It is easy, maybe even stylish, and certainly popular to dismiss our government officials as self-serving, incompetent or both, but it is not true. Sure, as in any human endeavor, there are those who are just in it for the prestige, power and/or promise of future gains.

However, most, in my experience, are good people trying to do a good job. I try to listen to what they say, beyond the sound bites, when they are trying to explain the basis for what they do. I was impressed, for example, with Interior Secretary Sally Jewell and her understanding of energy, especially fracking, and her commitment to managing our lands.

Yesterday I attended at talk by FTC Commissioner Maureen Ohlhausen with what seemed like an unlikely title: Regulatory humility in practice. In fact, the title is what drew my interest. The moderator joked that many thought it must be an April fool joke. Since when is there humility among regulators? She gave a good talk. Starting with a classical allusion, which impresses me.

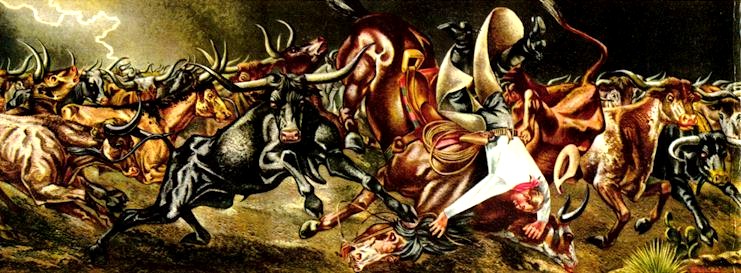

She talked about Procrustes. In Greek mythology, Procrustes was an innkeeper who liked things orderly. He had a bed that was exactly the right size. If guests were too short for the bed, he stretched them until they fit. If they were too tall, he cut off their feet. Regulators, she averred, were too often like Procrustes. They forget that the purpose of regulation is to improve conditions, not make people fit their preconceived notions of perfection.

Regulatory humility is simple to postulate but hard to practice. Regulators need to know their limitations, prioritize to protect against real, not hypothetical harm, and use the appropriate tools to correct the problem. As I wrote, simple to postulate, but making it work violates many of the laws of bureaucratic physics. Nobody gets rewarded for knowing their limitations and acting on that knowledge. I know from my own experience that more credit comes from “great ideas” and project beginnings than from successful conclusions. It takes real effort and significant self-abnegation not to play the game.

Ms. Ohlhausen pointed out some of the reason why you have to be careful with limitation. One is that you cannot know all the factors involved. Regulators do not have the time to collect and analyze all the information and even if you did you probably could not understand it. Furthermore, in a fast changing industry, information is quickly out of date. If you knew everything there was to know about Internet in 2010, you would be pretty much useless today.

Some knowledge is being created by those doing the stuff and much of it is “tacit knowledge,” i.e. the people doing things cannot explain exactly how they do it and nobody can learn it sufficiently in theory. I ride my bike all the time. Yet I have no idea how to explain how I stay up. I could look up a physical explanation, but that would be unhelpful and it is obviously unnecessary for a bike rider to know. A rule based on that physics that tried to tell me how to ride would be just as useless and unnecessary.

Even with all these caveat, however, regulators like to regulate. It is what they do. They need to identify places of real harm AND place where regulation can produce real good. We can identify many bad problems that do not have workable solutions. It is tempting to take action, to do something, but that could be wrong. Regulators should work incrementally and transparently, correcting when things do not work as planned or when secondary consequences make the whole enterprise a net loser. This is the hard part. People understandably want certainty, or at least the appearance of it. A system that adapts to conditions and allows learning usually works better than a rigid one, but it is by its very nature uncertain. Regulation may create certainty by freezing in place the current situation. This may be okay, even desirable in some places, but certainly not in others. It would not have been a good thing to freeze the Internet in place ten or even five years ago. Innovation is unpredictable and usually messy, but we do need it.

BTW – these lectures feature a modest free lunch. I sat down in a good seat and introduced myself to the others around me. One guy just mumbled and gave me a furtive look as he continued to eat. Just before the start of the talk, he picked up his stuff and walked quickly away, never to return. I know that there are those who attend events mostly for the free lunch, but it is churlish to take the food and not listen to the talk, especially because the guy took a place at the table. Others, of course, could fill in, but it is somewhat awkward to get up and move in like that.