Just getting there

Getting to the Moyers Tree Farm means driving for miles along twisty mountain roads, probably the most convoluted major roads in the Commonwealth of Virginia. They named it Highland County for good reason. If fact, Highland County has the highest average elevation of any county east of the Mississippi. This gives it a New England feel. If you were just set down here w/o orientation, you might think you were in New Hampshire, not Virginia, but Moyers were Virginia Tree Farmers of the year and they hosted their first Virginia Tree Farm landowner dinner at their place. It was worth the drive along those convoluted roads.

Virginia Tree Farmers of the year

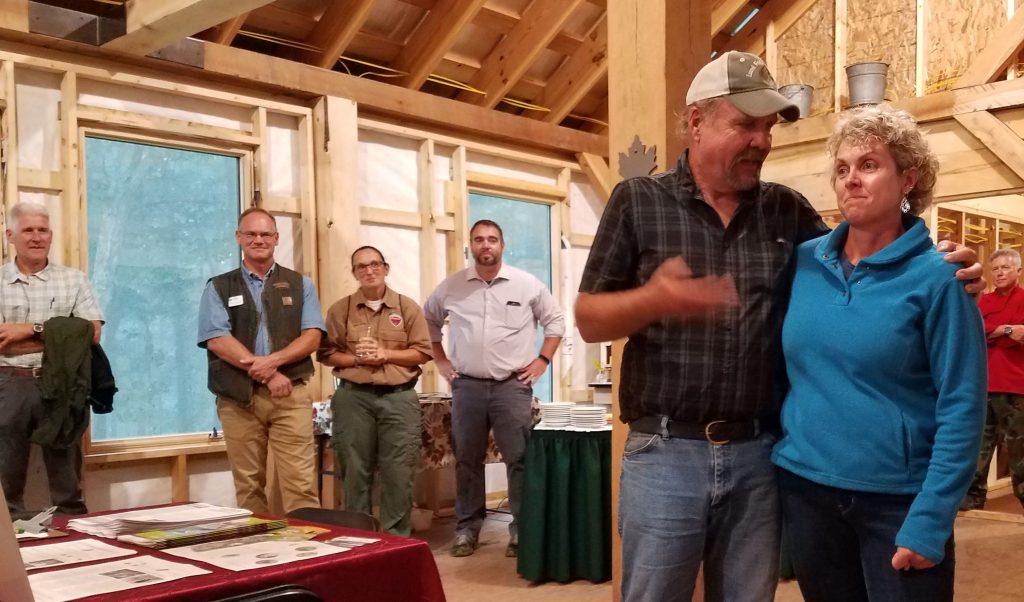

The Moyers are superb stewards of their land, as I have written elsewhere. All our tree farm members are good stewards. That is the ticket in. Moyers are a step beyond because of their exceptional commitment and outreach to the community. Ronnie Moyers and his daughter Missy displayed this during the program for about 30 landowners.

Caring for your land is part science, part art & part experience, but all these parts are united by passion. We learn from books. We learn from courses (lots of good and almost free ones offered by Virginia Tech, DoF etc.) and we learn from experience. Most of all, however, we learn from the interaction of all these things with the land we love – think, do, reflect and do something better. There is no shortcut this understanding, but there are ways to get a head start. We can learn from the informed experience of others, and a good way to do this is to at landowner dinners. This one was especially useful.

Maple sugar

We started out at the Moyers’ sugar bush. They have 35 acres of maple trees tapped for maple sugar. Ronnie rigged up a system of tubes that brings the sugar water to the sugar shack, where they boil it down to syrup. The Moyers use traditional methods, i.e. heat, and a traditional fuel source, i.e. wood. Wood is in local surplus these days because of the high ash mortality. Ash makes very good firewood and it is available to anybody willing to get it. Missy emphasized how much wood it takes to do the job. You have to boil 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup. They have a lot of it stockpiled, as you can see in the picture.

