not simply saving things of the past. Adaption might often be hard, but it will not be impossible.

The picture up top is the Permian Basin in New Mexico. It used to be the bottom of a warm sea. It is higher & drier now. The Permian Period, for which this place is named, ended with the greatest mass extinction in earth history. Things change. Life adapts. We need to too.

BTW – I had to skate over the top of this issue, so as not to write way too much. If you want more detail, do read the “Economist” article. The EPA has a general report with some links. I also saw a couple of really good TV reports about adaptation to climate change. Unfortunately, they are in Portuguese. One of the specialists explained that the city of São Paulo has ALREADY warmed a couple degrees and storms are more severe. This is because large cities are ”heat islands”, i.e. buildings and paved surfaces concentrate heat. The city has been adapting to these changes, as we will more generally need to do.

National Climate Service

NOAA is establishing a National Climate Service, analogous to the National Weather Service. This is a good step for the very practical reason that it will facilitate planning and adapting to changes in climate. But it also carries with it the legendary pitfalls of prognostication.

You can listen to the NPR story about it at this link.

Weather predictions have become a lot more reliable in the last ten years. You can make reasonable plans based on hours of the day. For example, I was able to make drive across my state ahead of a blizzard because the weather service was able to accurately predict sun in the morning before the blizzard hit in the afternoon. Climate prediction is still not up to the scientific level of weather prediction, but it is getting better. We should soon be able to make reasonable predictions on the regional and sub-regional level.

This brings the obvious blessing that we can take advantage of changes and/or minimize losses. For example, as I have said on many occasions, it is positively insane to rebuild the below-sea-level parts of New Orleans. We should not extend subsidized flood or storm insurance to any new construction on low-lying coastal plains and we should encourage people to move to higher ground, even if that means building higher premiums into insurance policies and mortgages of those who won’t.

BTW – we DO NOT have to mandate this, if we just refrain from getting governments to subsidize or require insurance or mortgages be available at “reasonable” rates. The market will sort out which places are too risky. If someone is willing to insure your house on a mud-slope, it is his business and yours. People can build if they want, but we should not become accomplices to stupidity. We might also plan to retire some crops or cropland and get read to move into others. Advanced plant breeding and biotechnology will be a great help here.

Climate change will create winners and losers. Having a reasonable idea of the shape of the changes will make it possible to reap more of the benefits and suffer fewer of the penalties. But think of the troubles along the way.

Somebody today owns valuable land near major ports or in the middle of today’s most productive agricultural land. On the other hand, somebody today owns near worthless land. These might change places. Think of the ports around Hudson Bay. How many of us can even name one? If you look at a globe instead of a flat map, you can see that Hudson Bay is more convenient to many parts of Europe or Asia than is Los Angeles or New Orleans. The problem until now has been ice. The place was locked up most of the year. If this changes, so does the shipping calculation.

Are the current owners of prime real estate and infrastructure going to welcome all the newcomers? Are they going to welcome a study that shows investors and government decision makers a future that makes their wealth creation machines redundant?

Woe to the GS-13 bureaucrat who issues the report proving that no more government aid should go to New Orleans’ 9th Ward. Imagine how much more this will be true of more crucial and expensive infrastructure owned by politically powerful people and interests.

I think the National Climate Service is an excellent and useful idea. It will help us adapt and prosper in the future. But I fear the daunting politics.

I remember talking to a guy from North Carolina during disastrous floods a few years ago. He told me that they had detailed maps that could accurately predict almost the exact shape of a flood, but they couldn’t use them because people objected when the places they wanted to build were shown to be in the middle of seasonal swamps. We have seen this kind of stupidity in New Orleans and continue to see it.

There is a whole genre of literature involved with someone getting a prediction of future events and being unable to do anything about it. Predictors are dismissed (e.g. Cassandra) or often the twist is that the very attempt to stop the predicted event is what brings on the tragedy (e.g. Oedipus Rex). Let’s hope that our prognostication works out better.

So Far, So Good on the Climate Change Negotiations

The Obama Administration is exceeding our expectations at Copenhagen. Todd Stern, our chief negotiator has adroitly thrown cold water on developing county blackmail while our delegation makes the joyous noise with environmentalist. It has been an excellent balance of realism and hype that might actually lead to a workable agreement instead of the usual crap that comes out of these big convocations. So far, so good, let’s keep it up.

