This book seemed written just for me, what with all the references to fires.

The three authors – Tim Geithner, Bob Bernanke & Hank Paulson represent Democrats, Republicans and career scholars/civil servants. They are the men more than any others who saved our economy and they tell their story very well.

Learning from history

The economic crash that started at the end of 2007 and ended early 2009 could have been a lot worse. The Great Depression started like that. Fortunately, this time some people had learned the lessons and the Treasury Dept, the Fed and even politicians did mostly the right things. The authors thought it useful to document some of what happened in hopes of making the lessons available for the next time we have a panic – and there will be a next time.

Metaphors explain

The authors use a few metaphors that make sense. They describe the spread of economic panic like an e-coli scare. There is some tainted meat or lettuce. Most is just fine, but people avoid all of the products, good and bad. As the panic spreads, it gets worse because unlike e-coli, which is a identifiable pathogen, financial markets depend on confidence & trust. When confidence & trust are lost, perfectly good securities can become toxic, leading to more loss of confidence.

Value is only what others are willing to pay

Nothing has intrinsic value. The labor-value of goods, i.e. something value depends on the work that went into it, makes intuitive sense, but it is a false concept. The only thing that gives anything value is what somebody else thinks it is worth. Housing was the basis of the collapse. People had confidence that home prices could go only in one direction – up. So, people bought more house than they could afford, assuming the value would grow, and they would make money. It seemed risk-free. They did make money for a long time. But your home did not get to be worth more unless somebody else is willing to pay more. In fact, the home we bought in 1997 should be worth less, since some things have worn out. Yet the value increased because people were willing to pay. When this stopped, the economy went down. The home that was “worth” $500,000 when you bought it, suddenly was worth half that. Even if you still owed $450,000.

The conflagration consumes good, bad and neutral

The other set of metaphors the authors use is fire. They use it in two related but separate ways that I think reflects Bernanke and Paulson. Bernanke talks about house fires. He gives the example of moral hazard. If a person smokes in bed and sets his house on fire, he may be blamed for the conflagration. But it doesn’t do any good to punish him by letting him burn, if your house will also catch fire. He used this metaphor to explain why we had to bail out some people who made bad, or even dishonest decisions.

Paulson is an environmentalist, who has exposure to prescribed fires and forest fires. His fire analogy is that of a wildfire. Whatever sparks the actual fire is less crucial than the presence of dry material ready to burn. Trying to identify the people or thing responsible for the ignition is a useless exercise, and trying to protect the only by stopping ignitions is worse than useless, since the task is impossible but might lead to complacency about address the kindling conditions.

Anyway, the fire was burning and destroying good as well as bad assets.

Bush & Obama did the right things but got little credit …

The authors describe the actions taken, much of it by the Fed and Treasury to shore up assets. They remind us how controversial all this was at the time, but our leaders showed courage. TARP (Trouble Assets Relief Program) was passed by a Democratically controlled congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush and they did this in the middle of an election campaign. And it was George W Bush who bailed out the auto industry. All this worked out. In fact, the government actually made money on these transactions.

… and a lot of blame from their own folks

Activists on both sides of the political spectrum hated the programs, however. People on the right didn’t like the idea of spending government money to bail out firms because they feared the expansion of government. People on the left didn’t like the government bailing out firms because they wanted more government and wanted to punish private firms. In the end, the more moderate middle saved the county.

The authors praise both the Bush and Obama Administrations for going against the power of their base. Bush embraced greater government. He also took many of the hard decisions in the lame-duck part of his presidency, sparing the Obama folks the opprobrium and the attacks they would have suffered from opponents opportunistically blaming the new guys.

The Obama folks, for their part allowed the Bush team the room they needed AND carried on similar policies when they took office. This is less surprising when you recall that Geithner, part of the triumvirate fighting the economic fire, became President Obama’s Treasury Secretary and Bob Bernanke stayed on at the Fed until 2014.

Obama did not follow the sirens’ song of his own base that wanted to make a clean break with Bush policies. In fact, this was a rare case of a nearly seamless transition, as 2/3 of the leadership team and most of the professionals remained on the job after the election.

This is how it is supposed to work. It is not how it worked at the start of the Great Depression and we got … the Great Depression. This time we got a severe downturn, but by summer of 2009 we were swinging back, even if that was not immediately evident to most Americans.

The future is uncertain.

The authors give advice on how deal with future panics. They warn that while legislation and regulations in place make the ignition of panics less likely, the mechanism to deal with them are less robust. They say it is like vaccinating people against deadly diseases, but at the same time closing hospitals.

It will happen again, and we will not be ready.

There will be other financial panics. By definition, they will come from unexpected sources, since we expect the expected ones and have covered those bases.

There is a kind of Stoical aspect to this book. Misfortunes will come. We will need to deal with them, but we cannot really say how. And there is an irony. Sometimes our preparations CAUSE the problem. We prepare for or regulate against one thing, and it creates incentives to do others. Making the system safer, for example, encourages more risk taking, making it more dangerous. We need to maintain a robust system, not one that is immune to all the troubles we can imagine, since the trouble of the future will be those beyond our imaginations.

Still encouraging

I was encouraged by this book and comforted, despite its rather gloomy recognition that something will happen, and we will not be fully prepared. I was encouraged by the competence and commitment of our leaders. They don’t get much praise these days, but when they chips are down, they step up.

Another lesson. It takes human judgment and courage to deal with unexpected big problems. The routine rules are set up for routine situations. When we go beyond that, somebody must decide when to go beyond in response.

The substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things unseen.

What influences us? We often do not know because very profound influences come in small packages.

The picture above is a good example. I took that picture more than ten years ago (October 2009) at a conference on creating bobwhite quail habitat. I took the picture because I thought that open woods was just beautiful and I was learning that it was very productive for wildlife. It reminded me of the open ponderosa pine landscapes of the west.

I have referred to that picture many times and its influence on my choices has been significant. It informed decisions on thinning my the pines on Brodnax and Freeman. I sacrificed some timber value for wildlife and aesthetic reasons. Having that picture in mind helped me … well visualize the result.

In the ten years since that picture, I have learned a lot more about forest ecosystems and the forest-grassland savanna of the American South. Back in 2009, I had not yet planted my first longleaf pine and I really did not know much about that ecology. Now that I know more, my vision for the future is more longleaf than loblolly, with more complexity on the forest floor, but the picture still is similar.

I need that kind of inspiration, that visualization. I will never see the results of my efforts. I can only hope that my kids, or other future owners of the land I have come to love are willing to carry on.

St Paul defined faith as “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” I have often been inspired by those few words. My forestry work certainly is faith-based, but I am glad to have a glimpse of something like what I will not get to see.

Christmas 2019

Great family meeting

Old man and the woods

I take great joy in my forestry for many reasons. It connects me. I feel part of something that I can both control and not. The paradox of human existence is summed up in the work in the woods, beyond my understanding but still within my grasp.

There is a more prosaic and practical thing that I love about forestry. A curse of old people, a group I now count myself, is to worry about becoming irrelevant, losing my memory and being unable to learn new things. The dog barks but the caravan moves on. I do feel mentally slower than I used to be, but maybe I just recall being cleverer than I was. Life is often remembered better than it was lived. My practical reason for loving forestry is that it proves that I have not lost it.

