Today I am in Rio following the Smithsonian folks and I got to go with them to the Fundação Roberto Marinho. This organization works throughout Brazil broadly speaking on educational projects and knowledge creation and dissemination. This includes museums, which have a strong educational component. Its mission is similar to Smithsonian’s in these respects. They were proud of their new Museum of the Portuguese language and Soccer Museum in São Paulo. Both this museums explore the social implications of their subjects and are both creators and disseminators of knowledge.

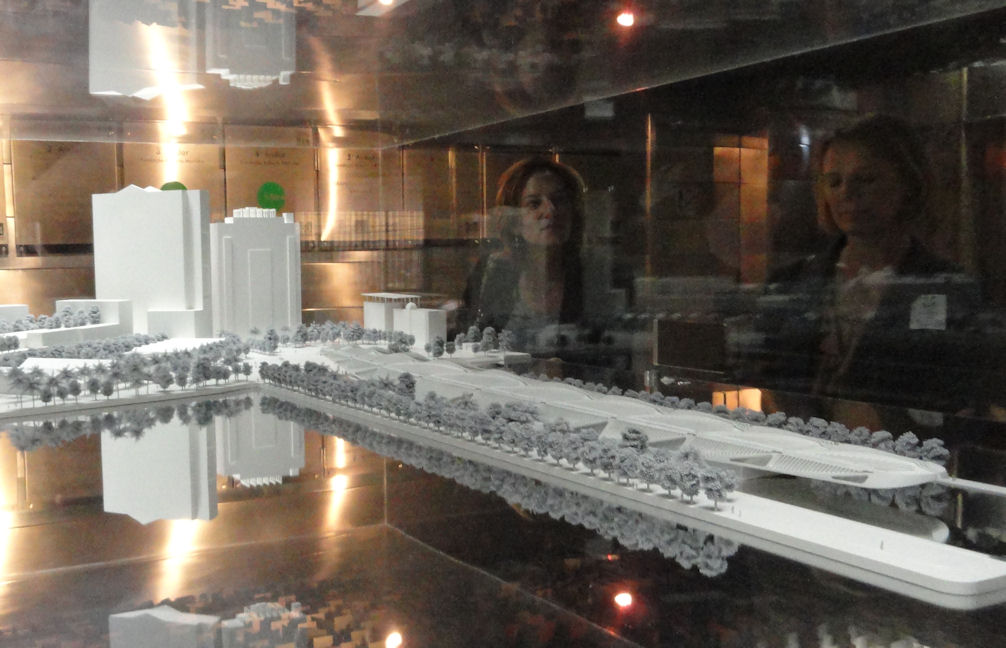

A ground-breaking museum to be opened soon is the Museum of Tomorrow (Museu do Amanhã). It will be in the area of the Rio port district, which I wrote about before. The museum is different in that most museums preserve the past; this one will be aimed at the future, as the name implies. It will be about the science of a sustainable future. Organizers know this hard to do. It is very easy for a museum of the future to become a museum of futures past. It might just become quaint. If you visit, “Tomorrow Land” in Disney World, for example, you can see what people of 1960 thought it would be like today. It is quaint and funny, but no longer “future”. Actually, Brasília is a bit like that, a 1960s version of the future. Foundation people hope to avoid this fate by commitment to constant renewal. Let’s hope. You can see the projections of the Museu do Amanhã in my photo nearby.

I learned a few things about conservation of collections. It makes sense once you think about them, but you usually don’t think about them. First is that the big enemy of most things is humidity. It tends to encourage the growth of fungus and mold. Heat doesn’t matter nearly as much. Heating in a cold climate also tends to dehumidify as does air conditioning in hot weather. Our guests told us, however, that in Brazil they sometimes still turn the air conditions off at night. It is logical. Air conditioning costs money. Nobody is around and night and it gets fairly cool anyway, so why waste the money? If heat were the problem, it isn’t much of a problem at night.

Our Brazilian friends thought they could teach Americans a thing or two about surviving crisis. When American institutions face “hard times” they might have to cut hours or slow acquisitions. Brazilian crises have sometimes meant shutting down vital functions. Yet they have adapted, improvised and sometimes even prospered. There are usual lesson that can be drawn from that experience.

Brazilian institutions are different from American ones in the extent that they are almost entirely government funded and they don’t make much use of volunteers, which are a big deal in the U.S. Smithsonian, for example, has around 6000 employees and a similar number of volunteers. And these volunteers do substantive and important work. Few American institutions could operate if their volunteers went away.

Smithsonian is an example of public-private partnership. The government funds 62% of the budget and the rest is raised from corporate or private donors. There is an important division of labor between the two sources of funding. Government funds cover buildings and basic operations, the things that you really need to make any institution function but don’t usually see or notice as long as they are working. Private funding is concentrated on the things that show. Private donors want to fund things they can see and/or things they have passion about. Nobody wants to fund search and destroy operations for fungus or bugs, but these things are crucial. The same usually goes for hidden assets like plumbing or wiring. You need something cool to attract private funders.

What the government funding essentially supplies is the box or the venue into which privately funded expositions go. It is an effective model. The U.S. has great museums and more importantly cultural instructions are spread throughout our country. One big reason this works like this is the funding mechanism I talked about above plus the fact that we DON’T have a Ministry of Culture.

Our system essentially decentralizes cultural decision making. In a county like France, which prides itself on culture, decisions are made by erudite professionals in Paris and it is no surprise that Paris is full of great cultural institution. Not so much the smaller towns. The American system distributes money and decision making power. It is the best system in our very large and diverse country. I observe that Brazil is more like the U.S. than it is like France and our experience will be useful.

Brazil often tries to be centralized but doesn’t always succeed. There are historical and cultural obstacles. Brazil, like the U.S. is just very big and then there is the drift of history. The U.S. was lucky (& leaders like Jefferson and Madison were foresighted) in that the financial & cultural center was not also the national capital. This makes it more difficult and less natural to concentrate everything in the capital. In the U.S. the most money, best brains, most important culture and political power never pools up in the same place.

America’s financial capital was in Philadelphia and then New York, never in Washington. The United States has never had a cultural center the way France does. New York, Chicago, Los Angeles and lots of others can claim to have the best of one thing or another, but none predominates, and you can find world class cultural offerings all over the place, in Milwaukee, Kansas City or Minneapolis as well as New York or Washington. Even when there are troubles, the system is strong.

Things are not so dispersed in Brazil but the principle holds. Brasília is certainly not the financial or cultural capital of Brazil. Even when the capital was in Rio de Janeiro, there was a strong rival in São Paulo and there were alternative centers in Rio Grande do Sul, Minas Gerais and Bahia. Much political power could be officially centralized in Brasília, but Brasília, like Washington but unlike Paris, Rome or even London did not have the force of its own cultural and economic gravity. This works to the benefit of a big country because it includes many more people in decisions and takes better advantage of diverse conditions and the imagination and intelligence of people all over the country.

Anyway, I believe that the contacts fostered between Smithsonian and various Brazilian friends will pay dividends for everybody involved. Knowledge is a wonderful thing. It actually increases when shared and the more of it you “consume” the more you have. We took steps in the creation of more knowledge and understanding.

My picture up top shows the model of the Museum of Tomorrow; below is rain outside the Foundation.