The great thing about ancient history is that we learn more every year. History is not just out there to be discovered. It is the creation of historians, who fit a narrative to events that are otherwise just one darn thing after another. The narrative is necessary. It may not be wrong, but always incomplete. We seek to come closer to truth, knowing that we never get there.

Recent advances in the science of genomics and climate science have made possible an understanding of ancient history not possible even a decade ago. Human events play out on a changing stage. The climate and the disease load has changed a lot during our history and it has made a difference. History is contingent. There is no such thing as fate or destiny. Shit happens. But it happens in patterns that we can try to understand.

The Roman Empire flourished during a particularly favorable climatic time. It was warmer and wetter than the time before or after. The author calls the period in the first and second century as the Roman Climate Optimum (RCO). From the time of Augustus until the reign of Marcus Aurelius there were also no pandemics. These conditions changes about AD 180. Roman leaders made some good and bad choices, but their margin for error was smaller.

Events outside the Empire also were affected by rapid climate change. Warmer and wetter weather on the Eurasian steppes got cooler and drier, inducing movements of peoples. The Huns burst out of Central Asia pushing everybody else.

In the course of one lifetime, the “eternal empire” was disintegrating. The author contends that the Empire in the West fell from 404-410 and not 476, when the last emperor was deposed. It was more a decay than a decline & fall.

The Romans lost control of their borders after the defeat and death of Emperor Valens at Adrianople in 378. The Barbarians did not plan to destroy the Empire. They just wanted a piece of the action. Absent the challenges of climate change, disease and the attendant demographic challenges, the Empire might have survived.

An interesting contingency is the plague of Justinian. Justinian was in process of reestablishing Roman power, when his base was destroyed by the plague. Recent DNA analysis indicates that this was indeed the black death, bubonic plague.

The interesting contingency here is that it hit the Romans hard, but did not as much affect the steppe nomads of thinly populated areas like Arabia. Had the plague not hit when it did, Roman power would have been reestablished and Islam never would have spread as it did.

One more thing to recall. The Roman Empire evolved into a territorial state. All people of the Empire became Roman citizens in AD 212. People living in Egypt, North Africa, Asia Minor or Gaul were citizens. It was like California, Texas or Florida being integral parts of the USA, although they were not original members. Most of the Empire’s leadership came from outside Italy after the 1st Century. Some former parts of the Empire were never run as well after the fall of the Empire.

Anyway, good book. I have been reading these things since at least 1966, when I borrowed my father’s copy of Edward Gibbon’s “Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire.” It continues to be an interesting period.

BTW – I suggest that Michael W. Fox take a look at this book. He mentioned studying with William McNeill. This is the kind of book that takes the big sweep too and the author frequently refers to McNeill as a source and inspiration.

The Fate of Rome

https://www.amazon.com/Fate-Rome-Climate-Disease-Princeton/dp/0691166838/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1520024102&sr=8-1&keywords=the+fate+of+rome

I got Nova’s “Fire Wars” video as part of my study of fire science. It is a great complement to the many books and magazine article. To actually see the flames and the firefighters at work, and hearing them speak adds greatly to understanding. If a picture is worth a thousand words, the video and explanation is worth even more. Seeing an example of the fire-ball that comes from a fire blow-up is much more impressive than reading about it. The video also includes computer graphics that shows in detail how the winds and topography interact. I read the classic “Young Men and Fire” about the fire in Mann Gulch that killed thirteen smoke jumpers in 1949, but could not picture and really understand the event until I saw the actual topography and the graphics that showed the fire’s progress.

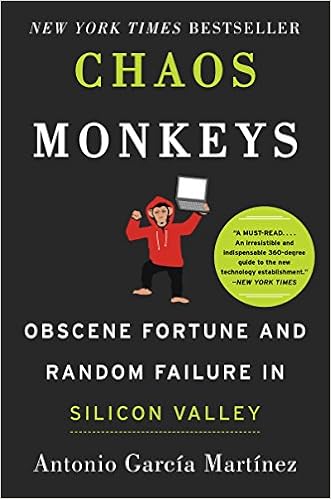

I got Nova’s “Fire Wars” video as part of my study of fire science. It is a great complement to the many books and magazine article. To actually see the flames and the firefighters at work, and hearing them speak adds greatly to understanding. If a picture is worth a thousand words, the video and explanation is worth even more. Seeing an example of the fire-ball that comes from a fire blow-up is much more impressive than reading about it. The video also includes computer graphics that shows in detail how the winds and topography interact. I read the classic “Young Men and Fire” about the fire in Mann Gulch that killed thirteen smoke jumpers in 1949, but could not picture and really understand the event until I saw the actual topography and the graphics that showed the fire’s progress. Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley

Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley

“Investing in Nature” was published in 2005, i.e. more than ten years ago. It is useful to remember that, since some of the ideas in it are now more mainstream than they were back then and we need to appreciate it in its time. Books like “

“Investing in Nature” was published in 2005, i.e. more than ten years ago. It is useful to remember that, since some of the ideas in it are now more mainstream than they were back then and we need to appreciate it in its time. Books like “