Calling their bluffs

Stern has called the climate community’s bluff, as we hoped he would. No more can plaintive voiced people get away with just saying how bad we are, how terrible things might get and – with a tears in their eyes – say that it would all be just great if only the U.S. would do the right thing. Stern pointed out that 97% of the new emissions will come from developing nations. Unless they step up, nothing will work. A little tough love was what they needed and what they are getting. One of our most potent tools is the resort to higher authority. This is something you learn in negotiations 101, but most people hate to use it. It does our egos a lot of good if we can say that we are the final decision makers, but it is a very bad negotiating position. It allows you to get rolled and/or carried away by the tide of events. This is what evidently happened at Kyoto. Otherwise it is hard to explain how our negotiators agreed to such a monumentally stupid agreement.

The negotiator proposes; the Senate disposes

How does the resort to higher authority work in this case? Our negotiators know and they have let other know that no matter what kind of agreement they reach at international venues, the U.S. Senate will have something to say about it when all the dealing is done. If the agreement is too absurd, the Senate will reject it, as the unanimous Senate did with Kyoto. This is a powerful incentive for everyone to be reasonable and not allow the exhilaration of the moment overpower the longer term realities.

Good guys and bad guys

There is another negotiation tactic that it seems that the Obama administration is using. That is the one we all recognize from watching cop shows – good guy/bad guy or good cop/bad cop. It is closely related to the higher authority gambit in that President Obama gets to be the good guy while the vaguely identified opposition plays the villain role. The incentive is to give something to the good guy so as to avoid rewarding or even having to deal with the bad guy. George Bush could never have pulled this off. He would have been undercut by the U.S. environmental community and, anyway, he didn’t have the persona to pull it off. Obama can. We all hope that he can swoop in at the end and scoop up some of the marbles that we otherwise would have lost.

America holds a strong hand this time

Addressing climate change is a big job and it will cost trillions of dollars. We agree on the goal, but there are ways to do it that are more and less effective; more or less costly and more or less costly particularly to the U.S. That is what these negotiations are about. And this is something that those most loudly braying about the need to “save the planet” are often trying to obscure.U.S. CO2 emissions relative to the rest of the world have been dropping for a long time. The blame America idea is just a non-starter. America is a big part of any solution, but if others, especially developing countries, don’t step up the problem cannot be solved.

Beyond that, everybody knows that the U.S. can more easily adapt to climate change than many others. Another bluff that many developing countries are running goes something like “give us money or we will drown ourselves.” That is another bluff we can call. America has more advantages this time than ever before. We should be fair but also tough. We cannot afford free riders. As we wrote elsewhere, the U.S. is now in a better position in relation to many others. We can plausibly promise real reduction in CO2 emissions, but it is very important how we sell reductions. You don’t give things away in negotiations because you get no credit in the international community if you just do the right thing w/o making a big deal about it. Multilateral negotiations are a kind of kabuki play. You have to scream and grimace at the proper times or else nobody pays attention. You have to call attention and claim credit for good things that just happen. You know that you will be blamed for the bad things.

Climate change talks should be about … climate change

We have to insist that the climate change programs remain about climate change. They cannot be sidetracked into a general push for development aid or some kinds of transfer payments from the rich countries to the poor ones. Many national leaders and NGOs come to climate change talks with the hope of hijacking them precisely in this direction. The threat of climate change has given them a potent weapon, which they are not eager to relinquish. That is why they often reject sensible solutions such as nuclear power or want to concentrate all their efforts on the developed world industries.

Physics doesn’t distinguish among emissions

So let’s keep on task. The job is to mitigate climate change and adapt to what we cannot mitigate. This is a practical problem involving lots of physics and physical infrastructure. The Chinese Ambassador disingenuously called for soul searching when talking about climate. If he can find a place to sequester carbon there, let him search his own soul. Otherwise the world’s biggest emitter of CO2 might just want to do something practical.

You have to be willing to walk away

Finally, the most powerful tool of negotiators is the ability to walk away from a bad deal. Developed countries like the U.S. accounted for most of the historical emissions, but they emit less than half of the GHG today and this percentage will drop now and forever. If current trends continue, China alone will emit more CO2 in the next thirty years than the U.S. did since 1776. China’s emissions alone more than swamps any “historical damage” done by us.

