I heard this morning that one of our friends and allies in Iraq was murdered execution style by Al-Qaeda gunmen in Haditha. I recall visiting his home, watching his little kids play in the garden. I also remember that the people of Haditha could live and work in relative safety because of him.

Muhammed Hussein Shafir was a tough man and a warrior. His attackers knew that so they rolled in on him at his home with overwhelming force. Everybody knew who he was and everybody where he lived. There could be no isolation in a town the size of Haditha. This was the first violence in about a year in Haditha, but it was big. Twenty-seven police officers were killed in coordinated attacks around town. I am sure that I met some of them, but I don’t have details.

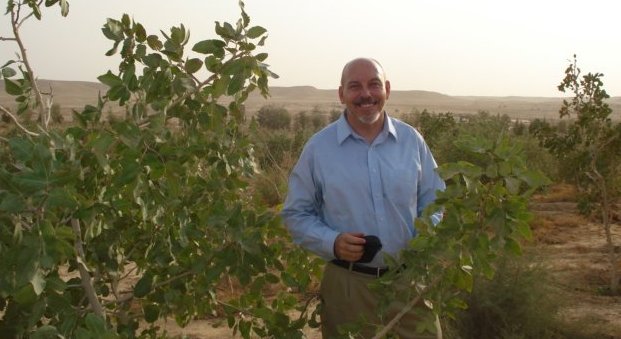

I did not suffer in Iraq. You get used to the dust and heat and there is beauty in Anbar. I especially like the turquoise colored Euphrates. Most important, Anbar province became relatively peaceful soon after I got there. I was lucky. But I knew people who were killed and more importantly I knew the danger threatening, not so much me – I had absolute confidence in the Marines – but our Iraqi allies. Something else I knew was that I was involved but our Iraqi friends were committed. My family was not at risk. Theirs were. After my year in Iraq, I knew I would go back to my country. They would stay in theirs. Twinges of fear and uncertainty that I felt sometimes wondering what was around a corner or hidden in a pile of trash up ahead, they felt always and everywhere. It would never be over for them.

Their courage was fantastic, sometimes the courage just to open a shop or carry on ordinary activities. Al Qaeda could be unbelievably cruel and their violence could be up close and personal. I recall an incident when Al-Qaeda beheaded a man and his eleven-year-old son for the “crime” of selling rice. With his courage in standing up to Al-Qaeda, Muhammed Hussein Shafir helped make ordinary acts by ordinary people require less courage. He knew he was making himself a target for their hatred and vengeance and accepted the burden.

I was glad to get out of Iraq. I told myself that my job was done and I had nothing more to contribute. Others could carry on. I think I was correct in this, but I still felt guilty. Was I leaving too soon? Before the job was done? Anbar was becoming peaceful and prosperous in 2008 thanks to Coalition forces. The Marines had done good work. Of course, this kind of work is never done.

I no longer have ties with Iraq. It was one year of my life, an anomaly in my career, which otherwise concentrated on Europe and the Americas, places where I knew the languages and understood more of the culture and history. I didn’t want to continue in the Middle East & didn’t want to be involved very much in any sorts of security activities, in general. I still don’t. I am unsuited to them. You should do things you do well and security operations is not my strength. It was important work; I worried that the job I did in Iraq was inadequate but it was the best I could do. I don’t think I could have done better. Maybe others could.

I knew two Hadithas. The first is the one I saw the day I arrived in Anbar. It was dirty and dangerous, still burning from the recent war. Then there was the one I saw in my last visit, full of life, activity and color. I told myself and I believed that this was “true” Haditha. I hoped that I had helped bring that about at least in a small way. What now?

I didn’t know Muhammed well, but I knew him well enough and I knew Iraq well enough to mourn the passing of a courageous man and fear for the passing of a fragile peace for people I learned to respect. I really don’t know what more to write.