My father was born on this date in 1921. I don’t really know much about him and some of what I think I know is probably wrong. We didn’t have much contact with his side of the family. Both his parents died before I was born. He and his fraternal brother Joe were the youngest. They were born twenty-two years after their oldest sister, Helen.

On the left are my grandparents.

I was named after my father, so I am technically John Matel, Jr. John Matel Senior was born in Duluth, Minnesota. His father, Anton, had come over from Poland a few years before. I don’t know when. His mother, Anastasia, was of Polish ancestry too, but she was born in Buffalo, NY. My father never told me much more than that, although I understand that her family was from Galicia in the Carpathian Mountains.

I found out later that my grandfather’s family was from what is now eastern Poland: Suwalki and Mazowieckie. I learned this from a cousin called Henrick Matel who found me in Poland. His father was my grandfather’s brother. His father & another brother went to France to work in coal mines there. My grandfather made a wiser choice and went to America. Henrick didn’t know much else. His father had been killed in a train accident when he was only eleven. Henrick unwisely returned to Poland after WWII, believing the communist promises that things would be good there. Young men make bad choices.

Henrick lamented that the Polish side of the family were a bunch of drunks. Things didn’t change much in America. Now you know as much about my father’s prehistory as I do and I suspect a little more than he did.

My father talked about growing up in the depression. He kept some of the frugal habits from those times. He used bacon grease as butter, for example and would get really upset if we threw out any food. His childhood home was small and crowded. It was on 4th Street. I went up there to see it. Of course, by then it was different. It was in a yuppified neighborhood and a small home for a single couple. My father’s home housed eight. Their toilet was in the basement, which has a dirt floor back then. He told a funny story about his youth. The family went to see “Frankenstein” and it scared my future father. His brothers set up a dummy in the basement and the made it sit up when little Johnny went down to use the toilet. He said he no longer needed to use the toilet.

He got a job with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and was stationed near Superior, WI. He planted trees and cut trails. It gave him a lasting appreciation for forestry, which I think he passed to me. How else can you explain a city boy so attracted to the woods? Some of it is myth, or just a feeling, but whenever I look at the groves of trees planted by the CCC I think of him. They are mature forests now, but in the Dust Bowl years they were pioneers.

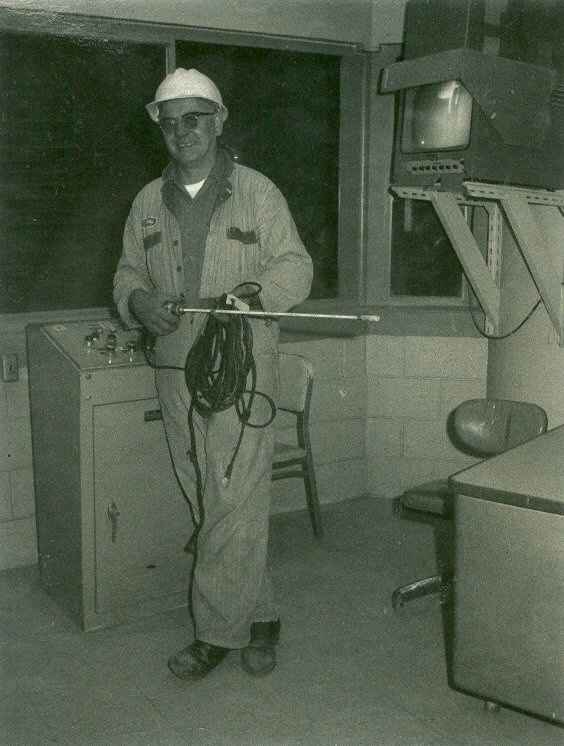

After getting out of the CCC, my father got a job at Medusa Cement, where he stayed his whole working life, except for the time he was in the Army Air Corps. He was drafted into the Army soon after Pearl Harbor. He would never tell me much about that part of his life. I know he got seven battle stars, so was a participant in all the big action of the war in Europe. Of course, he didn’t really have to be there for all of them. Anywhere the planes went, he officially went. He landed at Normandy a few days after D-day. According to what he told me, the only time he actually got near the Germans was during the battle of the bulge, closer than he wanted. He got a Purple Heart.

They had a point system for discharge from the military. My father had a lot of points because of those battle stars & Purple Heart mentioned above, so he was among the first U.S. soldiers discharged. He always expressed a special fondness for Chicago, where he was discharged. Since he was among the first to come home after the victory in Europe, people were eager to welcome him and buy him drinks.

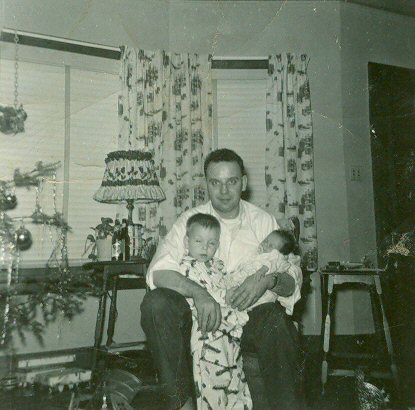

I am embarrassed to say that I don’t know exactly when he married my mother, but it was soon after the war. They told me that it took nine years before I was born. I was born in 1955, so counting back we get 1946.

On the left are my uncle Joe (blond), Ted (tall) and my father.

