Most people are uncomfortable with the exercise of authority and they usually resent those who do. Lord Acton’s observation about the corrupting nature of power still applies. (“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.”

Nevertheless, establishing order requires authority and w/o basic order, nothing much gets done. Power need not be overly coercive and the most effective leaders are those who welcome the participation of other. I have written on this subject on many occasions. But sometimes you come to a bottom line where a decision must be made. In those times, a leader who refuses to make the hard decisions is shirking his duty.

Leaders who refuse to lead are the leading cause of unhappiness in the workplace, IMO. Worst of all are the guys who won’t lead, but like to boss. Next worse are the ones who hide among the rules. Rules apply to most situations and all routine decisions. You need leadership for those times when they don’t. Leadership requires the exercise of judgment, which will always seem arbitrary to those who disagree.

I learned an interesting lesson from an exercise in my leadership seminar last year. Reference this link for details. I don’t think it was the one intended. I was chosen as a group leader by a more or less random and unfair procedure. In the exercise, points were distributed based on rank but were also earned by individual and group effort. I determined that our group could score lots more points if we cooperated and with my two leadership colleagues, we created a system that distributed the points fairly. The facilitators were surprised and (I think) a little chagrined that we were scoring so many points w/o dissention. We soon got dissention, when another group used the rules to seize power, despite the fact that it cost us all points. The lesson I took was that the essential task of power is to maintain it. Nasty and Machiavellian as it might seem, the simple fact is that you cannot accomplish your goals (even if your goal is to pass along power to someone else) if you are deposed. Weak leadership does nobody any good.

I am reading a book Alex gave me for Christmas called Rubicon. It is about the fall of the Roman Republic. The author is very talented, but he evidently doesn’t like the Romans. His description characterizes them almost as an infestation that infected and ultimately destroyed the ancient cultures of the Mediterranean. Their virtues of perseverance, bravery and patriotism are seen as merely enablers of their cruelty. A couple months ago I finished a book called Empires of Trust, which left almost the opposite impression. I have been reading Roman history for a long time. They are both right. The Romans established the greatest Empire in history and brought order, a degree of justice & prosperity to the lands of Europe, Africa and Asia that surrounded the Mediterranean and now are thirty-six separate nations. They were brave, resolute, consequent and practical. They were also cruel, mendacious, superstitious and capricious. In other words, they displayed all the usual attributes of power.

I admire the Romans, with all their faults. Our world is very much based on theirs. Our American constitution embodies many of the lessons of Rome, only better. I believe in progress and that sometimes we can learn from history. We learned from the Romans and we can be better than they were because we stand on their shoulders. The fatal flaw of the Roman organization was their messy succession procedure. Augustus established the principate (became emperor) through stealth and maintained it with the fiction that he was merely the first among equals. He is recognized as a political genius and a great man for his achievement and it was probably the only way to pull it off. But it avoided some of the responsibly of power and made each transition an unpredictable adventure which often involved murder and the exercise of military muscle.

The Romans were hated and justifiably feared because of their power. They deprived the people of the Mediterranean of political freedom, what we would today call national self-determination. If you annoyed the Romans, you paid a high price. But the Roman Empire provided a great deal of liberty, tolerance and personal autonomy. (Of course all ancient societies were horrible and oppressive by modern standards. Remember that progress thing. But compared with the available alternatives, you were probably better off living in the Roman Empire than anyplace else in the world at the time.)

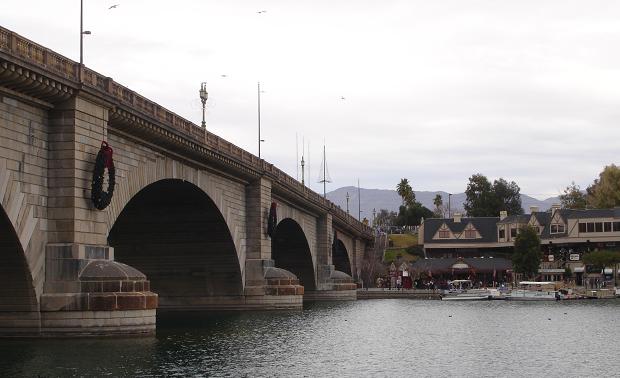

Above – Romans perfected the dome and pioneered the use of concrete in buildings. Most of my ancestors were among the barbarians who destroyed the Empire and I imagine my grandfather many generations removed scratching himself in the Forum trying w/o success to figure out how all that water got to the fountains. The Empire fell in 476 in the West (although it hung on until 1453 in Constantinople) but the idea of Rome persisted and the whole world is heir to their achievement. You can see it in architecture from Shanghai to Seattle. Washington looks a lot like a Roman city. The Romans were not very original, but they were experts at assimilating and developing ideas from a diversity of sources. They developed what became our concepts of rule of law, citizenship, the concept of a republic and separation of powers, so we Americans are especially indebted to them. Our Founding Fathers knew what we sometimes forget.