The Brazilian State of Parana spreads across region where four biological regimes meet and mix: the Atlantic forest from the east; from the north tropical species; the south provides a sub-tropical temperate mix, while the west is represented in more arid, seasonal rain vegetation called sertao.

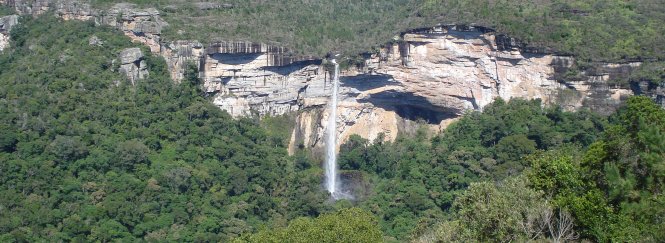

All four are represented in the Vale do Corisco in the pictures above. The valley is a unique ecological zone because of the mixing of species and it is very beautiful. The water falls about a hundred meters straight down. You can hear the loud splashing miles away, about as close as you can get since no roads or even good paths lead to the base of the falls, and none are planned. Even getting to this distant overlook requires a drive over dirt roads and a key to a gate on private property. The falls creates its own, much moister, sub-climate. When we passed in the morning, the whole valley was completely obscured by a heavy fog. Valor Florestal owns this valley and they are conserving/restoring it to its natural state.

As impressive as the falls was, the trees on the surrounding plantation were equally remarkable. Valor Florestal manages more than 100,000 hectares (significantly more than 200,000 acres) of forest. A little more than 60% is in productive commercial forests. The rest, around 40%, is in ecological reserves. Foresters in Brazil are like their cousins in America. They want to produce wood, but also protect and conserve natural areas to provide wildlife habitat, maintain native species and protect water resources.

Loblolly pine grows well in Brazil, but various species of tropical pines grow even better. These tropical pines are replacing loblolly and slash pines everywhere where frost is not a factor. In this respect, microclimates are very important. Sometimes a few meters of elevation or proximity to a body of water of an open field can make the life or death difference. But where the tropical pines grow, they grow big.

I could not believe it when Renato told me that a stand of pines that I would have guessed were at least seventeen years old, were only six. A picture is worth 1000 words so look for yourself. A sixteen year old or even a fourteen year old stand is ready to harvest for saw timber. The fastest growing trees seem to by a central American pine (pinus maximinoii) but three varieties of Caribbean pine (caribaea bahamensis, caribaea, & hondurensis) were also almost growing fast enough for us to watch them. Some of them are ninety feet high by the time they are seventeen years old. Valor Florestal is in the lead in developing these species and the tests are looking good in the first generations. It looks probable that loblolly and slash will be replanted only in places where frost hits. Below you see a sixteen year old stand of p maximinoii with Renato to show the scale.

It was with some sadness as I watched the last stand of a thirty-two year old loblolly forest. Renato told me that we would not see this again in Brazil. They will be going with a shorter (22 year) rotation for loblolly. The tropical pines may be significantly faster. Below is a thirteen year old p caribaea and Tim for size comparison.

Such high productivity is very good for the environment. It allows the production of wood that societies around the world need to be sustainably grown on smaller acreages in less time. This is what allows the conservation of the more sensitive natural areas I described above. The truck below is driving past a SIX year old stand of Caribean pine.

Nevertheless, while I am impressed by the speed, it takes some of the satisfaction out of forestry. I like to think of a forest as the living organism that links our past with our future. I like the idea that I am benefiting from the work of previous generations while I am planting for my grandchildren. If the rotation becomes fast enough, it will just be another short term crop. I guess I like the forest part of forestry more than the business part. Maybe I should start growing oak trees. Take a look at the falls one more time.