Ways to make syrup

I was unaware that there were other ways to make maple syrup out of maple sap. The new was is by reverse osmosis. Who knew? Missy explained that it is important to them to make it in traditional ways for cultural and aesthetic reasons. How you make something can be as important as what you make. The traditions are important to the community. Virginia is not a big producer of maple syrup. We have plenty of red maples, not as many sugar maples and outside Highland County almost none of them are tapped for sugar. ¬¬little Highland County produces more than half of all Virginia’s maple syrup, but even here it is not major production for supermarkets. Rather, it is more related to what we might call agro-tourism. Missy said that during the maple syrup festival last year, around 4000 visitors came to the Moyers’ sugar shack.

Oak regeneration & Microbiomes

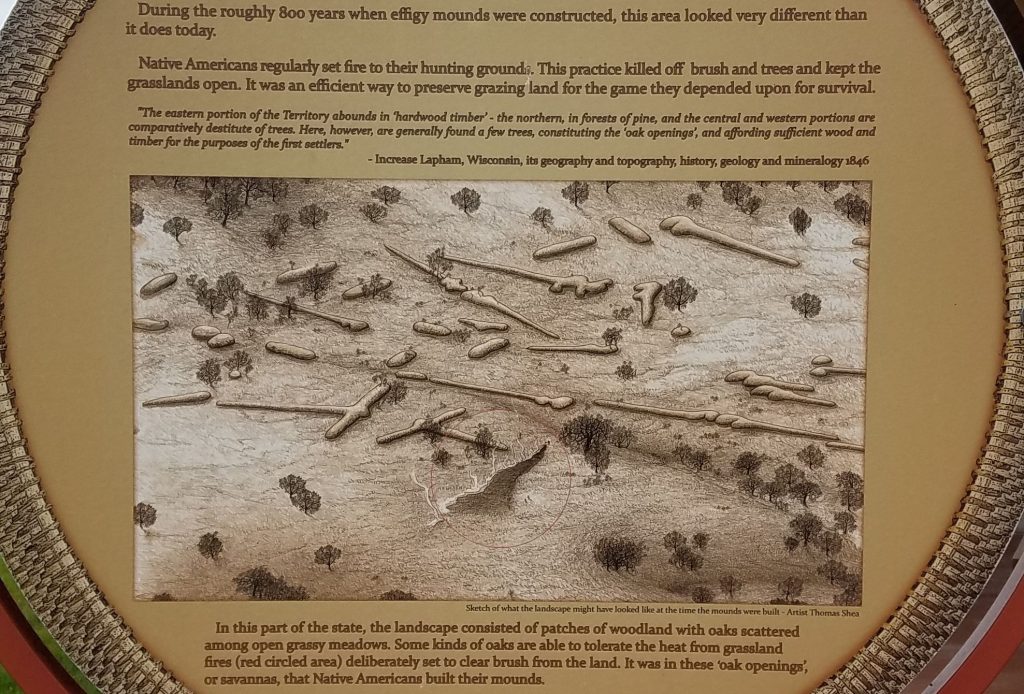

The Moyers farm features several different micro-ecologies short distances up or down the hills. The maples near the top of the hill quickly gives way to oaks a little down. As in many places in Virginia, there is concern about oak regeneration. We are worried about our oaks, and they suffer from oak decline. This is a non-specific ailment. It might be caused by stress of drought, soil compression, or maybe just old age. Trees live a long time, but they do not live forever and as they get older, their resistance to disease and bugs declines.

There was a lot of disturbance and regrowth in Virginia forests 80-150 years ago and a lot of our oaks were born in those times. An oak might live hundreds of years, but just like humans, not all of them make it close to their maximum life spans. You have to know something about the history of the land to understand the current biotic communities.

The oaks moved in as farms were abandoned, but one of the biggest changes came when the chestnut blight wiped out the American chestnut. Chestnuts were a dominant – predominant – species in Virginia west of the Blue Ridge, making up as much as 25% of the total canopy cover. The bight was first detected in North America in 1904. It reached Virginia about ten years later and a little more than ten years after that had killed most of Virginia’s chestnuts. It was a disaster ecologically and economically.