Our house in Milwaukee was full of artifact of my father’s work. He and my mother’s father built the boiler, constructed the steps in the back and built the retaining wall, for example. All these things worked, but they were odd. The boiler threw most of the heat out through the sides. That meant that the basement was very warm – the rest of the house not so much. The steps were all uneven. The wall leaned and the drainage holes were lined with beer cans cut out on both ends. The evident surplus of beer cans explained much of the other things.

During my childhood, my father mostly worked. That’s what I recall. It was the time when they were building the Interstate freeways and there was a big demand for cement. He regularly worked twelve hour shifts and was tired when he came home. He drank a lot of beer, at first Schlitz, later Pabst and then Budweiser, but he never missed a day of work because of it, or for any other reason. I don’t remember him ever taking a sick day. Maybe he just denied sickness because he hated doctors. He went to the doctor only once from the time he got his discharge physical out of the army in 1945 until the time he died more than fifty years later. On that occasion, he had a cyst removed from his stomach. The doctor forgot to sew it up. After that, he said that the medical profession had their chance and he was not going to give them another. When the doctors finally got their second look at him, the day he died, they couldn’t believe my sister when she told them that he didn’t take any medication besides Budweiser.

I really didn’t get to know my father until my mother died in 1972. He was grieving too, but he tried to make it easier for my sister and me. He tried to cook, but wasn’t very good at it. But my father was nothing if not stubborn. He ate what he cooked and made us eat it too. I remember watching some bread bake in the toaster oven. The old man asked if I thought it was ready. Just at that point it burst into flames.

My father dropped out of HS in the tenth grade, but he made sure I went to college. He also got me a job at the cement company, where I got to work those twelve hour overtime shifts and make the big bucks. At one point, they assigned me to unloading hopper cars. I worked from noon to midnight, which was great. I could sleep late and then meet my friends at the bars at midnight. At the job, I got to lift very heavy tools and smack things with sledge hammers (something young men like) but in between the hard work I got time to just hang around by the river and wait for the cars to empty (something else young men like). Then I got to ride the cars to the end of the dock, applying the brakes and jumping off just before the rammed into the car in front. I mentioned to my father that I thought this was fun. The next day, he made sure the boss gave me the midnight till noon shift, which didn’t suit me at all. He told me that the worst thing a young man could get was a job he liked that didn’t have a future and he was going to make sure that I would not get it. He wanted me to stay in school and I did. Thanks Dad.

I worked hopper cars during Christmas break and it was less fun, BTW. I remember working in the evenings and looking at the temperature on the Allen Bradley clock tower. It always seemed to be 5 below zero. I would work as fast as I could out there by the tracks, get the cement moving and then rush into my father’s office and sit in front of the heater. My co-worker, LC Duckworth, used to sleep in front of his own propane heater very close. I couldn’t stand it because it let out these terrible fumes. He had no complaints until he started his pants on fire. We put him out w/o any lasting damage, but he never sat near that heater again.. LC was the strongest man I knew, but his ability to sleep almost any time was his unique skill. I learned it from him.

My father retired when he was only fifty-six. He already had thirty-six years in, since he got credit for his time in army. I can understand why he wanted to quit. The job was noisy, dusty and hard. But the plus side is that he had lots of friends. His job involved loading trucks and he knew all the drivers. It was fun to watch. It was a different man I met when I went with my father to work, a happy man with lots of social connections. Retirement was a bit of a mistake, IMO. But I suppose he thought it was worth it. At first, I think it was. He had time to read and relax. It deteriorated after that.

We drifted apart as parents and children often do, when we moved away. In the FS, you are FAR away. My father had a blind spot when it came to this career, BTW. It was the only time I had to really disagree with him. When I told him that I planned to take the FS test, he told me not to waste my time. He said that such careers were “only for rich kids” and that I could never get a job like that. Had I taken his advice, it would have been true. I can’t blame him. It was just farther than he could see. I think that is a big problem for the “disadvantaged”. They hold themselves back with low expectations.

I didn’t make it back in time when he died. My sister called me and I got on the next flight form Krakow. But the next flight was the next day and then I got stranded in Cincinnati. When I called to tell my sister I would be late, my cousin Luke answered and told me that my sister was at the hospital and my father had died. I figure he died as I flew over Canada. I remember looking down at the savage beauty, the forest and the frozen lakes and thinking it was over. I don’t know if I REALLY thought that or if I have just created this memory ex-post-facto. The mind works like that.

My father never made much money, but after my mother died he spent even less. He never went anywhere, didn’t waste money on clothes and ate mostly bean soup, cabbage soup and kielbasa. He used to talk about his stash of “cold cash.” We didn’t think much of it. But when my sister was cleaning out the freezer, she found around $20,000.00 in $100 dollar bills, wrapped in foil like hamburger. The old man hated banks and didn’t want to have any money that would earn interest that he would have to pay taxes. When dealing with old depression era people, it was a good idea to look around and don’t hire stranger to clean up those nooks and crannies.

According to what my sister told me, my father fell down and couldn’t get up. When asked how he was, his last words were, “I can’t complain.” He used that phrase a lot and it was not surprising he would fall back on it, but it seems an appropriate thing to say at the end. Happy birthday, Daddy. I still miss you. I hope my kids will be as lucky as I was. I can’t complain.