My Story Worth for this week.

Has an unexpected health problem changed your life?

Twice this happened. I turned out very positive when I broke my leg when I was 11 years old, as I have written before. No good has come from the second one, when I got aneurysms behind my right and then my left knee. The first one happened on February 6, 2012. I still have not made a full recovery.

I was running along Paranoá Lake & suddenly came up lame. Pain is nothing extraordinary for runners, but this hurt much more than usual. In fact, I had to get a stick to help me walk the couple miles home. But it was a strange pain. It didn’t hurt so much as create extreme fatigue. If I rested for about 30 seconds, it got better, only to get bad again when I walked again. I could walk only around 100 yards before the pain would get too big. February 6, 2012 was the last time I ran on trails.

Running had been a big part of my life for nearly 40 years. I started off on the trails along Lake Mendota in Madison. At first it was mostly for exercise, but it quickly evolved into something almost spiritual. I loved to run. I loved to listen to the sound of the gravel under foot and feel the rhythm of my heart with the pace of my feet, all the while drinking in the nature around me. I felt a relationship with the trees, the topography and even the dust rising from the ground. I understand that it was just my delusion, but it was a beautiful delusion – meditation in motion. I ran everywhere I went, and I went lots of places. I found all sorts of natural areas. Even in Iraq I found the joy of running. Then it was finished.

I probably should have had it checked out, but I just figured it was a really bad tendon pull. I could still ride a bike. The pain was not great when I rode the bike. I could not walk normally, but gradually I could walk farther and farther. It got better after a couple years, but not like before. Then it happened again in the other leg. I was driving down to Georgia for a Longleaf Alliance meeting. I though maybe it was just a leg cramp from driving, but it didn’t get better.

This time I went to the doctor. The first doctor told me that it was peripheral artery disease. Scary. I had none of the indicators. The doctors told me that I should walk more. They did not believe me when I told them that I commonly walked 3-5 miles on a typical day and rode a bike for many more. I had two options: I could have surgery or try to walk it off. Naturally, I chose the latter.

They also prescribed some blood thinners. It worked to a large extent. I walked as far as I could and then let my leg rest. Then I walked again. It took more than a year to get reasonably better. I remember this because I remember when we did our first burning on our longleaf. The DoF guys let me start part of the fire. I remember that my leg hurt not very much, but I was a little worried that I could not sprint away if the fire started to get over hand.

Today, I can walk for a few miles w/o too much trouble. My feet sometimes hurt, but I figure that is normal for a guy my age, any age. I run on the ellipse machine at Gold’s Gym, but I still have not tried to run on trails. When I have tried, my legs have hurt. I am not sure how I should handle this. Should I push through? I feel that I may have become too timid. This was not one of my characteristics and should not be. I can run on the machines. I can ride my bike and I can walk long distances. I think I can run again and as I write this I am resolved to do it again. I sure cannot hurt to try.

Anyway, this health problem made an impression on me. I guess before that malady I felt invincible, that I could just use will power to overcome anything. I was mistaken.

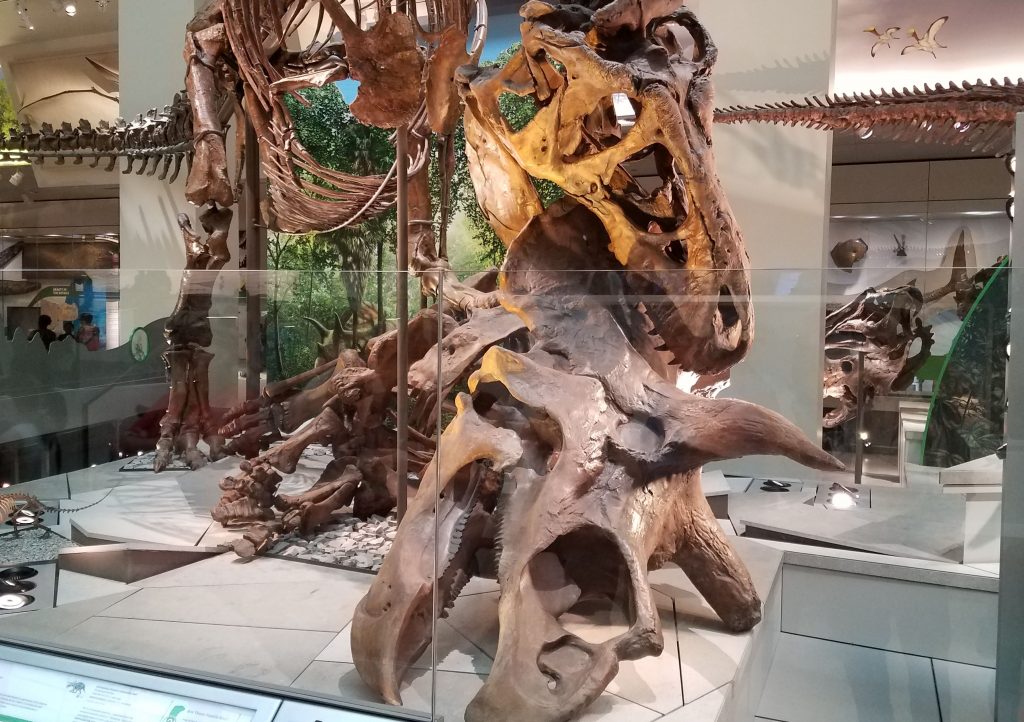

My first picture shows my the burning I was talking about above. Others are from the Mall. I worked a couple hours at State Department this morning and then walked along the Mall, stopping at Natural History Museum. First you see the bald cypress outside the museum. They have been there a long time, evidently able to overcome the constant traffic. Next is the museum itself. Picture #4 is a dinosaur exhibit, a tyrannosaurus rex skeleton eating a triceratops skeleton – nature red in tooth and claw.

Last is McDonald’s at SW. A couple of speculative observations. First shows people using the automatic ordering. Some people order on those machines; others go to the counter. I wonder if there is a demographic difference. I use the auto order.

This McDonald’s used to be a Roy Rogers. I used to eat there when USIA was in that building. When McDonald’s opened, they hired mostly local people. They were not very well prepared for work. Many tried hard, but it was sloppy. Shortly the local were replaced by immigrants from Ethiopia and Somalia. Today, most of the help seems to be from Central America. There is a kind of ecological succession of worker groups. It might be interesting to study, but I am not sure what use the information would be.