At work we are experimenting with using games in public affairs, so I have been thinking about them and reading about them. I just got a book called Changing the Game, re how video games change ways we do business. We are very much influenced by games because games create reality. I plan to write a couple posts on this general subject, but to get my thoughts rolling I considered Monopoly.

Left is the Polish version of Monopoly. I didn’t have the original American version, but I used the familiar names of properties in my post. The proliferation of Monopoly around the world shows its general appeal.

Monopoly was the game we played when I was a kid. I played it with my sister and with my friends. I didn’t realize what it was teaching me and the subtle persuasion that was going on. Learning and persuasion are closely related, of course. When we learn a system, we are simultaneously persuaded that it is good and/or useful. So what does Monopoly teach/persuade?

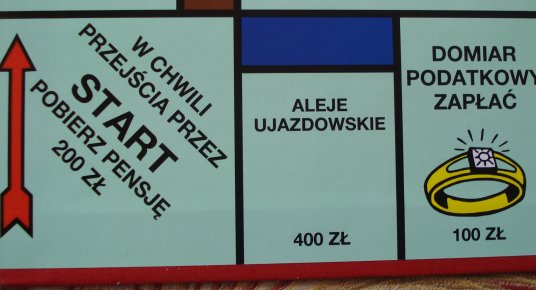

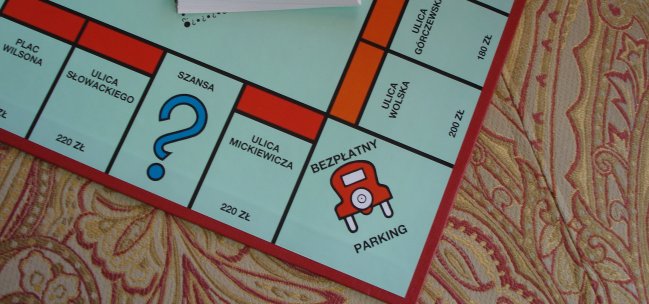

You learn a lot about statistics. Dice produce random results within a pattern. There are thirty-six possible combinations of two dice that produce the twelve numbers we might throw. Seven is the most common number, since you can get seven with six different combinations of the two dice. Least common are two and twelve, since there is only one combination that can produce each of these.

The Monopoly board accounts for this. You cannot buy a property that is seven steps from “GO” and the most common landing spaces are occupied by “Chance,” or “Community Chest.” The probabilities created by the dice would become less important as the game progressed, except various events of the game tend to bring you back to certain places. You often are told to “advance to GO”, which resets the probabilities. Seven spaces from “GO” is “Chance,“ BTW. You are also frequently told to “Advance to the nearest RR” or sent to jail. Seven spaces from Jail is “Community Chest” and there are no monopoly property possible seven paces from a RR except the green property North Carolina.

Given all the permutations, it is generally the lower cost-lower rent properties that get most of the business. Mediterranean and Baltic are the most visited properties, but it is hardly worth having them, even with a hotel. Boardwalk is the killer property, but people tend not to land there and it costs a lot to build houses and hotels. IMO the best combination of affordability, frequency and income are the Red group of Illinois, Kentucky and Indiana. The next best are the Orange New York group. I am sure that somebody has figured out exact probabilities.

The winning strategy is to get the best property you can and build as soon as possible. There is a big advantage to being first since you will get the resources to expand (and deprive your opponents of same).

Fortune favors the bold and a person who is timid and refused to deploy his current money to produce future income cannot win. Of course, the reverse is not necessarily true. You can know all the things you should know and play superbly and still lose. If you could just do something with a certain guarentee of success, it wouldn’t be a game anybody would play. There is no uncertainty in dice, but there is probability and risk. In Monopoly, you can assess risk. Over the long term you will win if you do the right thing. Over the short term, such as a particular game or even lifetime there is no such guarantee. That is the nature of risk.

These are really good life lessons. I learned probability from Monopoly before I knew about it in school. We practiced simple math. Got a good short course in negotiations and a chance to observe human nature in wealth and poverty.

The world view we got from Monopoly was that this is the way life was. We had early free enterprise, followed by consolidation and then Monopoly and bankruptcy for all but one big winner. Although that last part was never achieved in our games, which was another lesson. We always made deals (not permitted by the official rules) to help each other save face. We also noticed that the bankers tended to have more ready cash than their property holdings seemed to justify.

The games usually ended when it became clear enough who was winning and everybody got bored, or else somebody got mad enough to upset the board or end the game abruptly. We had several sets of brothers who played with us. Inevitably one or more would resort to petty violence in response setbacks in the market, thereby ending the game. I guess it was like real life.

Clearly, the game persuades us that some behaviors are useful and others not. I don’t think Parker Brothers had support for Capitalism in mind when they started to sell the game in the 1930s. In fact, I read that the precursor to Monopoly was invented by a socialist who wanted to show the pernicious nature of private ownership. It just goes to show the law of unintended consequences that it taught generation of American kids about the virtues, if risky ones, of the free market. The mistake that Monopoly teaches is that the free market is a zero sum game, with winners in proportion to losers. In fact, the free exchanges in a market economy increases general wealth, although not in equal measure. I don’t think we can blame Monopoly, but this zero sum mentality is the leading cause of misunderstanding of the market. Of course, games need winners and losers. They are only games after all. And one reason we like games is that, unlike life, they provide definitive results, but we would not like those kinds of results in real life.

Anyway, kids don’t play Monopoly like we did. They have other options.