The end of the chestnuts and the start of a novel ecology

It also created an essentially new ecosystem in the span of about two decades. Oaks, hickories and poplars filled in the gaps left by the chestnuts. This is the Virginia forest our generation knew. Maybe this is not equilibrium that will be established. Maybe the oaks are part of transition that, at least in wetter forests will be dominated by red maples, beech and poplar. These kinds of thing play out over decades or even centuries, and it will all be complicated by climate change.

Speaking of chestnuts, they did not die out completely. The blight comes in through cracks in the bark and then kills the tree only to the ground. The roots survive and produce new sprouts, that can grow until they get old enough to get cracks in their bark and they die back. Ronnie found a sprout about 30 feet high. Who knows how long it will persist? The roots are at least a century old.

A new hope for the American chestnut

The blight is always present. It survives in beech and oak trees. It infects but does not kill them or cause them any significant harm in general. Beech, oak and chestnut are related species. Scientists have isolated the gene that allows for survival and researchers at State University of New York, Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF) have developed a trans genetic chestnut that has all the characteristics of the American chestnut with the one difference in the gene that protects it from the blight. This gene will not encourage successful mutation of the blight, since it does not kill the blight, but allows the tree to survive. In some ways, it is arguably a “win” for the blight, since it can continue to survive in chestnut trees w/o killing them – the dream job for a blight.

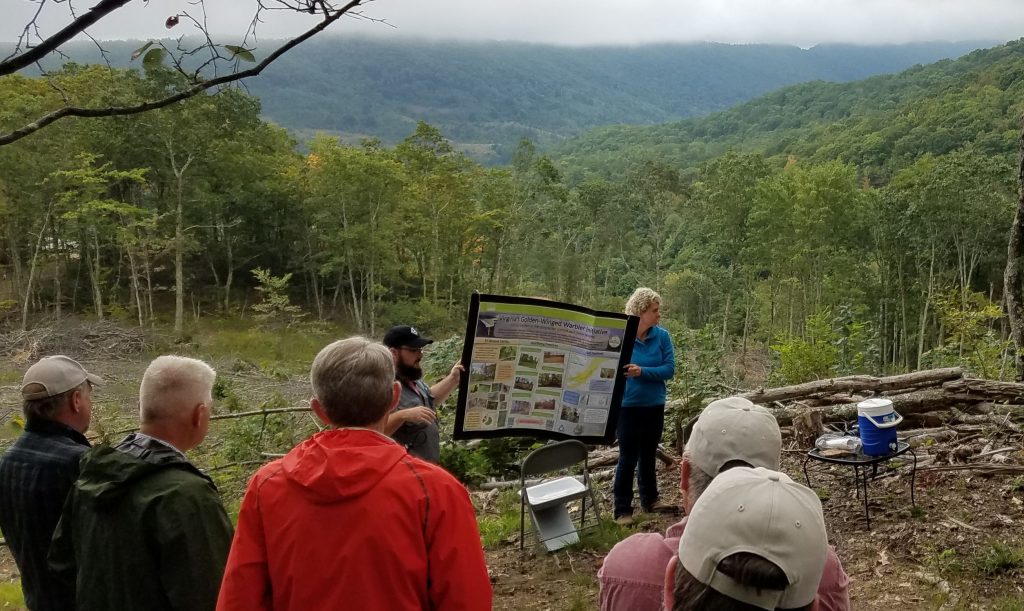

Golden wing warbler

Our last stop before the tree farm dinner was to look at what the Moyers have done to reestablish habitat for the golden winged warbler. This once-common but now threatened species requires a mixture of openings and old-growth forest. Moyers got a grant from NRCS to harvest a stand of generally less productive chestnut oak and to allow for root sprouts and forbs. Ronnie said the he had hunted in that woods as a boy, decades ago. The trees were mature then and were not much bigger when they were harvested. NRCS grants allow for the harvesting of this sort of timber, which would be marginally profitable or not profitable at all.