Old dog and new tricks

I know a lot about southern ecosystems, fire ecology and the business of timbering. I do my own planning, contracting and land management. I know for sure that most of these are things I did not know when I was younger and smarter, i.e. all of it was newly learned after I was well into middle age. For example, when I was going to buy my first forest land, I asked the seller what kind of trees were growing there. He told me loblolly pine. I had heard the name, but I was unfamiliar with the species. I could not tell a loblolly pine from a longleaf pine, from a Virginia pine or even from the red pines I knew from Wisconsin. I still have trouble telling a loblolly pine from a pond pine, but I can identify them, get a fair estimate of their age and know a lot about their patterns of growth. I can even identify loblolly by their smell. All of this is old man knowledge.

I am not here to tell you that working in forestry keeps me young, but it does keep me more vigorous in mind and body than I would otherwise be.

Don’t give a f*ck

Owning my forest has also given me a “don’t give a f*ck” attitude toward lots of other things in life. I have my woods and I care a lot – I care passionately about everything related to my woods. But that allows me to dismiss lots of other things. I know that it infuriates some people that I am not deeply offended by Trump, not concerned with social justice or not even very concerned with making more money. I just don’t really care, and I don’t really care if others are offended that I don’t really care. This is a new feeling for me. I used to be much more concerned with what other people thought of me. Don’t get me wrong, I like almost everybody, even people who don’t seem to like me. I try to be generous and have good manners. I try never to offend unintentionally or take offense easily, but I can pursue “deep” discussions on all sorts of sensitive subjects with a disinterest that I never felt before. (Please note that disinterest is not the same as uninterest.) I often think in terms of “this too will pass, but the trees will still be here. The world’s problems are not mine, except as a disinterested observer.

Should I care more?

I have considered whether this is an abdication. As a recovering historian of ancient Rome, I have sometimes wondered whether the detachment provided by Stoic philosophy common among Roman aristocrats contributed to the decline of civic virtue. I want to participate in the life of my country, as well as the life of my forest, but I worry that I do not have the passion for politics that I once did. Political participation used to be fun. Now it is more like a duty.

Anyway, those are my old woods guy thoughts. I still like to write, even if I don’t think many people will read it. I hope that pleasure does not diminish.

My picture is an old one from my earlier life, one I still look back to with pleasure but now detachment. I met a guy in Bahia, Brazil. He was simply called “the Poet”. He lived in the woods, observed nature and wrote poetry about his observations. Seems a very happy man and a balanced one. He made an impression on me. I liked what he was doing. I am not a poet, but I do love to observe nature … and participate with it.

Checking the fire on Freeman; planning on Brodnax

I got all the longleaf in the ground. There were only 334 total. I thought there were a few more, but I still almost didn’t finish. I spent too much time cutting brambles to get ready for the next planting, so the kids will not have to suffer too much. I also went over to the Brodnax place to talk with Adam Smith about the next burning there. We have make a fire line to the stream, which will provide the stop the rest of the way. See the picture. The water if very clean, so the SMZ is doing its job.

The other pictures are from Freeman. Science and experience tells me that the trees are okay, but it still scares me a lot to see all that scorch. Funny how trees next to each other can have such a different fire experience. I checked that really scorched one, the lower branches, more scorched. You can see in the last picture that the green bud core is intact. I figure if the lower ones are like that, the higher ones are too. But I will be more content in March when I can confirm the new growth.

Checking on Freeman fire

I was surprised and delighted to find that I could get a box of Virginia longleaf, so I drove down to the Garland Grey nursery and then on to the Freeman place to plant them. We still will be getting 3000 more from Bodenhammer in North Carolina, but it was good to put another 344 (that was the number in the box) trees into the breach. I enjoy planting the trees, even if it takes me a long time.

We will see if the Virginia trees behave differently from their North Carolina cousins.

I also inspected the results of our fire. My 2012 longleaf are scorched. This would terrify me, but I experienced this last time too. They will be fine. I checked for the green leaders and they are there. Still and all, even though science & experience tells me all will be well, I wait anxiously for March to see it so. They are a pretty color at least, as you see in the picture. I have included a picture of those same trees after they were burned in 2017.

My other picture is one of my mistake shots. As the picture shows, I just yanked off my boots and was getting my phone. I think I will make compilation of the various times I have pushed the button wrong and got pictures of my shoes, hands or just the ground.

Forest Stewardship Plan Diamond Grove Tract

Forest Stewardship Plan for John Matel and Christine Johnson, Diamond Grove Tract

Forest Stewardship Plan for

John Matel and Christine Johnson, Diamond Grove Tract

Introduction

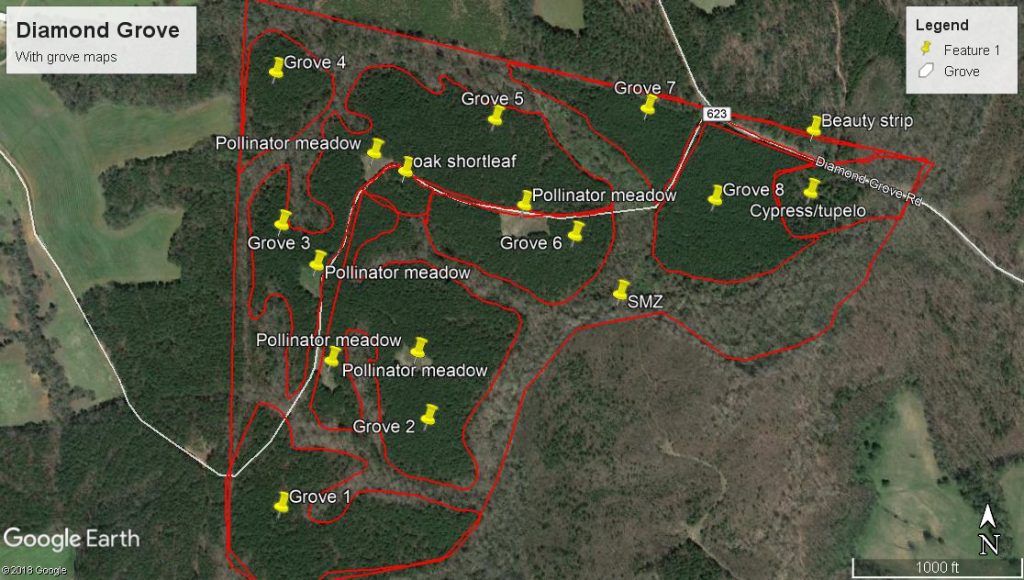

This Forest Stewardship Management Plan covers of approximately 178 acres of forestland in Brunswick Country, on Diamond Grove Road (SR 623) just north of Genito Creek, near Brodnax, Virginia. The tract map is included.

The tract is mostly low hills. It includes approximately 110 acres of loblolly pine plantation planted in 2003. The loblolly pines were thinned pre- commercially in 2008 and biosolids were applied that same year. The tract also includes 2 acres of open field (grasses, forbs and flowers) first established in 2007 and maintained for pollinator/wildlife habitat, 6 acres covered by roads and 50 acres of steam management zones and/or areas frequently flooded. The land was cleared for agriculture at one time but has been mostly forest for at least 80 years.

