I read Amity Shlaes’ book “the Forgotten Man” a couple of years when it first came out, just before the big economic downturn. Her timing was excellent in the light of subsequent events and the insights for the Great Depression have been helping me understand the events of the great recession.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme, as Mark Twain quipped, and some of the arguments of the 1930s seem very contemporary indeed. One of the themes most pervasive in Shlaes’ book was the importance of confidence, consistency and trust. These things are the true basis of a prosperous economy, but they are impossible to measure accurately and so are often overlooked or downplayed.

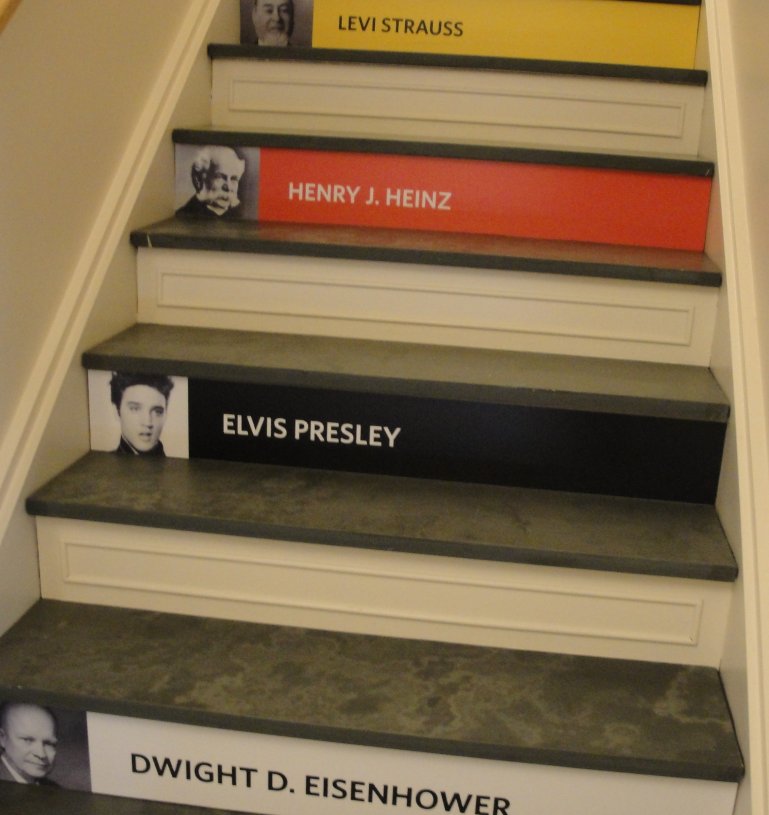

Why are you willing to exchange your real labor or goods for a piece of paper with the picture of a dead president? It is backed by nothing but trust. I lived in Brazil during a time of hyperinflation. People didn’t trust that their money would hold its value or their government not to be capricious (and they were right) so to protect themselves they had had to devise all sorts of tricks and techniques that were often wasteful and destructive to the system as a whole. And once trust breaks down in something as important as money itself, it spreads to other areas, creating a general state of uncertainly and feelings of helplessness.

One of the most important functions of government is to create as much certainty and predictability in society so that people can plan for the future and feel secure in their transactions with each other. When fails in its duty to maintain stability or, worse, when government itself comes to be viewed as unpredictable, arbitrary or capricious, the bonds of society begin to erode.

Some actually welcome this. Disorder reduces the aggregate level of wealth but often has the effect or redistributing income, or at least distributing pain since people who cannot properly plan cannot do better than those who just wouldn’t. Making opportunity generally less available tends to equalize outcomes by negating the cumulative value of hard work, talent and foresight.

What the FDR administration did to harm economic recovery was to create uncertainty, according to Shlaes. She gives many examples. The one I like best is the Schechter chicken case. Part of the New Deal legislation, regulated poultry prices, making it illegal to offer discounts or allow customers to choose their own chickens. The Schechter brothers, a couple of kosher butchers, were accused of doing these things and of “destructive price cutting.” They were found guilty, given a fine of $7424 (big money in those days) and tossed in jail for a couple months. When the full weight of Federal power can come down on kosher butchers for selling a chicken and they can get jail time for doing business as they always have, you have significant uncertainty.

The relevant New Deal Federal laws were declared unconstitutional when the case reached the Supreme Court. Justice Louis Brandeis took aside one of Roosevelt’s aides and told him, “This is the end of this business of centralization, and I want you to go back and tell the president that we’re not going to let this government centralize everything.”

Most of the New Deal programs & ideas did not survive the test of time or the courts. The reason we don’t understand that is we look back at it now with a kind of “survivor bias,” i.e. we judge it by those that did survive – a relatively small and more successful subset. But what really saved the New Deal’s reputation was the onset of World War II. To his eternal credit, Roosevelt saw the trouble on the horizon and he understood that he would have to harness the power of the United States – all of its power – to fight the threat of totalitarianism. So the always pragmatic president chucked or let fall away many of the more radical New Deal programs and much of the anti-enterprise rhetoric into the dust bin of history, much to the chagrin of his more radical associates, such as Harry Hopkins and his wife Eleanor. We kept the songs, murals, myths and lots of mixed feelings.

My father grew up during the Depression and always took a kind of pride in the fact that he could trump any contemporary hard times stories. No matter what happened, he could say, “You are lucky. When I was growing up things were a lot worse.” And he was always right. You just couldn’t argue with the old man when he played the “Great Depression card.”