The unfortunate part of this initiative is that it may not work because Virginia is only part of the puzzle. The Virginia birds migrate to Columbia & Venezuela in the winter. The population of golden wing warblers in the Great Lakes is a little better off. They winter in the Yucatan. These two populations used to be mixed in North America, but now they are largely separated. How this will affect their genetics and survival is not known. On the plus side, these openings are generally good for wildlife and for regeneration of desirable species like white and red oak. While we hope, and scientists believe, that the initiative will help the golden winged warbler, it has all sorts of collateral benefits.

Good food

After the field day portion of the program, my colleague Glenn Worrell gave a presentation about tree farm and we had a wonderful dinner. Pulled pork is the standard fare at most tree farm and outreach dinners, and I am very fond of pulled pork. At this dinner, however, we had a catered dinner featuring a nice beef with mushrooms, green beans and potatoes, with a cherry cheesecake desert.

People don’t appreciate free

interesting permutation is that these dinners used to be free. We decided to charge $10 as an incentive to get people to come. $10 is not much, but when it was free, we got lots of no-shows. Now most people come. Human nature is funny. Sometime you can get more customers by charging more. People really don’t appreciate free.

I had to get on the road before it got too dark. I failed. It was like playing a video game with the twists and turns illuminated only by the reflectors on the road. Unlike in the video game, however, I would not just come back if I drove off the edge.

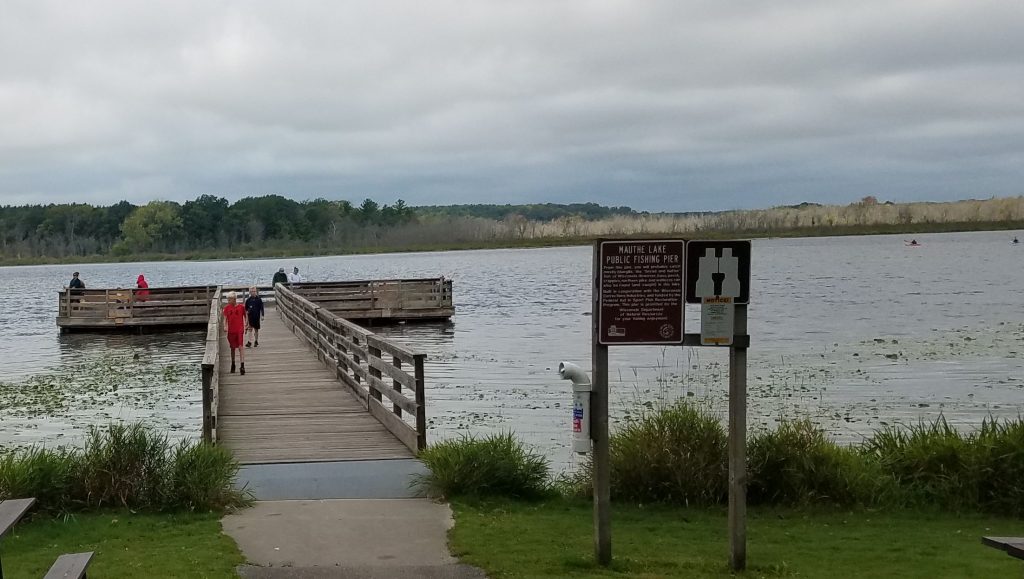

My first picture is the sugar bush, followed by the sugar shed with its wood supply. Picture #3 shows Ronnie and daughter Missy at the event. Ronnie’s love of forestry is inspiring. Missy did most of the organizing. Picture #4 shows the lecture on the golden warbler with the golden warbler habitat in the background. Last is a market tree, as least that is what we think it is. We estimate that tree is more than 200 years old. Native Americans used to mark trails and significant places, but bending trees to the ground. Sometimes they would continue to grow even in the supine position.