Overall wildlife habitat and forest health are maintained and improved by thinning, burning/mowing and planting feed and pollinator habitat in patches in the woods and along roads, and maintaining soft edges. Most of the roads are covered in grass and forbs, with a big component of lespedeza.

No endangered species of plants or animals were noted on the tract.

Forest Stewardship Management Plan

Landowners: John Matel & Christine Johnson

8126 Quinn Terrace, Vienna, VA 22180

Telephone

Forested acres: 170

Total acres: 178

Location: Brodnax, Virginia on Diamond Grove Road (SR 623)

Prepared by: John Matel

This Forest Stewardship Management Plan is designed to guide and document management activities of the natural resources on the property for the next ten years, in harmony with the environment and will enhance and regenerate the ecologies on the land.

The Goals for Managing this Property:

- Produce forest products sustainably

- Soil and water conservation

- Encourage diverse and productive ecology

- Restore oak/shortleaf pine ecology in upland section

- Restore/establish bald cypress/tupelo ecology near creek

- Improvement of wildlife habitat.

- Experiment with patch burning for wildlife

- Maintain soft edges near roads and stands

DESCRIPTIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS (Acreage approximate and do not sum to total)

Grove 1

Acres: 20

Forest Type: Loblolly pine planted 2003

Species Present: Loblolly & shortleaf pine, ailanthus, American sycamore, sweet gum, yellow poplar, eastern red cedar, hackberry, Virginia pine, mockernut hickory, white oak, chestnut oak, black oak, green ash, mulberry, sassafras, black cherry, persimmon, holly, black locust, blackgum, and red maple.

Age: Loblolly planted 2003. Various volunteer trees seeded in at that time or later.

Size: Medium, ready for first thinning

Quality: Good, a little too dense.

Trees/acre: Around 700 trees per acre

Growth Rate: excellent.

Recommendations:

Thin in 2020 to 80 BA. Understory burn soon after thinning, repeat every 4-5 years. Thin again +8 years 50 BA, to allow more diverse ground cover. Continue burn regime. Harvest around 2038.

Special notes:

Much of the land consists of fairly steep, north facing slope. Prescribed fire can back down the slope to wet SMZ.

Groves 2 – 6

These groves form one natural unit but are listed separately because they will be burned in different year to maintain the patch burn wildlife benefits.

Acres: 73 (Grove 2 – 26; Grove 3 – 8; Grove 4 – 7; Grove 5 – 20; Grove 6 – 12)

Forest Type: Loblolly pine planted 2003

Species Present: Loblolly & shortleaf pine, ailanthus, American sycamore, sweet gum, yellow poplar, eastern red cedar, hackberry, Virginia pine, mockernut hickory, white oak, chestnut oak, black oak, green ash, mulberry, sassafras, black cherry, persimmon, holly, black locust, black gum, and red maple.

Age: Loblolly planted 2003. Various volunteer trees seeded in at that time or later.

Size: Medium, ready for first thinning

Quality: Good, a little too dense.

Trees/acre: Around 700 trees per acre

Growth Rate: excellent.

Recommendations:

Thin in 2020 to 80 BA. Understory burn soon after thinning, repeat every 4-5 years. Thin again +8 years 50 BA, to allow more diverse ground cover. Continue burn regime. Harvest around 2038.

Special notes:

This grove is situated on high ground, that slopes into SMZ on all sides. It is divided by a gravel and dirt road. This will facilitate prescribed fire. The groves contain pollinator meadows, which should be burned more often than the surrounding loblolly in order to maintain and enhance pollinator habitat. As a substitute, will mow the meadow every two years and burn on same schedule as forest.

Groves 5 & 6 have significant infestations of invasive ailanthus, which require persistent management.

Grove 7

Acres: 8

Species Present: Loblolly & shortleaf pine, ailanthus, American sycamore, sweet gum, yellow poplar, eastern red cedar, hackberry, Virginia pine, mockernut hickory, white oak, chestnut oak, black oak, green ash, mulberry, sassafras, black cherry, persimmon, holly, black locust, black gum, and red maple.

Forest Type: Loblolly pine planted 2003

Age: Loblolly planted 2003. Various volunteer trees seeded in at that time or later.

Size: Medium, ready for first thinning

Quality: Good, a little too dense.

Trees/acre: Around 700 trees per acre

Growth Rate: excellent.

Recommendations:

Thin in 2020 to 80 BA. Thin again +8 years 50 BA, to allow more diverse ground cover. No fire regime on this grove. Harvest around 2038.

Special notes:

This grove is roughly triangular shaped, flat and damp. It is bordered by SMZ on one side, a forest road on another, but there are no natural or created barriers abutting the neighboring property. For this reason, we will not burn this grove. It can serve as a control case for other burned sections.

Grove 8

Acres: 14

Forest Type: Loblolly pine planted 2003

Species Present: Loblolly & shortleaf pine, ailanthus, American sycamore, sweet gum, yellow poplar, eastern red cedar, hackberry, Virginia pine, mockernut hickory, white oak, chestnut oak, black oak, green ash, mulberry, sassafras, black cherry, persimmon, holly, black locust, black gum, and red maple.

Age: Loblolly planted 2003. Various volunteer trees seeded in at that time or later.

Size: Medium, ready for first thinning

Quality: Good, a little too dense.

Trees/acre: Around 700 trees per acre

Growth Rate: excellent.

Recommendations:

Thin in 2020 to 80 BA. Understory burn soon after thinning, repeat every 4-5 years. Thin again +8 years 50 BA, to allow more diverse ground cover. Continue burn regime. Harvest around 2038.

Special notes:

This grove has about 300 yards of frontage on SR 623. It is mostly flat and wet.

Grove A – Cypress and tupelo

Acres: 7

Species Present: Loblolly, American sycamore, sweet gum, yellow poplar, eastern red cedar, hackberry, Virginia pine, holly, black locust, black gum, and red maple.

Age: Loblolly planted 2003. Various volunteer trees seeded in at that time or later.

Size: Medium, ready for harvest (see note)

Quality: Poor – the ground is not good for growing loblolly.

Trees/acre: Around 500 trees per acre

Growth Rate: medium

Recommendation:

Harvest in 2020, replant with cypress & water tupelo (see notes below)

Special notes:

This area drains the local road (SR 623) and is subject of periodic flood from the waters of Genito Creek. It heavily colonized by invasive multiflora rose. It does not support a good stand of pine, and I do not think it well-suited to loblolly and consider adding it to the SMZ. My plan is that when the rest of the tract is thinned, we will clear this section, burn the section and spray, as required. In spring 2021, we will plant bald cypress and tupelo, both better adapted to the soggy alluvial soil and this ecology will provide considerable water quality and wildlife benefits. Tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) is especially good for pollinators. We will plant about 450 to the acre, alternating rows of tupelo with cypress to provide diversity.

Grove B – SMZ

Acres: 50

Forest Type: Mixed hardwoods and pine.

