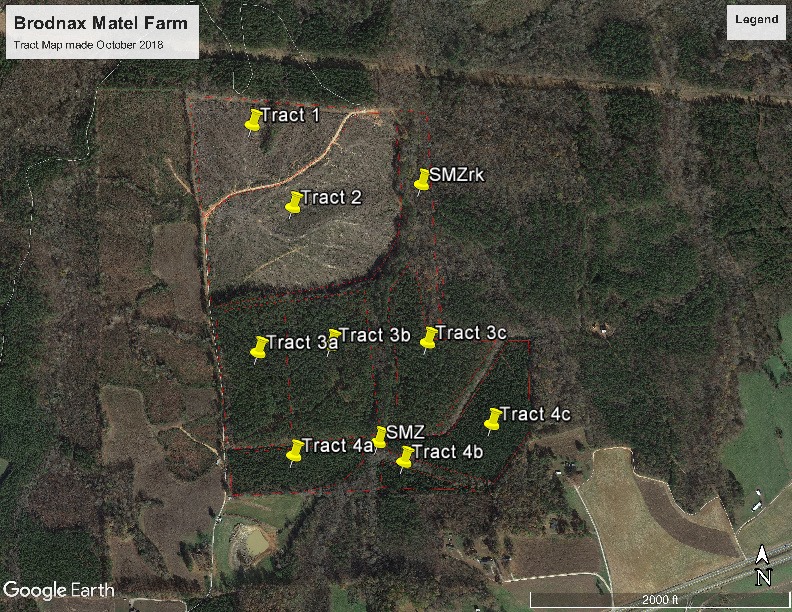

Everything I can do, Bill Owens can do better, at least when we are talking about longleaf pine in Virginia. This is all to the good, since we all benefit from the good works of others. Bill has a lot more acreage in general, a lot more acreage in longleaf (his land comprises around 20% of ALL Virginia longleaf on private land) and yesterday I attended a program commemorating his committing more than 1500 acres to stewardship for the Nature Conservancy.

Fire in the forest can be good

We started with a field demonstration of fire in longleaf forests. People who know me are bored when I say it, but I need to repeat anyway. Longleaf is a fire dependent species. The first English colonists found vast and generally wide-open forests of longleaf. Judging from the remnants we see today, they were forests of remarkable beauty and diversity. They harvested the big trees. This was our founding forest, the forests that first built what became the United States of America. Trees are a renewable resource, but the colonists did a couple things that prevented regeneration of longleaf forests – they introduced free-range pigs that rooting up longleaf seedlings (the pigs especially liked the longleaf because of their bigger roots) and they excluded fire. They just didn’t understand.

Fire was a regular feature in pre-settlement Virginia pinelands. Some were set off by lighting, more often it was Native Americans who set fires. Virginia was not a wilderness. It was a landscape managed by humans, with fire as their most potent tool. Fire passed through Virginia pine forests every 3-5 years, more frequently in some other areas of the south. These were low intensity fires, surface fires that pruned the lower branches but did not reach into the crowns, as you see in my first picture. They burned brush and litter, but rarely killed mature trees. This was an ecologically beneficial fire (not like those we read about in California that result from poor land management, but that is a different story.)

Bringing fire back

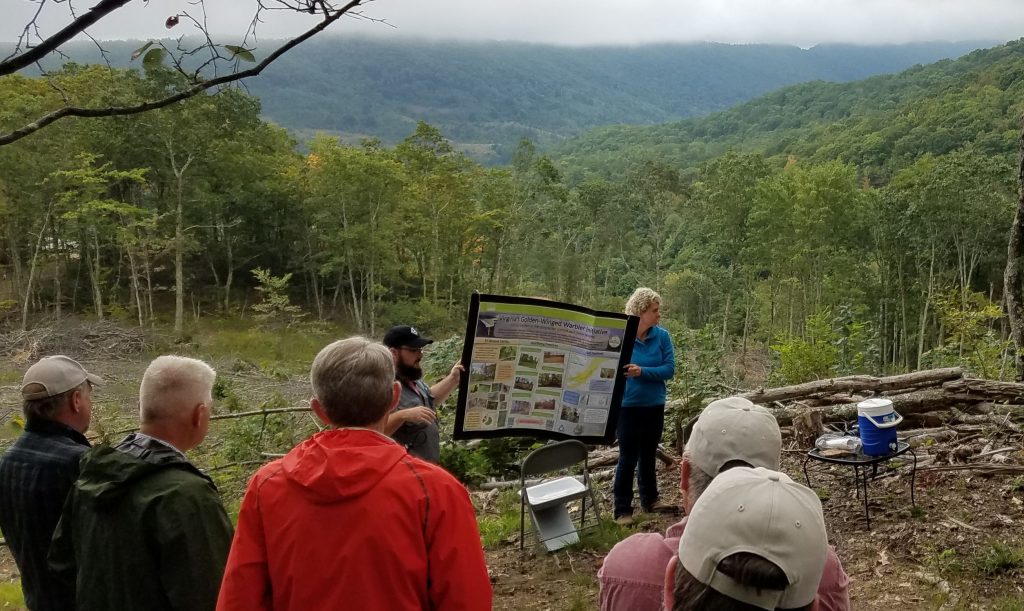

Virginia Department of Forestry, US Fish and Wildlife, TNC, Longleaf Alliance, NRCS and lots of private landowners, me among them, are trying to reintroduce ecologically beneficial fire to the commonwealth. It a deeply cooperative endeavor.

