Sky islands are communities of plants & animals in places like Arizona characteristic of more northern ecologies. Altitude substitutes for latitude. They are remnant populations, surviving from a time when the earth was much cooler during the most recent ice age. As the earth started to warm about 10,000 years ago, these cooler-adapted communities moved up the mountains. They are like islands because they are surrounded by scrub or desert. That makes them precious and vulnerable, since they are unconnected to other islands or to the larger populations of their similar species, i.e. from seed/genetic banks to regenerate if a population was extirpated locally. It also makes them extremely interesting, since you can essentially go through biomes from hot desert to something like Canada by walking up hill and they provide lessons for adaption when climates change.

We came to the sky island at Ramsey Canyon to see Apache pine, pictured above. I learned that Apache pine have an ecology kind of like longleaf and kind of like ponderosa. Since I love both those species, I wanted to get to know these too. Apache pine are mostly present in Mexico’s Sierra Madre. They extend into the USA in parts of New Mexico and Arizona on patches like Ramsey Canyon. The Nature Conservancy owns a the preserve at Ramsey Canyon. I asked if I could talk to the steward of the place, and Eric Anderson was good enough to spend the morning with us, explaining the unique ecology of this part of Arizona. Eric and I are pictured below.

Ramsey Canyon sits at the nexus of four disparate biomes. To the north are the Rockies; south are the Sierra Madre; west is the Sonoran Desert and east is the high Chihuahua Desert. All of these influence the plant and animal communities, and you find species associating in ways like no place else. For example, Eric showed us agave cactus next to Apache pine, not far from Douglas fir and partly in the shade of massive sycamores.

You can see some of this above and below. The Douglas fir surprised me. There were some really big ones. I associate Douglas fir with the rain forests of the Pacific Northwest. I did not expect to find them thriving so far south and near such dry deserts.

Most of the timber from the region was cut in the late 19th century, with the wood used for houses, mines and fuel in what were then fast-growing places like Tombstone and Bisbee, at the time among the fastest growing cities in the USA. Eric thinks that accessible forests were was mostly clear cut and the wood hauled away. Forests regenerated, but they were very different from those they displaced. The open and park-like coniferous forests were replaced by thick brushy forests of scrub oak. What these forests mostly produced was fuel for disastrous fires. When conifers did grow back, they also came in thick, what foresters call “dog hair” woods. These provide little space for the food that supports wildlife, and, like the scrub, they burn very hot.

On a tangent, Eric told us that the oak trees do not drop their leaves in autumn. They hold them throughout the winter and drop them in spring, before the hot and dry period in April and May. Those are the hottest two months. After that, the rains arrive and the wetter and cloudier weather cools the hills.

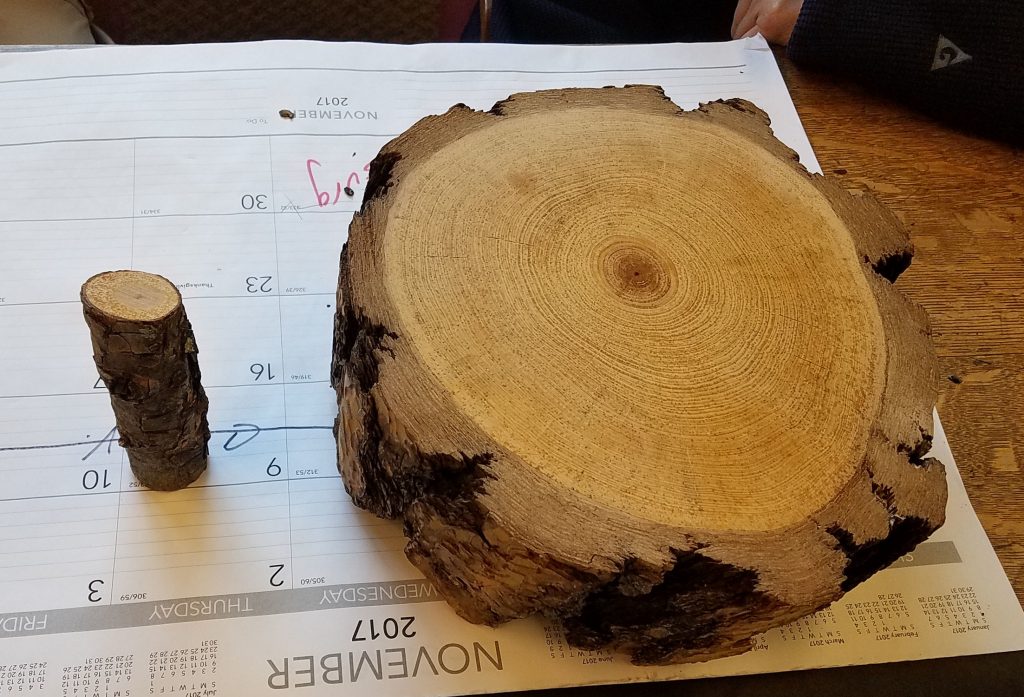

Fire was a key component of the pine forests. It burned through every 7-10 years, but those fires were low intensity. It knocked out the scrub but big trees were largely immune. The new fire regime featured less frequent but hotter fires that destroyed much of the standing forest and burned to the bare earth. It was a terrible cycle and we are still suffering. You can see a cross section of an Apache pine in the picture above. The thick bark is almost immune to low intensity fire. The two cuts you see below are about the same age. The one grew in an open forest; they other was part of a “dog hair” forest.

TNC wanted to reestablish natural rhythms, but could not used fire as much as the the natural ecology would indicate because there is too much chance of it getting away into nearby inhabited places. Another complication is that Ramsey Canyon is surrounded by wilderness areas. You would think that wilderness areas would be more “natural,” but you would be wrong. These areas were also impacted by the logging and mining of past, but now they are frozen in that state. They also grew back in the scrub and “dog hair” manner. They are full of fuel and are liable to burn in that disastrous way I mentioned above. Because they are officially called wilderness, they are subject to various restrictions and cannot be managed to reduce fuel and fire risk in ways that would be applied elsewhere.

On the TNC land, they have thinned down the scrub oak on the north facing slopes and they hauled away the cutting. This is not as good as thinning followed by prescribed fire, but it as close as they can do under the current restraints. Some beneficial results are already clear. We saw regeneration of Apache and Chihuahuan pine, seedlings and young trees. The young Apache pine look a lot like longleaf in their grass and bottle brush stages.

There was a nice section of almost pure Apache pine. We could see carbon on the trunks and speculated that this area was fortunate to have a few low intensity fires pass through. It is amazing what comes back when you reestablish some of the natural factors. You can see the thinned brush above and below. Eric says that before the thinning, it was almost impossible to walk through the brush. Since the thinning, he has noticed that raptors like hawks have come to the area and more wildlife in general is present.

Eric shared a poignant story about the guys who do the thinning. They are convicts from the local prison. It is sought after work for them and Eric says that they are usually hard-working and thoughtful men, but with the big problem is that they cannot stay out of trouble. He says that when they get out on parole, they often come by with their wives or mothers to show them the work. They are proud of the work they did and the restoration they helped encourage. Eric stays in touch with some of them, but it is hard for them to stay on the straight and narrow. When they get out, they often fall in with the same sorts of people and lifestyles that caused them the trouble in the first place.

TNC is doing wonderful work to protect and regenerate these precious sky islands, and they do such excellent work wherever they are. I love what they are have done and are doing with longleaf. Theirs is the perfect combination of doing-learning-adapting and doing again. I have visited TNC preserves all over the country. Seeing their work and hearing about it from the people doing it is a great privilege.

Below is a link to more information about Ramsey Canyon.