Species Present:

Loblolly pine, ailanthus, American beech, American sycamore, sweet gum, yellow poplar, eastern red cedar, hackberry, Virginia pine, mockernut hickory, pin oak, swamp white oak, , green ash, mulberry, sassafras, black cherry, persimmon, holly, black locust, blackgum, box elder and red maple.

With an interesting variation, there are significant numbers of buckeye and catalpa, neither are native to this part of Virginia. I speculate that they were planted around some no longer extant homestead. I also noticed profusions of box elders, sometimes forming pure groves of short-lived trees.

Age: Mature trees 40-80 years old, some older and many younger. This is a mature uneven-aged ecology.

Size: Various sizes including significant saw timber. (10 to 18 inches in diameter)

Quality: Good to excellent

Trees/acre: Adequately stocked

Growth Rate: Good to excellent

Recommendations:

This parcel is in place to protect water quality and to provide wildlife corridors. We will periodically examine the SMZs for invasive species and treat as appropriate. Beyond that, this area will be generally left to natural processes, with interventions only in the case of disturbance, such as fire or particularly violent storms.

Special notes:

Most of the SMZ is along Genito Creek, a red bottomed waterway that meanders. In some places it has created natural levies. Genito Creek was originally the boundary of the property, and you can still see the former streambed, sometimes with flowing water. But the mainstream now runs several hundred yards into the Diamond Grove tract, promiscuously cutting into banks and disciplined only by infrastructure around the bridge over Diamond Grove road. Our property is also on both sides of Diamond Grove Road at the bridge, as the road was moved around 1960. The old road bed, about 100 yards from the current road, forms the property boundary.

Grove C Beauty zone

Acres: 2

Species Present: Loblolly & shortleaf pine, ailanthus, American sycamore, sweet gum, yellow poplar, eastern red cedar, hackberry, Virginia pine, mockernut hickory, white oak, chestnut oak, black oak, green ash, mulberry, sassafras, black cherry, persimmon, holly, black locust, black gum, and red maple.

Age: Some very large and old loblolly, oak and yellow popular probably 60-100 years old, but generally uneven aged stand.

Size: Various ages and sizes.

Quality: Good. Beautiful.

Trees/acre: Around 400 trees per acre

Growth Rate: mature

Recommendations:

Some old loblolly are probably reaching the end of their lives. If it seems appropriate to the loggers, we will remove a load of pine saw timber, facilitating the transition to a southern hardwood forest and retaining the attractive appearance along Diamond Grove Road.

Grove D – Oak & shortleaf

Acres: 2

Special notes:

I am converting a small area on top of the hill to the white oak and shortleaf pine ecology, likely a natural upland community in our part of Brunswick County. This is within Grove 6 and up against the start of a SMZ and holds a prominent place on a hilltop. I will be easily seen as an example of what can be done.

Grove E – Pollinator meadows

Acres: 2

Forest Type: Not forested. Early succession, grass and forbs

Species present: Little bluestem, splitbeard bluestem, purple top, bearded beggartick, lanceleaf corepsisis, Indian blanket, partridge pea, evening primrose, black eyes Susan, narrow sunflower, purple coneflower, eastern showy aster, rattlesnake master, Maximillian sunflower

Age: Established 2008, reestablished and replanted 2017

Size: N/a

Quality: excellent

Trees/acre: N/a

Growth Rate: excellent.

Recommendations:

Burn when we burn the surrounding woods. Mow once a year absent fire.

Wildlife Recommendations

Field Borders

Field borders are established along woodland edges and major drainages. Field borders create vegetative transition zones between cover types. Such zones are much more attractive to wildlife than the abrupt change that often occurs, for example, between field and forest. We have done this and will continue.

Daylighting

Daylighting consists of cutting most, not all, trees in a specified area to encourage and accelerate the growing and non-shade tolerant plants. Existing shrubs, vines and herbaceous (non-woody) plants should be left undisturbed to the extent possible. Woodland edges should be daylighted to a depth of 40 feet, recognizing that remaining trees will quickly reach out to shade the opening. Field borders established by daylighting have the advantage of taking no acreage from existing open land.

We are doing this with our thinning.

Borders need not completely rim every field or fringe every wood line. Yet, they should be employed to the greatest extent possible. Good field borders provide food, cover, and security. Perhaps equally important, they provide a most favorable “edge,” a critical component in the habitat chosen by most wildlife.

Open Fields (Pollinator habitat)

Probably the best practice to enhance open fields for wildlife is the establishment of field borders. These have been described.

Snags

Snags, dead or deteriorating trees, are an important habitat component in forests for wildlife. The availability of snags on forest lands affects the abundance, diversity and species richness of cavity nesting birds and mammals. Two to four snags per acre should be maintained in the forest. Such trees provide forage, cover, perches, and nesting sites for wildlife species such as raccoons, bats, flying squirrels, snakes, owls, woodpeckers, bluebirds (near open areas), and wrens, to name but a few. When snags are lacking in a forest, they can be created by girdling trees of poor quality or health.

Forest Openings

This area benefits from the development of forest openings to encourage the development of low growing plants. There are opening on all tracts, pollinator meadows.

Logging Roads

Soil erosion can be prevented through the careful location and maintenance of logging roads.

Broad base dips and drainage ditches should be placed 20 feet apart on steep slopes and 50 feet apart on medium slopes. Loading areas should be seeded in game food after harvest. When logging is complete, ruts and gullies should be filled and the road should be out-sloped slightly. Closing of roads to unauthorized traffic will prevent damage to newly sown grass or wildlife food.

Skid trails, haul roads, and log decks should be seeded with a mix of orchard grass and clover.

Prepared by: _John Matel_____________________

Forestry year in review 2019

Thoughts and experiences from another year in the woods -2019

Guardian or gardener

It just gets better. I have loved forests since before I can remember; this is my fifteenth year of having my own land & having my land, rather than just walking around on others, changed my outlook. Owing land lets me to make choices about the future of the land and it gives me the responsibility to make the right ones AND implement them on the land. It is easy to speculate about what would be good to do; it is another thing to do it. This is a lesson that comes from being responsible for land rather than just looking at it and demanding that others do something.

Preservation and Conservation

I read a book a while back called “Natural Rivals,” a joint life and times biography of Gifford Pinchot and John Muir. The conflict and cooperation of these two giants of environment is taken as the birth of the American environmental movement. The general idea is that Pinchot is the guy advocating wise use. He is the father of conservation. Muir is the spiritual ecologist, who sees transcendental value in nature. His legacy is preservation. Pinchot is identified with forestry and the multiple use National Forests. Muir is identified with National Parks. The two strains overlap in most places, but on the edges, there is serious disagreement about the place on humans in the natural community. The book says that the conflict was not felt as strongly by the men involved than we have subsequently read into it. I agree.

Most of the time, you need not choose and part of the genius of someone like Aldo Leopold was to melt the two together in a concept of land ethic, where you respect the land while regeneratively using some of what the land produces.