The ecological benefits of fire are obvious to scientists who study fire and practitioners who use it to improve forest health and wildlife habitat, but setting the woods on fire is not an easy sell to a general public that grew up with Smokey Bear’s messages and images of fire destroying forests and homes. As I am writing this, I am listening to reports of dangerous fires in California. Fire is the enemy, according to most people. If nothing else, they dislike the smoke and disturbance. To this there are two responses.

— Re the problems of fire – fire is an unavoidable and natural part of nature. If we do not choose a good time to set off the fire, nature will give it to us in the worst times. And if we exclude small fires, we will get big ones. This is history and the present, as we hear about every year.

–Re disturbing nature – nature is always disturbed. It is how nature works, always becoming never arriving. We call that natural change. Embrace impermanence. It must be welcomed. We can benefit if we understand and flow with natural processes. We can multiply our choices working with nature or we can be dragged painfully along in ignorance & against our will. In either case, we are going.

You can tell which I advocate. Living within natural processes brings freedom and contentment. Fighting them brings frustration and ruin. A life spent trying to understand, or maybe perceive natural processes in meaningful. But I am drifting from my story.

Returning to the Owen story

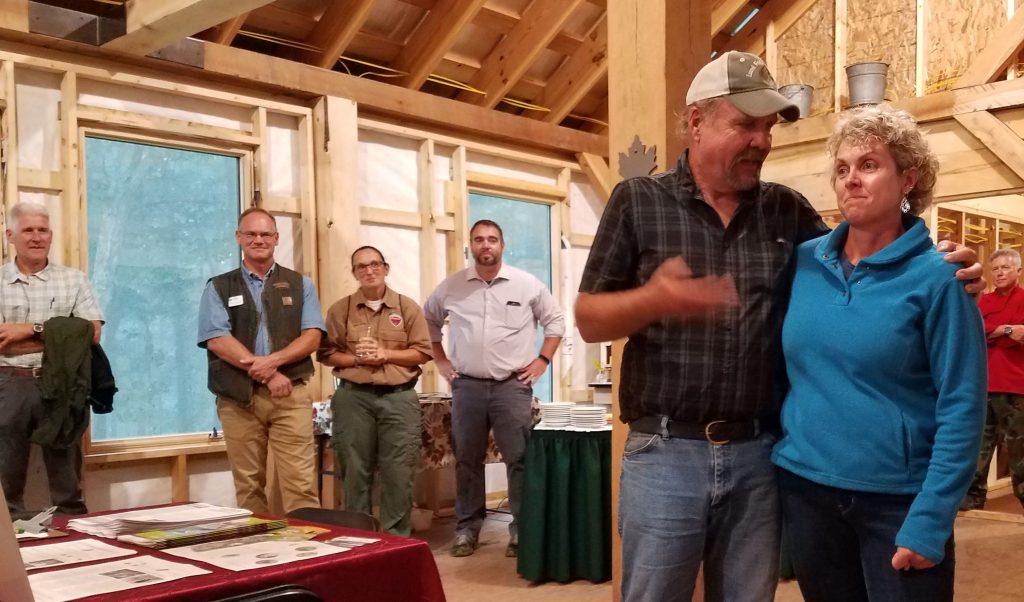

Bill Owen’s generosity was commemorated with a reception at the Petersburg Country Club. Among the speakers were Reese Thompson from Longleaf Alliance. He is the one who “invented” Burner Bob, a giant bobwhite quail that promotes prescribed fire in the forests the way Smokey Bear told us to avoid wildfire. Bettina Ring, Virginia Secretary of Agriculture and Forestry and previous Virginia State Forester. She pointed out that agriculture is Virginia’s leading industry and forestry is number three, after tourism. Brian Van Eerden from TNC opened and closed the ceremony.

My first picture shows the fire in the forest. Next is what it looks like unburned for only a little more than a year. The stuff accumulates. Picture #3 is me and Burner Bob, followed by NRCS and TNC explaining longleaf ecology and programs available to landowners. Next is the ceremony at Petersburg Country Club. The penultimate picture shows a special longleaf beer and the final picture shows some of my bald cypress on the Freeman place. They are easy to see with their fall colors. I have trimmed around them so that they will not be killed by the fire we plan for this winter.