Nevertheless, many big and future developing polluters have a big incentive to play the victims. We already hear the silly rhetoric and attempts to guilt us into doing something stupid. (The Sudanese, you recall the guys who brought us the genocide in Darfur, had the guts to ask us to remember the children. Well, we do.) We should not let the idea that we MUST make a deal stand in the way of making a good deal. If many in the developing world have their way, we will send a lot of money with few or no strings attached to countries that historically have not managed their finances well. They will talk a lot about reducing CO2, but not do very much about it. In fact, the big buck infusion will enable them to pollute even more. This deal is worse than no deal and everybody has to understand that we will walk away than accept it. Climate change is an urgent problem and we need to find solutions. But rushing to do the WRONG thing will just make the whole thing worse. It is like the dishonest salesman who wants you to sign w/o reading the agreement. He tells you that if you don’t act right now, it will be too late. The deal will disappear. It is usually better to let a deal like that disappear. But the funny thing about negations is that if they know you are willing to walk away, the other side usually gets a lot more reasonable. The ABILITY to walk away usually means you don’t have to. The world will get a more effective climate deal if the U.S. is tough and realistic. Let’s not let another Kyoto mess things up for another decade.

Below are some sources you might want to consult on the climate debate.

Economist Special Report on the Carbon Economy

Negotiation 101 and Climate Change

“When you say you agree to a thing in principle you mean that you have not the slightest intention of carrying it out in practice.”* I have limited confidence in the efficacy of big global agreements, but I understand the usefulness of participating and we hope our team will be very forthcoming and aggressive in the COP 15 climate talks.

Forget Kyoto

The Clinton Administration never had any intention of implementing Kyoto. The Senate rejected it 95-0 before even being asked to ratify it. This was a unanimously bipartisan rejection of the climate treaty. Kyoto was dead on arrival, as the saying goes and it was indeed a seriously flawed agreement but Clinton was clever. He understood the dynamics of the public relations around climate change. Nobody really intended to carry out the terms of the treaty beyond the extent to which it was convenient. Most of the climate lobby was perfectly content if the U.S. went along rhetorically. Most of the major players were going along with the mendacious program. Bush didn’t understand how to play that deceptive game well enough and openly rejected the agreement & the U.S. got eight years of international crap as a result.

Take credit for what will happen anyway

Kyoto was meaningless. Developing countries got a free ride on the misplaced guilt of the more productive and hence more energy consuming nations (energy consumption is closely related to output). The former Soviet Empire was in the process of shutting down the horribly polluting – and without strong state protection – unprofitable industries built up during the benighted communist era. Countries in both these camps knew that nothing much would be asked of them and they might even be able to make a little money selling carbon they would not have produced anyway. The Russians were in the now even more enviable position of having been so horribly dirty and inefficient that any approach to normal would be rewarded with unearned credits and cash.

BTW – Russian carbon credits are one of the reasons ostensible carbon reductions in Europe were so cheap and ineffective.The Russians are now lining up to milk what they can out of Copenhagen.

Our European friends also came to the game with a few aces up their sleeves and a lot reductions already cooked into the pie when they signed on to Kyoto. In the British Midlands, they were in the process of converting from dirty coal to much cleaner and less carbon intensive natural gas. The Germans had recently acquired the outdated industry of communist-East Germany. They were shutting down these inefficient and very polluting industries anyway. It was sort of like a cash for clunker industries program.

The fall of communism in Eastern Europe was a significant ecological benefit all around. Just bringing industries up to non-communist standards resulted in a big reduction of all sorts of pollution. Beyond all that, they understood that Europe’s generally slower rate of economic growth would slow demand for new uses of carbon.

The U.S., in contrast, didn’t have any big shutdowns on the way and our economy was growing about twice as fast as those in continental Europe which would mean a growing need for energy.

Progress is on the way; revel in it and don’t sell it cheap

We are now in a better position in relation to many others. We can plausibly promise real reduction in CO2 emissions, but it is very important how we sell reductions. You don’t give things away in negotiations because you get no credit in the international community if you just do the right thing w/o making a big deal about it. Multilateral negotiations are a kind of kabuki play. You have to scream and grimace at the proper times or else nobody pays attention. You have to call attention and claim credit for good things that just happen. You know that you will be blamed for the bad things.