I try to live & practice a land ethic and not just read about it but reading about it is still important. I don’t need to rediscover what others have long since known. For example, I read Aldo Leopold’s “Sand Country Almanac” way back in 1972, but it was not until I had my own land that his wise words really made complete sense to me. It is the interaction over time that creates the meaning and the complexity the leads to the joy in serendipity. My study of ecology and forestry lets me make reasonable predictions about what will happen when I take actions. It would not be so much fun if I could predict exactly what would happen or if it was completely beyond me to make changes.

Living a land ethic

Leopold’s “land ethic” is both simple and profound. We all live in the natural world and should be mindful of the choices we make, both actions and inaction. Things we do that tend to improve the biotic communities on the land are good and those that harm them are bad.

The profound and ostensibly paradoxical part is that Leopold wrote that you cannot write a land ethic in a book. A land ethic must be written on the land. You leave your signature on the land you manage, and you learn from the land you are walking on. You learn from being involved. It is a melding of studying, thinking and doing. Together they are better than the sum of their parts.

Observe – participate – reflect – observe … It is circular and endless, but even when I write it in this order it is misleading, since they overlap and merge in the practice.

I made a pilgrimage to the Leopold Center this year to renew the ideas and maybe come up with a few new ones to help me write a land ethic on my land.

I am looking back over the last year and forward to the next. I wrote contemporaneous notes and commentary. I have used them as reference, used pictures and linked to some of them. I am surprised how much I sometimes forget. It demonstrates the usefulness of writing when memories are fresh.

Stewardship Forests

Freeman and Brodnax are now officially Stewardship Forests. DoF Adam Smith did the necessary paperwork. The program recognizes that we are managing to increase economic value, while protecting water and air quality, wildlife habitat, and natural beauty. This is how I want to do things anyway, treat my land according to a robust land ethic, but it is nice to be recognized. The official designation has a few concrete advantages. It is easier to participate in cost-share programs and it is required to get tax credits for riparian protection. This is a link to the Brodnax stewardship plan.

Landscape Management Plans

Virginia is a pioneer in the American Tree Farm System “Landscape Management Plan.” As President of the Virginia Tree Farm Foundation, I have been much involved with preparations for a study and pilot program that will be deployed in Virginia east of the Blue Ridge, and I will be involved with the implementation. I hope to be the first tree farm to sign onto a landscape management plan in Virginia, lead by example. More background on land management plans is here.

Landscape management plans (LMP) by the American Tree Farm System looks at this bigger picture and create plans by which landowners can know what to do with their land to make sure it is in harmony with the environment in general and with land of other owners in particular. This is the part I like the best. I can also appreciate the practical aspects of making it easier for landowners to plan and for the Tree Farm to update. LMPs have been deployed successfully in parts of Florida & Alabama. We hope to be statewide in Virginia within a couple years.

Changing emphasis for the American Tree Farm System

I observe that tree farm is migrating a little away from tree farming, and I want to help push in this direction in my leadership capacity in Virginia. The American Tree Farm System (ATFS) was founded in 1941. America and the world were very different in 1941. We were worried about running out of wood and tree farms would address that. We also had confidence in a more mechanical view of nature. Trees were a crop like other crops. Sure, there was a longer time between planting and harvest, but the principle of the farm applied. That is why they called it tree farming.

We have learned a lot more about ecology and natural relationships since then. I often repeat the phrase that trees are more than wood and forests are more than trees. I don’t think this would have had much resonance with tree farmers in 1941. Their reality was different. People like me can be much more inclusive in our view of the ecology because we stand on the shoulders of those who went before us. I am grateful for the boost, but we have to think differently now, not contradicting the old guys, but building on their legacy.

Back in the old days, they needed to be very efficient in the attainment of one goal – produce more wood and forest products. We still need to be efficient. We still need to produce wood & forest products. We still need to make profit, since that is the cost of survival, but our goals have expanded to include tangible ecological services – protection of water, soil, beauty and habitat – as well as the intangible “doing the right thing” in nature and in the communities, human and natural, that depend on the health of the forest.

Let me get my head out of that cloud and move onto more practical interactions.

Cutting paths

I got a Stihl cutter a few years back, but it became really useful this year when I got a three-pronged blade that can cut through brush, brambles and grass with equal alacrity. I am not sure if it came just in time or if it was an example of the tool determining the task, but I put it to work for hundreds of hours this year. My first task was to cut paths for the prescribed burn on Freeman, both to allow for more efficient fire-starting and to provide breaks to slow the fires so that they do not get too hot. I describe this a more below.

I spent more total hours with the cutter on Brodnax, however. I was looking for the longleaf planted in 2016. My experience on Freeman was that brambles and weed competition had killed many. My other concern was that these longleaf were planted in early April, too late in the season. W/o the cutter, I could not get into the tract because of the brush and brambles. With the cutter, I could make paths and then cut around the longleaf that I found. The cutter is especially good with brambles, nearly impervious to other methods. I can raise the tool and then bring it down on the brambles and they are effectively grubbed up. More on my plans for this tract below.

Some more information on this cutter at this link.

Brodnax

This is the link to the Brodnax Stewardship Plan

Dormant season burning

We started the year with a winter burn in early February. In partnership with NRCS and the Virginia Department of Forestry. We all need friends and good advice. Our Virginia forestry folks and the Federal employees at NRCS are perfect partners. We have mapped out a regime of patch burning on our land in Brodnax. This was the second of three planned patch burns and it was as perfect as we can hope in this world. We burned up the hill, against the wind and then backed the fire down to the creek. The fire burned the brush but left the soil intact. The brush was dry, but the soil was damp – as I said, perfect. The fire pruned the big trees but did not kill any of the large pines.

Prescribed fire, not controlled fire

It is exciting to watch and sometimes frightening. We call it a prescribed fire and not a “controlled fire” because fire is never fully controlled. Our forest includes a lot of holly in the understory. Holly keeps its leaves all winter and I thought the green leaves would resist the fire, quite the opposite. The fire crept along the ground most of the time but virtually exploded when it hit a holly bush. They burn fast and hot, but it lasts only a short time and burns only the leaves. Our fire was not hot enough and did not persist long enough to burn stems, although it did top-kill most of the hardwood stems. When I inspected in the spring, I was delighted to see little oak trees coming up from the roots.

I attended a three-day seminar in fire in oak forests, held at State College, Pennsylvania. One of the speakers commented that fire is like an animal – maybe a keystone predator (my words) – and lamented that fire in upland oak forests is essentially extinct. Its extirpation is a blow to forest ecology and bringing it back will be useful. We are bringing it back.

Fire is a primal human tool, part of being human. Animals do many things that humans do. Chimps make and use simple tools. Birds communicate. Bees create synthetic materials to build impressive hives, and termites create cathedrals in clay, compete with air conditioning. Only humans control fire, even if control is never complete. Watching “your” fire climb your hills into your trees is a unique experience. The fire often passes quickly, but it seems to hold time still. A great experience.

