From death comes new life. I know that is true and amply demonstrated on the ecology of the land, but I am still upset by the near total death of the ash trees (Fraxinus).

Ash trees

The ash were among my favorite trees, with their glad grace, dark green leaves and fast growth. Ash quickly formed groves. They were among the first to leaf out in spring and in fall turned a beautiful golden, not yellow but really more golden color. Except the white ash. They could turn a beautiful maroon. Beyond those things, I liked ash because they seemed almost impervious to disease. You could plant ash, or more commonly just let ash plant themselves, with reasonable certainty that they would cover the area w/o problems. This last part proved not to be true.

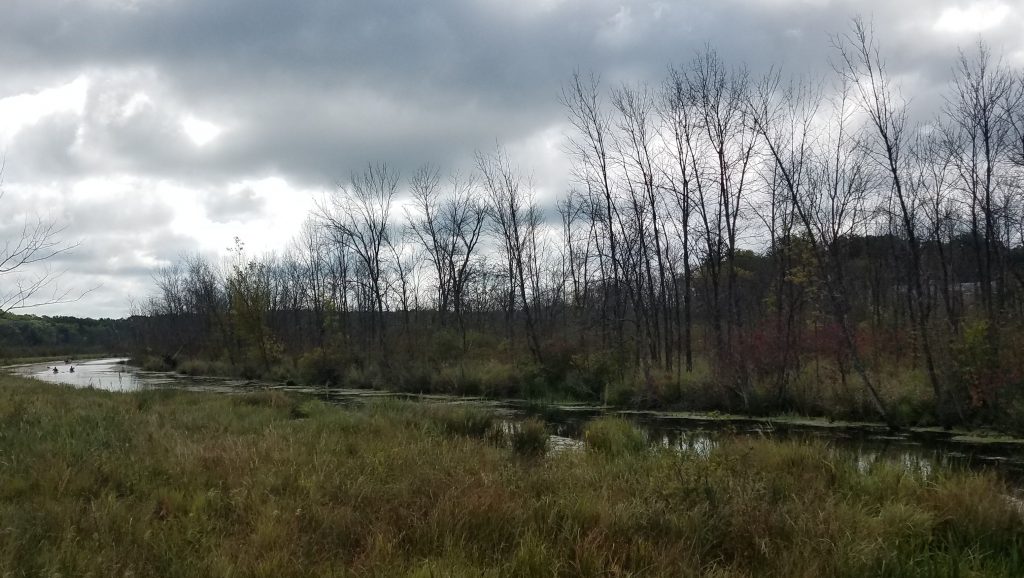

Ash were very common in southeastern Wisconsin. That and their tendency to form groves of almost purely ash has made their rapid demise because of the emerald ash borer more painful. You can see the destruction easily just driving down the roads. That was exacerbated by another of the ash characteristics. They were a pioneer species, quickly filling in disturbed areas, like areas near roads.

Kettle Moraine again

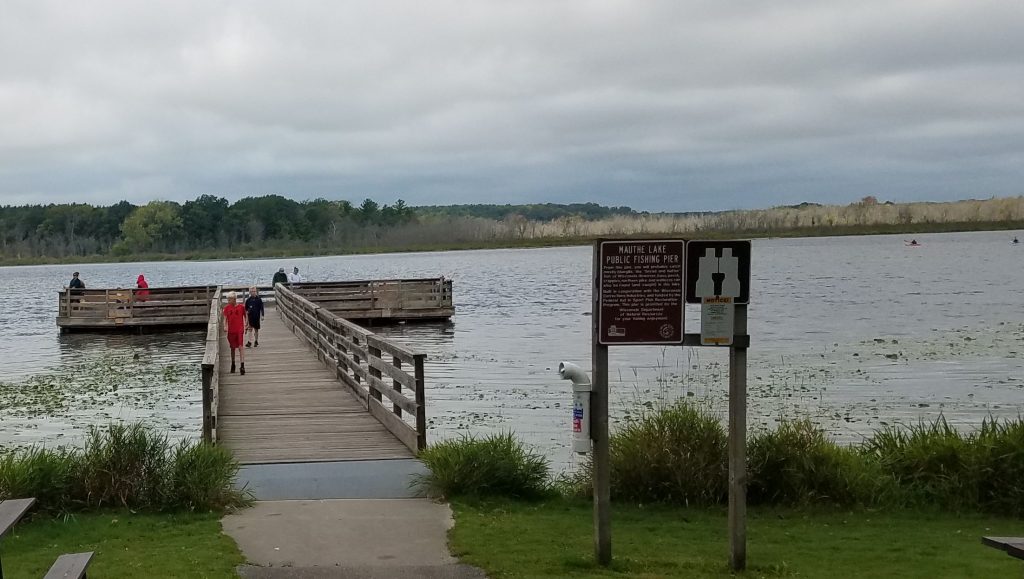

I drove up to Kettle Moraine State Forest (Northern Unit) along Highways 41 and 43 and the Götterdämmerung of the ash as particularly noticeable. By the time I arrived at Mauthe Lake I was in a profoundly sad mood and I was uncharacteristically pessimistic. The weather conspired in this. It was overcasts and gray. I thought for sure it would rain, but I needed to do my walk around the lake, as I have been doing for than fifty years.

