It is not surprising that an aspiring geezer like me would think that the “youth market” is overemphasized in public affairs, but let me give you some of my reasons. (BTW – notice the suspension of good taste characteristic of the 1970s in the youthful picture on the left You can’t see the platform shoes, very unpractical on the icy streets of Milwaukee.)

There is no Successor Generation, Just a Succession of Generations

We talk of a successor generation, but what we really have is a succession of generations, i.e. one after another. Rearranging the words slightly as I just did almost completely changes the paradigm and drains a little of the urgency. I really have to do the tedious digression in order to explain why we still view the world through this kind of generational prism.

The idea of the successor generation and the concept of generations on steroids in general is suited to a particular historical period that is now ending. The “greatest generation,” the one that survived the Great Depression and fought World War II, is implicitly taken as the starting point. The worldwide apocalyptic effects of this conflict and the economic depression preceding it, coupled with the never before reach of mass communication meant that people who experienced the war and its aftermath had a unique common experience that shaped them as a generation in a way not seen before or since.

The end of the wars, both WWI and WWII that so comprehensively changed the world was a kind of a starting point for a new world. This created the idea of a generational personality and this impression was strengthened when people with the war experience ruled the world and set the pace for an unusually long time. Their numerous children were the baby boom, the largest and most affluent up until that time. The Boomer conflict with GI-Generation parents played out as a clash of titan generations rather than normal piecemeal generational change. This was also something very unusual, but since we grew up with it and in its shadow, we think of it as normal.

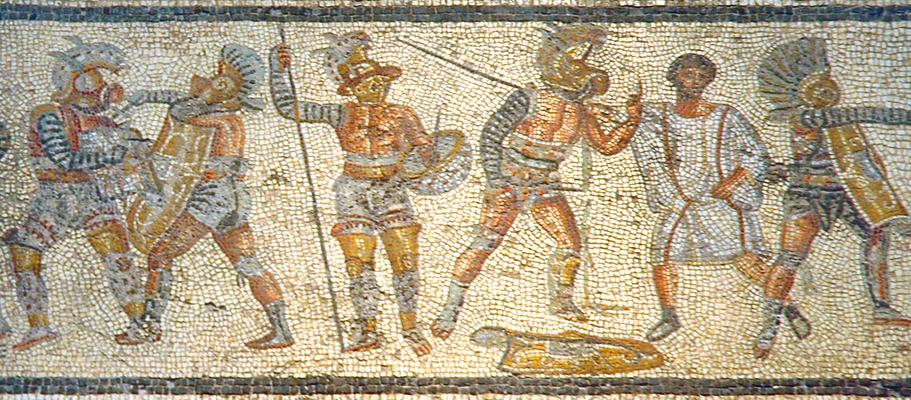

When I joined the FS, we were in the stages of transition to the “successor generation.” Supposedly, the new generations of leaders would be harder to deal with because they lacked strong direct memories of U.S. contributions during the war and American largess in helping rebuild Europe with the Marshall Plan. Worse, the heroic World War II generation was going to be replaced by the generation of ’68, with its formative memories coming from the riots, disorder and unrest of those days. Some of the former radicals still talked the talk, but twenty years of experience had made them a lot more reasonable. Our fears that the radicals would bring down the system were unjustified (unless you meant the socialist systems of the Soviet Empire.)

The Stone Throwers of ’68 Became the Capitalists of ‘88

If the youth that rioted to overthrow capitalism in 1968 – in Europe it was even worse than it was in the U.S. – could turn into the tranquil bankers and bureaucrats of 1988, maybe capturing the youth in their formative ages is not so crucial. But think of the even greater challenge that history just glosses over. The bureaucrats and bankers, the staunch U.S. allies facing down those rioters in 1968 had grown up during the severe indoctrination of Nazi Germany. It seems that people grow as they mature and they change with changing circumstances. Of course, maybe it is self-selecting bias, as the most extreme trouble makers just dropped out.

There is an old saying, variously quoted, that if you are not a radical when you are twenty, you have no heart, but if you are still a radical when you are forty, you have no brain. As I said, it is an old saying, at least a century old. Some changes don’t change or put more elegantly – plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Anyway, the big, lumpy generational changes that seemed have been the rule during our lifetimes were an anomaly. It will not be that way going into the future. Instead we will have more constant change spread across the generational spectrum. The need to make your impression on “the youth” in the first-formative stages of their lives will be less crucial, even if you still think it is crucial at all after looking at the history of the transitions between the self-consciously patriotic generation of ’45 and the self-described ’68 radicals.

For Everything there is a Season

Experience indicates that the best time to reach people is NOT when they are 18-20, much less an even younger age. They just get bored. You are a lot better off if you wait until they are 28-30. Few 18 year olds really care about politics, with good reasons. They don’t have a real feel for what they want and they have only a vague idea of what directions their lives will take. It is like asking them to choose door #1, #2 or #3, w/o knowing what is behind. They make better choices when they get better perspective, after experience begins to replace passion.

(BTW – I am not addressing basic tendencies and values, which seem to be established very early and may even be influenced by genetics. Here we are talking about things that we might express in public affairs messages.)

People are very much subject to natural unfolding development. There is a right time for everything. You cannot teach a kid to talk or walk before he is ready and the same goes for a lot of things. It is possible to be too late, but it is more likely that you will be too early. There are times in their lives when they are ready to hear a message or to make a change and a time when they are not.

Most 18 year olds are not ready for serious public affairs messages. I wasn’t. My kids weren’t. Reaching out to kids too early is like planting your flower seeds in February. Most will not germinate and those you plant in April will easily overtake and surpass any that do poke up through the frost. It is a waste to be too early. Beyond that, you face the constraint of selection. Only a minority of a generational cohort will be interested and/or able to act on any public affairs message. Among 18-year-olds you have an undifferentiated mass. To extend my garden metaphor, you are not only planting too early, you are also doing it indiscriminately, sowing seeds on rocks, sidewalks, sand and soil. Seven or ten years later you can make much better choices since you can better see which among them are or will be opinion leaders.

Ephemeral v Enduring

Anyway, patience is a virtue and waiting until the time is right is wisdom. Youth is overrated. People are much more influenced by the realities of their own life cycles than by the skinny dipping they made into an ideological pool as callow youth. If you are selling things that don’t last long, such as trendy clothes, cool games, fast food or various specific forms of entertainment, get those kids. If you are “selling” ideas meant to last – and be acted on – for a lifetime, wait until the time is right.