Plantations of Brodnax

Also, on Brodnax, I worked with my longleaf and loblolly pine, both planted in 2016. The longleaf are struggling. I think they were planted too late in the season. The crew planted them when they planted the loblolly. Loblolly are more forgiving. It is best to plant longleaf in winter, when it is cold and usually wet. When they planted these, it was in April, and planting was followed by a dry spell. I think the logic was that they would be okay because they were containerized. I have been looking for the little pines and not found as many as I would have liked. We sprayed and burned in 2018. This should have cleared the ground for them, and it did, but incompletely. My options are to replant longleaf or put loblolly. I am choosing a third option, maybe. There are some large white oaks at the edge of the plantation. I will see if we get oak regeneration on nearby and if we do, I will nurture those oaks, leaving an oak-pine forest. When the oaks get a little taller, they will resist the fires too. It can be magnificent. I will never see it in fact, but I love the idea.

White oak initiative

Speaking of oaks, I am giving special treatment to existing root sprouts & sapling oaks on other parts of the property. The Brodnax place seems a good place for oaks, judging by common presence as volunteers. The cool fires seem to be good for the oaks and I found a bunch coming up after the burn. I identified some oak patches and went through to knock down the gum, poplar and sycamore. Thinking again of Aldo Leopold’s “Axe in Hand,” which I think of very often when I am moving in the woods, I am making what I hope are thoughtful choices about what will be on the land after I am gone. I thought of planting some oaks, and still may to get some genetic diversity, but I think the stand can develop well if I just nurture some of what is there.

Other oaks too

I gathered a couple hundred acorns from a magnificent burr oak near the Capitol. I planted them in the blank places in the Brodnax longleaf are where the longleaf failed to survive. Unfortunately, there was significant blank space. We will see how this works.

We also planted 30 acres in loblolly. I have been in there with my cutter, making paths so that I can see. We strayed in 2017, but there is a lot of hardwood competition, mostly gum & poplar. Poplar are not much affected by Arsenal, which was the big component of the spray used on pines. I have a wonderful new cutting head for my trimmer. I have been making paths into the plantation and will continue to do that, taking down the recalcitrant popular and gum. Taking into account hardwood competition, the loblolly are doing well expect in a few patches where they were overwhelmed by hardwood competition and/or bramble. These I can whack back with my cutting tool. I ordered a thousand pollen-controlled loblolly from ArborGen. I will plant them in February in these patches and see if they do better. They are containerized, so most should survive. If they do as well as advertised, they should catch up with the ones planted a few years ago, and if they succeed, I will plant those sorts in future. Genetics matter. I am just not sure how much on the ground on my land.

Freeman

Freeman has been my big focus this year and will be next year too. We thinned the pine forests on Freeman last year to 50 basal area and made ¼ acre clearings in each acre. Last winter we planted 3,500 longleaf in some of the gaps, along with 200 bald cypress in any place where my feet were wet. We got the bald cypress from ArborGen and I think they come from Louisiana. We bought the longleaf from Bodenhamer Farms in North Carolina, so my trees are not “native” Virginians. They are transplants like I am, but I figure the trees don’t recognize the boundary set up by the English kings. This year, we will get another 8-9,000 longleaf.

We had a small problem with turpentine beetles. They killed a few trees. Virginia DoF came by and recommended Bifenthrin. I sprayed the beetle trees and those around. We then burned under them and I think we got the beetles.

The fire did not get very hot, in fact it did not burn much at all. We backed the fire down to the creek and did a good job on the grass, but it just fizzled out in the darker, damper woods – a practical lesson in fire behavior. And I think we got the bugs. Turpentine beetles are more a nuisance than threat. Even if I did nothing at all, they would probably have killed only a few trees, but since I had the time and inclination, it was worth it get it done.

Longleaf pine in Virginia

I am not the only guy in Virginia working to restore longleaf pine ecologies in the Commonwealth. Lots of people are working on it and there is a lot of passion associated with longleaf. The Longleaf Alliance held its first in Virginia “Longleaf Academy,” and I was flattered to get a special invitation to participate. I attended a longleaf academy in Georgia, so much of this was familiar, but it was Virginia and so more to our specifics. I also was glad for the chance to meet and/or renew relationships with Virginians sharing the vision.

Bill Owens is the leading longleaf landowner in Virginia. He has planted hundreds of acres of longleaf in Sussex County and had decided to deed some of it over to the Nature Conservancy. I attended the hand-over ceremony, got the tour and attended the reception at the Petersburg Country Club. Guests included other landowners like me, officials from Virginia Department of Forestry, U.S. Forest Service, NRCS and – of course – TNC. The guest list of participants says a lot about how forest and land management is a community affair. Nobody is a island.

Succession and complex communities on Freeman

Let me dive a little deeper into what is happening on Freeman. I was spending a lot of time there this year, observed more than before and got a chance to think about what was going on

Working on the land is all about relationships – relationship with the ecology, relationships with the people who work with you and relationships with yourself. What I do or what I cause to be done seems to manage the land. What is really happening is that I am moving around some of the big and most obvious parts, but what is going on around them is often more interesting, and it is a joy to discover the interactive and growing parts.

Wetlands and wildflowers

An interesting unintended but not unpleasant consequence of thinning and making clearings was to create wetlands, or at least damp ones, as the thinner or absent trees do not suck up as much of the rainfall. We cleared around four acres next to our 2012 longleaf plantation with the intention of planting this in longleaf, part of the overall longleaf restoration plan in cooperation with NRCS. The kids planted the longleaf last year. Between this new longleaf and the old ones, however, is a large area of damp land. I planted fifty bald cypresses and “discovered” a couple dozen that were planted in 2012. I knew they had been planted, but I did not know that they had survived, as they were hidden and shaded by the 22-year old loblolly. Now in the open, they may grow robustly. I went around with my cutter to give them more space, as the newly available sunlight caused lots of things beside them to grow. I am fond of these marshy areas.

Succession and the swerve

There are a lot more than bald cypress, however. If you create the conditions, they will come and all sorts of wildflowers, grasses and forbs have sprung up. The seeds and some of the roots were in the soil when conditions were less auspicious and ready to go when the vista opened. I cannot identify all the sorts of flowers. In late summer, however, the wet strip was dominated by joe-pye weed, loved by pollinators and beautiful to see. On the verge and within the pine plantations, I planted Southeast wildflower mix. I even planted some less common components of the southeastern pine forests, like prickly pear & rattlesnake master. I planted in patches, where I could provide better environments, keep an eye on progress and not lose the seeds by casting them too broadly or thinly. I hope and believe that they will spread by seed, rhizomes and runners. That is my plan at least, which may flexibly and opportunistically be accomplished with help of the relationships with the land and the biotic communities.

The longleaf patch – the crucible of the future forest

My 2012 longleaf patch is where I have spent much of my time on the farms. This has been true ever since it was planted. It is big enough to be significant, but small enough (at about five acres) that my efforts make an easily seen difference. I think of it in terms of a crucible. I learned practical skills, could experiment with longleaf, with fire and with being a conservationist on this small patch. I can extrapolate to the larger spaces.

Longleaf pines are more diverse genetically compared to loblolly. If you plant loblolly, they are all about the same height at the same age and conditions.

Some people think that this extreme variation among longleaf is an adaptation to fire. Longleaf are fire adapted, but not all ages are the same. They will usually die if the terminal bud is destroyed and are most vulnerable when they are about 6 feet high. The flames usually pass over the smaller ones and do not reach the terminal buds on the taller ones, so having various sizes means that some always survive. I don’t know that pine trees do all that much planning, but it could be true, although not by design.

