The question in any historical renovation is when. What period should be restored? In some cases the answer is fairly obvious. I stopped off at Montpelier, the home of James Madison. They just finished restoring it to what it was like when Madison lived there. Madison’s grandfather started the farm. His father built the house. Madison added a lot. Other people owned after that, including some of the Duponts, who greatly added and updated it. The restoration stripped away everything done after Madison owned it. That makes sense to me, but it is a value judgment.

Madison was the youngest of the founding fathers. He came prepared to the Constitutional Convention and is justifiably called the father of the Constitution. He deserves to have his house restored.

Hagia Sophia in Istanbul is one of the most interesting places I have been. It was the biggest Christian church in the world for more than 900 years until the Turks conquered Constantinople, killed or drove off the natives and turned the building into a mosque, which it was for almost 500 years. Now it is a museum. Should the Turks restore it to its original Christian splendor, when it had those beautiful mosaics or to the Islamic period when they were plastered over? The same sorts of questions go for almost any historical structure. But humans create more than buildings that change over time.

Below is a changing made-made landscape with non native animals (horses) near James Madison’s house in the Virginia hills. Not so bad.

When Henry David Thoreau talked about wilderness, he meant the kind of mixed forest and farm communities around Walden Pond. Today the forest has taken over much more of the landscape than in Thoreau’s time. Should historical sites in the Eastern United States restore the non-forested landscapes of the past? If you look at old photos, you notice that the landscapes have changed a lot.

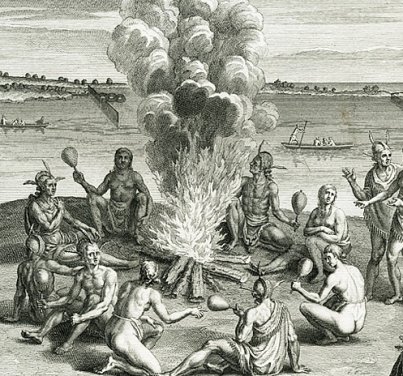

We talked a bit about landscape restoration in my forestry and prescribed burning seminar. Most people think the eastern U.S. was naturally covered with heavy forests in 1607. This is wrong. The landscape of pre-European was not natural and the forests were not so thick. Native Americans were enthusiastic users of fire for hunting, warfare and to manage landscapes, in addition to fire escape from cooking and campfires. Human induced fire shaped the ecology of North America for tens of thousands of years. The native populations, after all, had no comprehensive way to put fires out and there were no roads to act as firebreaks. As a result, grasslands and prairies extended well into regions of N. America that today support forests and forests were open and park-like. John Smith of Jamestown wrote that he could ride through the Virginia tidewater piney woods on horseback. You couldn’t do that today. Elk and bison flourished almost to the Atlantic coast because there was lots of grass for them to eat. The forests of 1607 were not like those we see today.

Settlers from Northern and Western Europe had less experience with fires as a tool for clearing land because Europe had been cleared long ago and their land was much more densely populated and intensely used. European peasants constantly searched the forests for firewood. They were not allowed to cut living trees, but could get any dead branches that they could reach by hook or by crook. They didn’t leave much fuel on the ground to burn. It was too valuable.

They quickly learned the native fire techniques. But with the denser populations, fire got out of hand. After a series of disastrous fires, such as Peshtigo fire in Wisconsin and the big blowout in Idaho and Montana, fire was stigmatized and it was government policy and popular preference to exclude fire from the woods. We pursued fire exclusion goal until around pursued until around 1970 and we still have not welcomed it back as a tool we should. Fire exclusion changed the landscapes, to include very thick forests and very different species compositions. These ecosystems were not being restored, since they had never been there. The Native Americans “immigrated” to North America before the most recent ice age. They brought fire with them and the continent has been burning ever since. Remember that nature starts fires in only two ways: lightning and volcanoes. There are no volcanoes in eastern North America and lightning tends to come in the summer, when humidity is high and plants are lush. It also usually comes along with heavy rain. In other words, natural fires are much rarer than the regular burns we find in the natural and archeological record over the last 10,000 years. Humans accounted for most of the burning.

So the question about restoring the American landscape is when – what period? What period should we restore? Should we restore at all, or maybe strive for a richer, more diverse landscape? We have lost some species and gained some others. (Most of us like horses, sheep and cows, all non-native.) We have a better understanding of ecology than any of our ancestors and we have improved tools. There are some natural places with special value. These we should choose the appropriate period and “restore” them as possible. However, overall we cannot restore how it was and probably don’t want to. There is no ideal past. We can do better.