The free market is remarkably adaptive. When the price of gas rose in 2006, Americans used less energy and emissions of CO2 dropped. This is the only time this happened in a major country during a time of robust economic growth. Did we get any credit? Did anybody even notice? I had to look hard to find it in the media. WITHOUT the hyperbolic rhetoric you don’t even get credit for what you REALLY do. WITH rhetoric you can even get credit for things that just happen even if you do nothing. It takes a little dose of hypocrisy to make the world go around.

Now we’re cooking with gas

It gets better. We will soon be able to reduce carbon emissions w/o working up too much of a sweat. Technological advances in only the last few years have made available vast amounts of natural gas within the U.S. Our recoverable reserves have gone up by 39% in the last two years alone and gas is getting very cheap. As the economics of gas improve, we will switch from coal and oil, which emit much more CO2, to gas in many situations. This will reduce our emissions.

Natural gas is also abundant in areas of the U.S. much in need of jobs and investments.

There is an even better good news story. Last year the U.S. displaced Germany as the world’s largest producer of wind energy. Wind is still no big deal as a % of energy consumption, but the trend is continuing and abundant cheap natural gas can play a role. Wind is unreliable. You have to have a back up capacity. Gas is perfect for this. Unlike a coal plant, a gas generator can be easily turned on and off. On windy days, we would get electricity from wind. When the wind wasn’t blowing, gas would fire up to fill the demand.

Other alternatives plus better quality nuclear power is also coming on line. Match this with the generally slower economic growth we expect to suffer during the next couple of years (there is a silver lining to every black cloud) and you see that U.S. emission growth will slow and we may even have some actual drops. If you look at the chart nearby, you will see that the trend started down in 2006. We expect another huge drop of 5% in 2009. Notice from the chart that our emissions were a bit lower in 2008 than they were in 2000, w/o the benefit of Kyoto, BTW.

That means we can promise AND the United States can deliver. Delivering is important, but it is the promising that is the key to UN success. You need a lot of sound and fury in the international climate game. If we just deliver, we get no credit (cf. carbon reduction under GW Bush). In the international negotiating arena, especially international public opinion, what you say and how loudly & passionately you say it is at least as important as what you do.

We don’t have to take it anymore

The U.S. also needs to be in a stronger “moral” position to resist unreasonable demands by less developed countries. In fact, we can turn the tables on them. They always said, or at least implied that they were waiting for us, that if we (the U.S.) reduce our emissions they would do likewise. We are now holding the cards we need to call their bluff. We doubt most others will actually come through, but it will at least take some of the wind out of their sails when they make unreasonable demands on us. With our emissions dropping and those from places like China (the world’s largest CO2 emitter since 2006) and other developing countries on the rise, we can throw some of the stink in the other direction for a change.

The U.S. will be a leader in the effective use to climate change technologies

This is potentially a real game changer. With President Obama’s smooth rhetoric and proven ability to promise “change we can believe in” hitched to the real potential of the American market to take advantage of favorable energy trends and the unexpected bonanza of natural gas in the short term, we can cram a sock in the anti-American rhetoric on this topic. Yes we can.

Go boldly; no need to apologize

So let’s play hardball by “playing nice.” No need to apologize or send too much money to contribute to kleopocracies in developing some countries who use the poverty of their people and bad weather as bargaining chips. Instead, shift our weight and do a little international style jujitsu. We have little to lose, since we are on track to succeed anyway in reducing our emissions relative to the rest of the world, if we use the cheap natural gas we have found and ride the wave of innovation already coming our way. But none of it will count unless we make a big deal of promising. Posturing, promises & procrastination, that is how they roll at these kinds of international conferences. The rules of the game do not require and do not always even encourage actual success anyway, but we can both talk and do in this case.

Let’s do it and let’s also be seen to be doing it. It will benefit neither the environment nor us to allow another Kyoto to be hung around our necks. But with the proper nudge, maybe something can actually get done … even really about the environment maybe.

* The saying is attributed to Otto Von Bismarck