All this variation and the need for fire makes longleaf harder to grow than Loblolly. You just do not know what to expect. But my longleaf are an experiment anyway, and lots of people are interested in the results. I get lots of support from NRCS and Virginia Department of Forestry. Longleaf once dominated Virginia roughly south of the James River and east of the piedmont, but they have not been growing in the Virginia piedmont for more than 100 years. My trees are not native Virginians. They are from North Carolina. Not sure how they will do, but I doubt that the trees recognize state borders.

Landscape painted by fire

In “nature” open pinelands are maintained by fire and this is ultimately how I want to manage mine. But fire is a dangerous tool. I am not competent to use it as much as I think I should. In the meantime, I depend on chemical and mechanical tools.

I spent many days cutting with my brush tool and accomplished, making paths for us to more easily light and control the fires. In September, I had the forest north of the lines professionally sprayed. They used a helicopter to get it done. I will see how it differs on either side after recovery from the fires.

Fire and planting

In December we burned under the loblolly on Freeman and in the clearings. We also burned the longleaf patch. The fire top killed brambles, but did not burn them away, so it as hard going planting in some of the patches.

Burning is good, but it always scares me. I inspected my longleaf most carefully. Some of the needles are singed and will fall off. I checked for the buds on some of the lower branches, figuring that that was most likely to be killed and that higher ones would be better. I found that middle was still green and will be growing, so I assume the tops are good.

Longleaf is fire adapted. The needles singe, but when they heat up they release humidity that protects the terminal buds. The buds are what count. If the buds are alive, the tree will grow again.

Chrissy and I planted 3350 longleaf seedlings the week of December 9. It was a lot of effort but worth it because we got to handle and touch all the little trees. This adds to the 3350 we planted last season, the maybe 4000 in the longleaf patch and we will finish up with the kids planting a few thousand more early 2020. We will not be 100% done, however. I expect to be planting longleaf to fill in for the next few years. When we are done, we will not have a truly uneven aged stand, but it will have some variation of age class.

Planting trees with the dibble stick in indeed very hard work. As I write this, I feel the pain in my hands with each keystroke. The pain will soon pass, but the memory will abide. It was immensely gratifying to do the planting and to look back at the clearing with the little longleaf and that Chrissy was doing it with me added to the pleasure.

Why do it?

I could hire a crew to plant, and I think it would cost me less than we spent in gas and hotels to do it ourselves. But that would miss the point of owning forest land. I don’t want a consultant because I want to do it myself. I don’t want to hire others to plant my trees, because I want to do it and I want Chrissy and the kids to be involved. The meaning and the joy come not from the result but from the process. It is cliché to say that it is the journey and not the destination, but it is true in this case. Sure, I will hire crews to do a lot of the hard work and I know that someday, sooner than I want, I will be unable to do the hard, physical work of burning, cutting and planting. But until that day, I want to experience to the fullest. When I look at my groves of longleaf, I will know that I am connected to them, not just by signing my name at the bottom of a contract, but by putting my signature on the land.

Diamond Grove

The 178 acres at Diamond Grove was my first forest. I knew little about forestry in Virginia and pretty much nothing about buying rural land. I may have paid a little more than I should have, but not that much. I was lucky. I love this land, but this is the one I visit least these days. On some visit to the farms, I do not visit at all. This is because there was nothing for me to do besides look. The pines were established and growing well, but not yet ready to thin. I sometimes went and fought the invasive and the vines, but this work was mostly optional. Since we planned to thin in the next couple of years, knocking down the vines did not make much sense. It was like vacuuming the carpet before you pull it up. This situation will change early next year.

Thinning

Our plan is to thin this winter (January or February 2020) to about 100 basal area. This is standard for a first thinning. Kirk McAden’s company will do the thinning. His forester suggested 100 BA or even 110. I will go with 100. If we thinned to much less, the trees would not self-prune and the competition would be stronger. For the next thinning, I will go with 50 BA, as on Freeman, but that is a while in the future.

Wet roots – bald cypress and tupelo

I am going to completely clear about 5 acres near Genito Creek. This is damp land and I expect when the trees are gone it will become positively wet. Pines do not grow well on this land. What grows well is invasive multiflora rose. I have been fighting this multiflora rose battle for more than 10 years and I am losing the fight, so I mean to change the rules of the game. We can do good site preparation, burn and then plant bald cypress. I may mix in a few black tupelos. These species will thrive on the damp and do well even if it floods, as it has sometimes done. I visited a forest like this in the Congaree National Park in South Carolina. If we project global warming, these trees will be just where they belong by the time they mature. If conditions do not change, they will still be okay. Tupelo and bald cypress can grow in this part of Virginia. I have seen healthy bald cypress forests in Ohio and individual trees thriving as far north as Wisconsin. Tupelo grow naturally, if not commonly all the way north in Maine. Tupelos are a wonderful part of the ecology. Birds love the fruit and bees love the flowers. Maybe somebody can harvest these trees way in the future, but for my lifetime I figure I will just think of it as SMZ.

Summing

2019 is almost done. All I will do this year yet is carve a few paths through brambles for that the kids can more easily plant longleaf in January of next year. 2019 has been a good year in the woods, best year ever. 2020 will be better yet.

Nature's Mutiny

This was a disappointing book. I suppose it would have been good in its own right, but it was not really about the subject promised.

It started off right. The author claimed he was going to explore changes in Europe the last time we experienced rapid climate change. But he quickly went sideways with a lot of talk about philosophy & religion only tangentially related to the change in climate. To simplify only a little, he essentially says this happened and that happened and that happened, and BTW it might be related to climate change.

I finished the book because I was listening to the audio book while I was planting trees and had nothing else to do. I think doubt I would have finished otherwise. In other words, if you’ve got nothing better to do, read this book, but I cannot generally recommend it.

Are you proud of your ethnic heritage? My Story Worth.

Odd question and I had to think about it for a little while, but no – I am not proud of my ethnic heritage. Let me explain.

Germans

My mother’s family thought they were German. I say “thought” because my DNA indicates that they were not very German at all. Roughly ¾ of my DNA ancestry is Polish and I am more Scandinavian than German, according to the DNA. Since only half my ancestry could have come from my father, my mother’s DNA has a lot of ‘splaining to do. (If it was my father’s DNA difference, it might cause more of a scandal, ex-post-facto) Of course, DNA is not closely related to real nationality. My great grandparents on my mother’s side came from Germany, spoke German, drank beer like Germans and ate sausages like Germans, so that is my heritage on that side.

