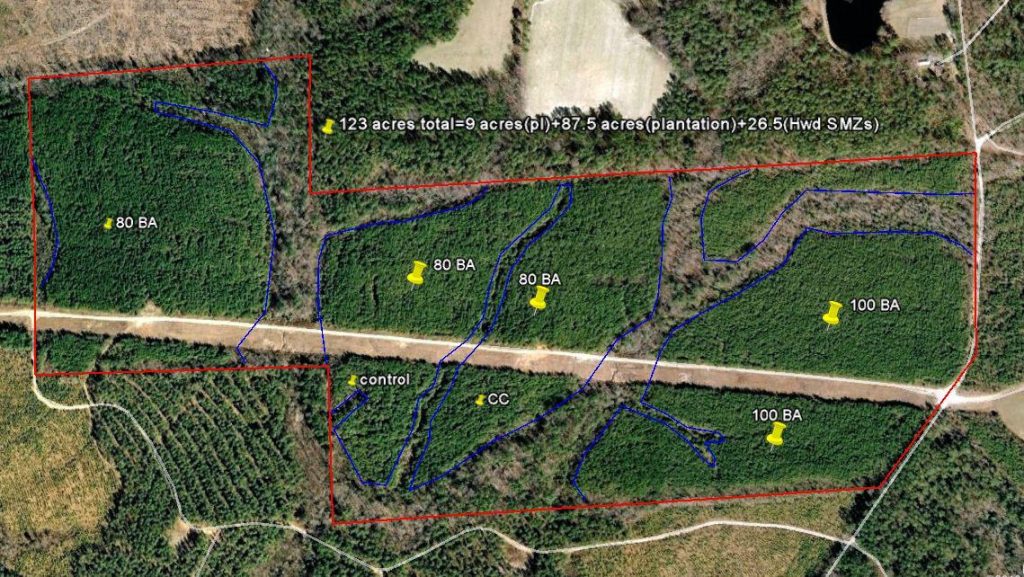

We have big plans for my little piece of forest. I say “we” because the planning has grown beyond my expertise. Yesterday, Alex & I met with Eric Goodman from Kapstone, Frank Meyer from Gasburg Forestry and Katie Martin, a wildlife biologist to talk about plans for the Freeman property. The local hunt club also has a stake in all this, so I have to bring them in too. As I described before, the woods have been thinned to different densities, to see which ones produce the best harvests. We will also use different management regimes to test for different outcomes. Some parts will be biosolids; others will be burned or treated chemically.

This will be a kind of demonstration forest for this part of the Virginia Piedmont. Already there is talk of bringing 4H, Boy Scouts and school groups. We will probably put in a path. Although Brunswick County is a center for forestry in Virginia, there are few places nearby to see forestry at work. The advantage of our land is that it will have several different types of cutting and management within a short distance. I think it is important for people not involved in the business to understand it, especially understand the renewable and sustainable aspects. Most people don’t understand this part. It shows in everyday expressions, like “Save a tree: don’t use so much paper.” There are plenty of reasons not to waste paper, mostly related to the energy it takes to make and move it, but using less paper in any reasonable sense does not make a difference in saving trees. You have to thin trees, whether or not you can sell the pulp to make paper. If you don’t thin, they die anyway from overcrowding or bug and if you don’t thin, even more of them die in these ways. It is like planting flowers or vegetables in a garden too close together. Land can be overgrazed and overused. It can also be “over-treed.” And the trees grow back. This is what I have learned over and over again as I look at harvested timber tracts. As I take pictures and document the growth of my forests, it is clear to see. I expect to have more total green growing in my forest next year, after the thinning, than we had this year before.

One of the more interesting parts of the plan is longleaf pine planting. We plan to mix longleaf with loblolly. Frank looked at the dirt and told us that we needed to plant to longleaf farther down the slope, where the soil had more sand and less clay and where the microclimate would be a little more moderate. That is the kind of knowlege you can get only from experience and that is why I need the help of all these people who know local conditions so well. If things go as planned, we can harvest the loblolly in fifteen years leaving a stand of longleaf. Longleaf pine used to be very common in the south, but have lost ground, since they require specific conditions; most important is burning to get them started. In other words, longleaf pine is a fire dependent species that didn’t do as well when fires became less common.

Katie will come up with recommendations for wildlife habitat under the power lines. We can plant warm season grasses and a mix of wildflowers, she says. It won’t cost me very much, since we probably can get some cost shares from Dominion Power (it is under their lines and our activities will save them the worry of cutting as well as provide a little “green PR”) These plantings will help restore something like the habitat common in this part of Virginia hundreds of years ago. It will also give us a chance to see how well these habitats respond under local conditions.

In some ways I am more excited about the grassy ecosystem than about the trees. I love trees and the longleaf will be treasures, if we can get them to grow well. (Once they get going, they are very robust, but the start is tricky, especially where we are, near the natural edge of the biome.) But as we talked about the future of this piece of ground, and plans for activities years from now, the big thinning to take place maybe in 2026, I realized that my chances of seeing big longleaf growing on my land are small and my chances of seeing a mature ecosystem is zero. I was glad to have Alex with me. He can bore young people with stories of the creation, when he is an old guy.

The grass and forbs will mature this year and a few years from now they will form a working ecology. I have reasonable confidence that I will be around to see that. The trees belong to the next generation. Understanding that fills me with an exquisite mixture of sadness and joy. I am glad that something will be around after I’m gone, but it reminds me that I will be gone.

The picture up top shows some longleaf seedlings near the Virginia-North Carolina border. They are just coming out of the “grass stage”, called that because it is really hard to tell the little pines from the grass around them. You would not be able to see them during the summer, since they would be covered by and the same color as the grass. The grassy vegetation has to be controlled. In the natural run of things, a fire would do that, allowing the pines time to grow above the grass. I was told that this was an old farm field, so the trees got a head start before the grasses came in. Some of the bigger ones in this stand have done that, as you can see in the picture.