Most of us are willing to do things we like to do for little or no money. The payoff may be simple recognition. Passionate amateurs have made many great discoveries. Crowdsourcing lets us to tap into even wider expertise. It’s great if people are willing to contribute their time to worthy endeavors like Wikipedia, the search for intelligent life or other collective projects? Maybe not.

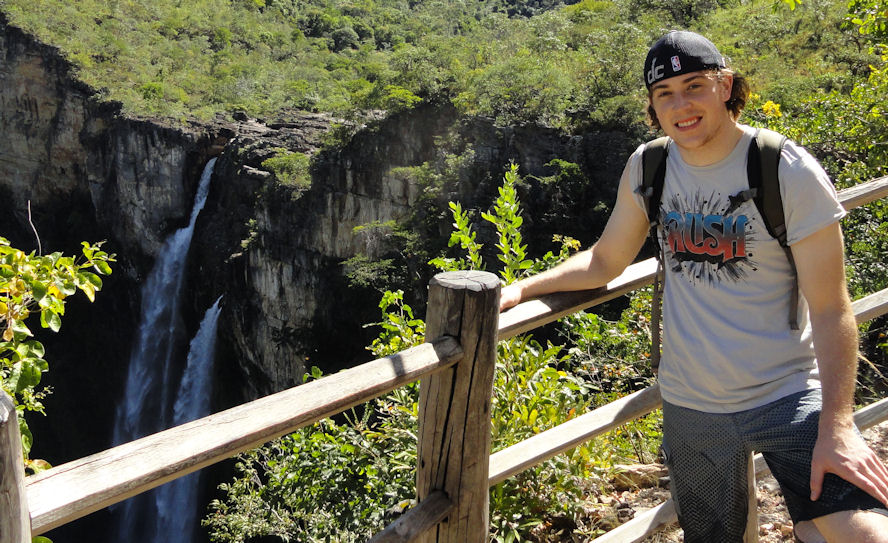

I take lots of pictures and post articles. All my stuff is “creative commons.” Sometimes people ask my permission to use my words or pictures; sometimes they just use them. I am happy just to be useful. Many of us are like this and it has been good. But the Internet’s capacity to aggregate information and make it available on massive scales may be making this virtue into a vice.

Think about those pictures. Some people used to make a living as photographers. Most of them really liked to take pictures, which is why they were in the business, but they WERE in business. They got paid for what they did. Those at the very top of the photography world still make lots of money. The rank and file photographers are being pushed out of the business by people like you and me providing similar quality at an unbeatable price – free.

This goes for lots of other creative people, such as writers, musicians or speakers and even teachers. The Internet dynamic here is similar. People don’t need to pay for the middle quality writing or music because it is all free on Internet. On the other hand, the Internet enhanced the power of the superstars. With the cost of each additional iteration of the product approaching zero, everybody will buy only from those they consider the very best.

There once was a market for artists who were imitative of the star musicians or writers. This niche is gone with the electrons. These semi-talented artists were subject to ridicule; they supplied the characters for comedy shows or Twilight Zone episodes, but they were able to earn a living. Today they give it away on Internet in the usually futile hope that their talent will be recompensed.

They may get significant numbers of fans or followers, but the currency of Internet fame rarely translates to real bucks in the pocket. There are enough winners in this game to keep the legions of suckers running the rat race, but it is a lot like basing your retirement planning on lottery tickets.

The danger is coming to teaching and universities with effective distance learning. We love the concept of being able to learn at our own rates, maybe to do so for free. This is great. But consider how it works. Take the Khan Academy. This is a great step forward in many ways. Millions of people will learn things they would not otherwise have known. A talented teacher like Sal Khan can reach millions of people. Never in a lifetime could he reach as many people as he can in a half-hour of recording. And this recording will never get tired. It can go on almost into infinity. It replaces millions of math and science teachers. It replaces millions of math and science teachers. Few of them were as innovative as Sal Khan, but they were part of a math and science community. The community which was once networked and diverse is now gone. Advocates will say that the Khan students are networked to each other and that is certainly one of the great strengths, but they are tied to the top.

Perhaps resistance is indeed futile and we should all assimilate into the greater good. More people will learn math or science. More people will hear great music or see great writing. But fewer people will be creating it. More correctly, lots of people will dronishly be creating things that nobody appreciates enough to pay for. A few, happy few, will be reaping the rewards of all this Zuckerburg style. Millions of Facebook users work for him and don’t expect to get paid. In fact, most don’t even know they are working for big Mark. I am not sure that Zukerberg knows they are working for him. He thinks he is giving them a free service. It is a perfect deception when even the deceivers are deceived.

I don’t have a solution to propose. I am guilty myself; I am an enabler. A few hundred people will read this blog. I have never met most of you; none of you would be willing to pay me for what I write and I don’t expect it. But I am aware of the dilemma. I am writing essays that in an earlier age would never be read by anybody at all. If I wanted to be “published” I would start with short essays or stories that few people would read, but my goal would be to find a big enough audience to make some money from writing. There would be a vetting process, but some people would make money for the type of thing I give away for free. I have a good job that makes me a “gentleman of leisure” who can engage in the luxury of writing w/o expectation of profit. But is it perhaps immoral NOT to make a profit? We dilettantes put would-be professionals out of business. Wouldn’t it be better if some poor suckers with talent but w/o a day job could aspire?

Those of you who were amused enough to read to the end perhaps can answer the question. You spent a few minutes with me. Thank you. We shared ideas. That is great. But maybe the hour I took to write this and the minutes dozens of you took to read it put some poor slob out of work. Not only that, it used to support an industry of others who were paid for what they did, critics, editors, printers etc. Now it’s just you and me. You can tell there is no editor. You can be a critic if you want, but you will get paid the same as I do and if you want to print this for any reason just push the button.

One of the promises of technology was that everybody could be published. But technology cannot promise that everybody will be read much less appreciated or paid.

I think we are seeing a kind of “Show businessization (new word)” of our world. Some actors and singers make fantastic fortunes, but the average actor or singer makes little or nothing from the profession. Many waitresses are aspiring singers and cab drivers have dreams of acting fame. The vast majority never succeed. It is not lack of talent alone. Many talented people never make it and some talent-free individuals become famous. There is a big element of luck, being in the right place at the right time. This is why all these aspirants spend time trying to be seen or kissing the asses of people who might give them a break. It is not pleasant and it is not a good society.

When you get this kind of competition, you end up with a tournament society where a few winners get fabulously successful and most of the others get bupkis. It is great in sports, movies and American Idol, but it is no way to live for most people.

BTW – I have been reading a book called Who owns the Future. That is what stimulated lots of these ideas and I suggest you read the book too. Give the guy a little money for his work and don’t depend on the free media.

Maybe we should be willing to pay a little for what we take and don’t expect somebody else to give it to us for free.