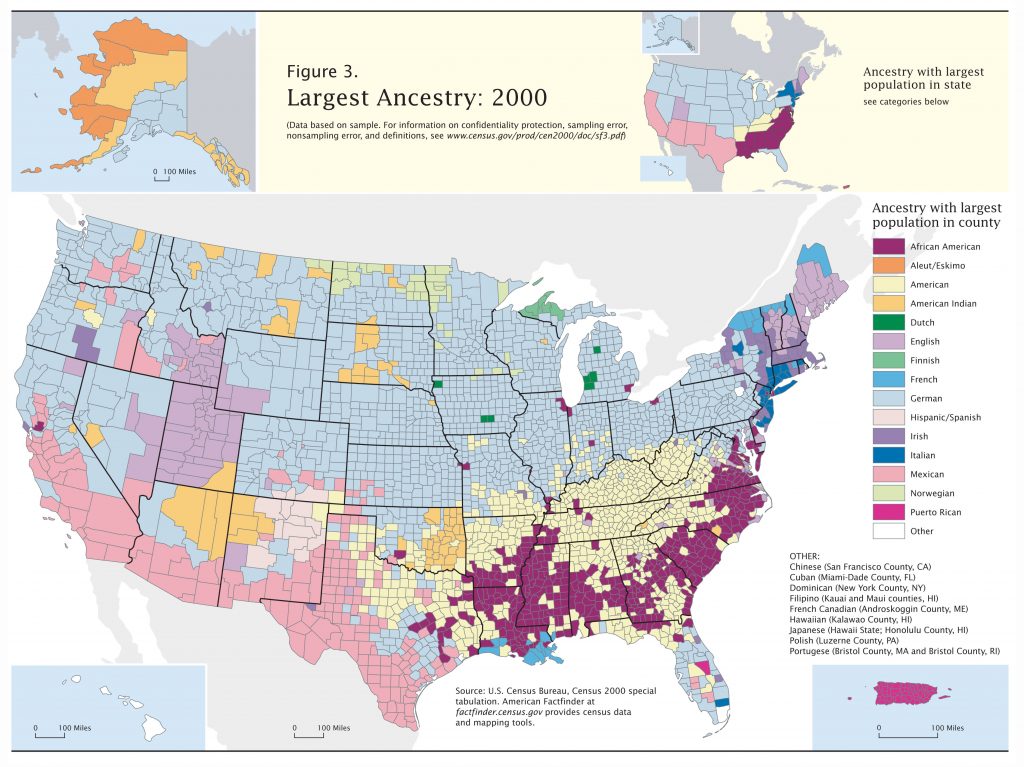

America is a very much a German influenced place. Germans around 1900 were like Hispanics today, only a greater percentage of the population. When Teddy Roosevelt complained about “hyphenated Americans,” he was talking about Germans. The 2000 census counted 58 million German Americans. Hispanics are assimilating like Germans did, BTW. States and local governments made rules against the use of the German language and native Americans feared Germans would take over the country. German immigrants and their children were majorities in many places (see the map). America absorbed all of that, and in the process lots of German things were modified to become American – apple pie, kindergarten, hamburgers, hot dogs, research universities, beer gardens …

How many Poles…?

My father’s family thought they were Polish, and the DNA confirms a lot of that. My grandfather was born in the Russian Empire and people ignorant of history might think he was Russian, but the empire thing explains his “true” nationality, just as a Indian living in the British Empire was not English. Similarly, my grandmother’s family was from Galicia in the Austrian Empire. She was not Austrian. They were Polish speakers and Polish ethnics living respectively in two of the three countries that held Poland in a colonial relationship in the 123 years from 1795 when Poland ceased to exist until 1918 when Poland was reborn.

Ethnicity is bunk

Ethnicity is complicated and ephemeral. We think about it reaching way into the past, but this is inaccurate. Whatever you think your ancestors were, you are wrong. Cultures have echoes but they must be recreated with each generation. There is an illusion of continuity. It really does not matter what you were, or thought you were. The past is a foreign country for ALL of us and it all is the common heritage of humanity It would be hard to find a contemporary American more different from me today than my great grandfather would have been.

That is why I am not proud of my ethnicity. I didn’t do anything to build it and it affects me only in kind of a sentimental way.

My own culture was cobbled together from disparate strands.

The Upper Midwest was like Mitteleuropa

I think basically that I am “ethnically” Wisconsin, but not Wisconsin of today, the one I grew up with. It was an amalgam of immigrants and old Yankees. We talked a lot about dairy in Wisconsin. That came from immigrants from Central Europe and Scandinavia, but also from immigrants from New England and New York state. They gave us our cheddar, but we invented Colby, which is better. Wisconsin had superb sausages. Our beer sucked when I was young, but that we before the craft brewing renaissance. I learned to love the rolling hills of the glaciated land, all the little lakes and the big one, Lake Michigan. And I learned to love the Green Bay Packers. These things are still “home.” Should I be proud of this? It is part of me, but that is what it is. This ethnicity is much stronger than anything my genetic ancestors were in centuries past.

Greeks and Latins

A part of my heritage that I am somewhat proud about is my classical education. This is a completely artificial addition to my “culture,” which is precisely why I can take some pride in it. If I could trace my ancestry back to AD 1, my ancestors would be those barbarians that the civilized folks fought, feared, conquered and enslaved. But the civilized folks wrote literature and developed philosophy and I claim them as my forebearers as my common heritage of humanity.

America swallows ethnicity

The biggest part of my heritage is American, just American. None of my ancestors were here for the first part of the American experiment. I suppose I can claim kinship with Kosciusko, Pulaski and Von Steuben, who helped America win its independence, but that is a reach. But I absorbed the experience of the Founding Fathers, the westward expansion, the Civil War and the industrial expansion. My folks got here in time to work in the factories that gave us modern America and fight in the World Wars that kept us free. My German family members fought with equal enthusiasm against their erstwhile German relatives.

The great thing about being American is that we can forget or recall our ethnicity at our option. I like lots of the thing Germans and Poles contributed to America, but most of the things I like are from some other sources. I like bratwurst, but generally prefer pizza and I know both those things are American.

I love cultural appropriation

In fact, most things I like are mixed and matched. Americans pick what they like best from around the world. You don’t have to be from a place or of a people to take what you think best. All good cultures are glad to share and all great cultures are promiscuous “borrowers.”

So, am I proud of my ethnic heritage? I am proud to be an American and grateful that my ancestors made the choice to come and join America.

My Polish cousin

I met one of my cousins when I was in Poland. His name was Henrick Matel. His father was my grandfather’s brother. His father went to France to dig coal, while my grandfather came to America, where he worked in a junkyard. Neither had an auspicious start. I think Henrick kinda looked like me, but lots of people in Poland look like me. All that DNA gives you a distinctive look. Our families had diverged only one generation ago in his case, and two in mine, yet we were not similar besides in having blue eyes and not much hair. He was maybe twenty years older than I was, i.e. he was a little younger than I am now. But he was old and infirm. Living in communist Poland did that to people. And I was American. He commented that I was so upbeat and optimistic, that I smiled easily. He said, a bit ruefully, that I had a lot more to be happy about, and he was right. My grandfather chose to be American. He never was materially successful in his new country. He worked all his life in crappy jobs, but he was a free man.

A heritage of freedom

Freedom is my ethnic heritage because I am American. I am proud of my country. I am not proud of my ethnicity that I did nothing to earn, but I am profoundly grateful that grandpa made the right move.

My first picture is my mix of heritage. Espen bought me the German style hat and the Christmas tree is a German tradition. We got the creche in Poland. On the other hand, I have my cowboy style belt buckle and in the background are posters from Chicago and from our American National Parks. The map shows how widespread Germans were/are. They are the light blue.