No pines are native to southern Brazil, but it seems to be the world’s best place to grow them. (The beautiful trees you see above in the front are “Parana pine,” but they are not a true pine.) Timber cutting is an old tradition here and most of the native forest was cleared more than a century ago and converted to pasture for livestock or large scale farming, but good forestry is relatively new.

It was only about forty years ago that a lot of people became aware of the great local potential to grow pine lumber. The first species introduced on a large scale were our own loblolly and slash pines. These were natural choices, because of their proven record in commercial forests in the SE U.S. and the many years of good silvaculture had developed around them.

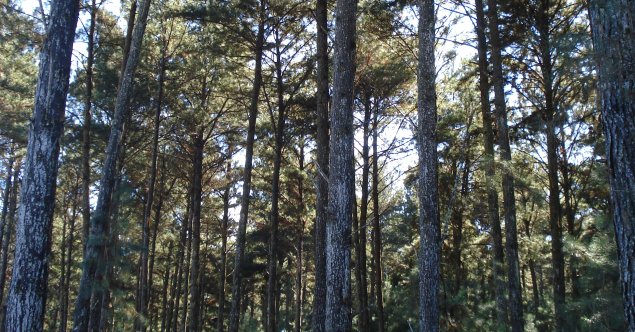

They grew even faster in Brazil, since they left most of their pests such as the southern pine beetle behind them and southern Brazil’s moist and moderate climate. The pines you see above are thireen years old and the logs below are from a thirty-two year old stand. Nevertheless, the loblolly pines I saw at Valor Florestal in Parana State were not that much bigger than similar aged pines in the U.S. Parana has other advantages, both natural and social.

An important advantage is the endless growing, harvesting and planting season. The practice in Parana is to harvest, prepare the site and plant the next generation within the same week. I saw pines planted essentially in the wake of the harvesting machines. All they do is wait for a good rain, which comes with certainty, even in the so-called dry season, and plant right after that. Below you see the clearcut in front was cut a couple days ago and is already being replanted. The trees behind are only six months old.

Site preparation consists of rolling and sometimes cutting a furrow with a plow pulled by a tractor. Renato, a forester from Valor Florestal, told me that they never use fire, almost never need herbicide and do not fertilize. The State of Parana has practically outlawed the use of fire, and Renato says that they don’t need it anyway. Natural decay is so rapid in this environment that the slash left on the ground quickly is returned to the nutrient cycle. Fertilization has so far been unnecessary, but Renato thinks that they may need to begin soon. The quick rotations are taking a lot out of the soil and they are studying biosolids and inorganic fertilizers to put it back.

There are some disadvantages to plantations in Brazil. One is rapid growth itself. Pine from southern Brazil is used in plywood, fiberboard and molding, but it is not dense enough for structural timber. Some pests attack trees. Monkeys are an unexpected problem. Those cute monkeys that you saw on “Night at the Museum” or the not so cute on “Outbreak” strip the bark off pine trees and they tend to attack the most valuable dominant individuals. Renato says that they are not sure if they eat the bark or are after the sweet tasting sap, but their activities kill trees outright or weaken them so that they are susceptible to the other local pest, a type of wood wasp. Ants are also a danger to newly planted trees. I understand that these are not the ordinary ants that we have back home, but rather a kind of industrial strength tropical variety.

Below is a 32-year old loblolly pine plantation being harvested now. It is probably the last of its kind in Parana, as they will go with shorter rotations.

I will write more later.