Mauthe Lake is a gift of the glaciers. It is pretty, but not remarkable. The lake is much more prominent in my personal landscape of memory than on the ground. It was carved out during the most recent ice age and is the headwater of the Milwaukee River. The Milwaukee River does not start here, but flows through early on. Mauthe Lake is important to me because it was where I first learned about conservation, where I came to appreciate the Ice Age and where I saw how landforms interact with biotic communities. I took part in a nature camp there when I was in 5th Grade. It made a lasting impression. In HS, I rode to Mauthe Lake on my bike. In college, I hitchhiked down. I have driven up here dozens of times. The visits bring back memories and I can see the changes that have been taking place over the decades. I expected the dead ash. I had approached the visit with trepidation last year. They were mostly dead by then.

The old trail

The walk around the lake is two miles. As usual, parts of the trail were flooded. This is not a problem. Once your feet get wet, they cannot get any wetter, so you just trudge on. You start off in a cedar swamp, with white cedar, tamarack and – until recently – lots of ash. It was on this leg that I felt the deepest discontent and rehearsed the narrative of loss. As I walked, however, I got more cheerful. Maybe it is the stages of grief. I was moving on to acceptance. More likely it was a prosaic combination of seeing more of nature and an improvement in the weather. The sun started to come out and that makes your disposition sunnier.

The turning point came as I crossed the Milwaukee River and started into the mixed and pine forest on the other side. There are a lot of big oak trees there, mostly bur oak. We had the big old oaks surrounded by lot of small and newly deceased ash trees. This reminded me of the impermanence of … it all. At some time in the not very distant past, this ground was probably sedge savanna, with a few big oak trees, some still extant. The oak savanna was almost certainly the result of fires set by Native Americans. I speculate that settlers grazed cattle there. After that, when the land because State Forest, the ash moved in. In other words, the ash were part of the cycle, not the beginning nor the end. This does not take the sting out of their loss, but it does put it into perspective.

You come into a red pine forest as you gain a few feet of elevation. These pines were planted in 1941 and thinned four times. This forest now looks a lot like an open southern pine forests, with a lot of sunlight hitting the ground allowing for diversity. My loblolly on Brodnax look very similar. The red pines are a little bigger than mine, but surprisingly not that much. The Wisconsin trees are nearly 80 years old; mine are just over 30. Trees grow faster in Virginia. Of course, all trees grow faster in their exuberant youth and then plateau. My loblolly will not end up bigger.

I remember the changes in this forest, as least I think I do. I remember my childhood hike in these woods and how I was impressed with hot deep and dark it was. The pine needles formed a thick carpet and there was not much growing under the trees. This was how they did forestry in those days. These days, they like to let in more light. It sacrifices some timber value, but creates a lot more wildlife habitat and species diversity.

What next?

All of this made me ask the “what’s next?” questions. The ash trees are gone. We shall not soon see their like again. What is going to come up instead. Something will benefit from this. I observed tamarack, black willow, alder, maples, birch and – surprising to me on the damp land, bur oak. In some places the cattails had become more profuse. Maybe the treed swamp will in some places become a marsh or a sedge meadow. The trees suck up water. Absent the ash, maybe more water will stand.

I observed last time and still now that in some isolated places the ash were still standing and healthy. Sometimes dead ash were standing next to lives ones. What happened? I understand that ash trees in Asia resist the ash borers. Ash borers in Asia are endemic, but not as decisive. Some American ash likely also do not taste as good to the borers or maybe have some characteristic making the less attractive. In this maybe we have the seeds of recovery. I have a picture of the live ash near the dead one with the backdrop of a beautiful sedge meadow. The future?

We think the environment we first saw is THE proper environment, that the forests and fields of our youth was the way it was supposed to be. Nature, in fact, is dynamic and impermanent. Our nature was just one short and changing scene in the endless drama. As I described with the big oaks, it was not what had been or what had to be.

Along the trail, I passed some kids with their parents and a group of what looked like high school kids. They were looking at each other, the boys paying attention to the girls and the reverse. They were not paying particular attention to the forests around them, but they were drinking it in unawares. This is their baseline. Maybe the next generation will think that the cattail marsh next to the river is the way it is “supposed to be.” If sometime the ash recover and recolonize the fenland, these old people of the future will decry that mess and invasion, the trees sucking up water and shading out the cattails.

I know I should more joyfully embrace impermance. I know that intellectually. I know that future generations will not feel that way and maybe even I will not long into the future.

From death comes new life. The environment endures and adapts. But I still miss my ash trees.