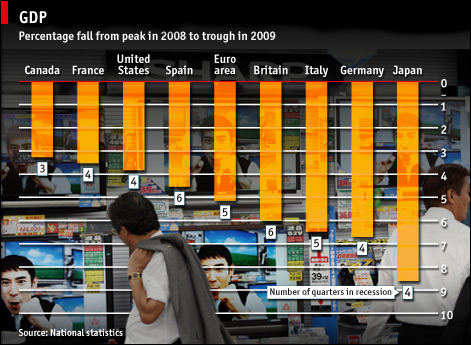

They say that misery loves company, but that is just an uncharitable way to put it. Comparisons are useful because they provide insight into problems and possible solutions. For example, you should be a lot more willing to change your habits if you see that you are doing poorly while everybody else prospers but if you are part of the larger trend learning from the experience of others might be less immediately useful. The Economist shows graphically how rich countries have fared in the recent recession.

Americans suffered in the “great recession” and it is cold comfort that Spain, Italy, Germany, Japan, the UK and the whole Euro-zone suffered more. But it should make us stop to consider the root causes of a downturn that affected a passel of countries with such a wide variety of institutions and economic programs.

The precursor the problems of the 1930s was the rapid rise of the U.S. as a creditor nation along with the circular flow of funds from Germany in the form of reparations to the allies, to the U.S. in the form of loan repayments back to Germany as loans, all the while the U.S. market was not absorbing significant imports. The great economist, John Maynard Keynes foresaw some of these problems in his “” (1919). In the 1970s, we had the problem of recycling petro-dollars after the quadrupling of oil prices in the early 1970s and further hikes around 1980. That liquidity went into loans to developing countries which soon became a problem. Recently, we had the rise of China, which has followed a neo-mercantilism strategy of selling outside while maintaining trade barriers and an artificially low currency. The dollars that pooled up in the Middle Kingdom were/are recycled into debt in the U.S. and elsewhere, helping keep interest rates low, but also helping to create a debt overhang.

The Panic of 1907, which I include only for the sake of completeness, because it spurred the creation of the Federal Reserve and because I just finished reading the book in the link, was also precipitated by rapid growth and investment in the U.S. It is unusual in that it was largely “solved” by the intervention of one individual, J Pierpont Morgan. This would be the last time that one individual was ever able to take on that role.

The Great Depression ended only with the onset of World War II, which is a fairly high price to pay to end an economic downturn. Amity Shlaes has written a good book called “The Forgotten Man” that details some of the policy fits and starts that did not alleviate the depression and may have deepened it. The end of the recession of 1982 is still way to close to be dispassionately assessed. We forget how bad that one was. Unemployment reached 10.8% but it soon eased and we had a quarter century of decent economic growth punctuated by two short recessions.

We don’t know what will bring us back to prosperity this time, but I have confidence that we will recover. We always do.If you look back at history in the last century, it seems we have a painful downturn every twenty-five years or so. The times of trouble last for around ten years (except in the 1907 case). Let’s hope this one will be shorter. But since nobody has been able to “predict” even the past accurately, I don’t have a lot of confidence in anybody’s ability to predict the economic future.