Facebook post

My last photos of the day. There are live oaks and Spanish moss from the Nemours plantation. The last photo is a tuft of little blue-stem grass, a warm season grass common in southern pine savannas, well … common in lots of places around North America.

The Nemours Plantation 1

The Nemours Plantation was part of the rice growing complex in the ACE basin, called that after the three rivers – Ashepoo, Combahee and Edisto – that make up one of the largest undeveloped estuaries along the Atlantic Coast. Rice production became unprofitable in the late 19th Century and much of the population left. Rich industrialists from the north bought up lots of the land for hunting preserves, among them the Duponts, who bought what became Nemours. Much of the rest reverted to forests.

The rice growers had impounded the waters by building dikes with contraptions that allowed water to come in at high tide and then prevented it draining at low tide. Although the rivers were tidal, the water if fresh. High tide merely caused the river water to back up. My pictures show the devices used to hold the water. You can see how it works in the model. Workers open the gate when the tide is coming in and the receding tide seals it. The design was Dutch, people who had a lot of experience with dikes.

When the hunting estates were formed, they converted the rice impediments to plants to feed migratory birds. They still are doing that job. Recent heavy rain and wind of Hurricane Matthew breached many of the dykes. One of my photos shows repairs underway. You can also see the gates and a model that shows how it works. The other two photos show downed trees. You can tell if a forest has not been cut for a long time by, among other things, the humps and holes caused by roots pulling up the dirt. A cleared and plowed field smooths out these things.

Drones

Drones will change how we do forestry, or at least how we see (literally) our forests. We saw a demonstration of a drone today. It was smaller than I thought (they do come in bigger sizes) and quieter. It sounded like a bunch of bees when it was close; you could not hear much at all when it got higher up.

I will wait a little while before getting one. I figure the prices will come down as technology improves. As I get older, it will be useful way to keep up with the land. If I also get one of those little all wheel drive vehicles, I will have it made.

The first three pictures show the drone. The last one is a pine savanna. It is mostly loblolly and not longleaf, but has many of the same characteristics. They created it from a thickly planted plantation and now maintain it with fire and herbicides.

Longleaf conference in Georgia

Note from 2019 – On this trip I developed an aneurysm in back of my knee. It was a serious problem. In Georgia, it was hard for me to walk. I only later learned what it was. The doctor said that I could have surgery or try to exercise through it. I chose the latter, but worried that I would never recover, might even die from that artery disease. So far, I have mostly overcome the problem. Mostly.

I saw less of Savannah than I could have/should have because it was so hard to walk. I regret.

Driving across the Carolinas

Crossed into South Carolina. Gas is about twenty cents cheaper just south of the border. I got to the station ahead of news of the pipeline accident in Alabama. I expect gas prices to spike up.

I know there is lots of sympathy for those opposing the pipeline in Dakota. I can understand. But as long as we use fuel, we have to move it. Pipelines are usually the most efficient way to do it. We see the dire consequences of a pipeline being disrupted. If they were not built in the first place, these higher prices would just be normal. Meanwhile, fuel would still move, but by road and rail, adding cost, danger and ecological damage.

It would be great if there was really a unicorn option.

Speaking of transport … my other photos are from the Savannah River in front of my hotel. Containerized cargo changed the way we move goods and that innovation is largely responsible for this stage of globalization.

The call it Intermodal freight transport. Those containers can be easily loaded, unloaded and transferred to trucks or trains with less effort, loss, waste or threat. Our world underwent a significant revolution in the 1970s and 1980s and we didn’t really notice.

Most real change is like that. It creeps up on little cat’s feet, silently, until we notice it suddenly and think it just happened all at once.

Savannah Georgia

Have not yet seen too much of Savannah, but what I have seen is interesting. This is where they filmed “Forrest Gump” and the Gump bench is a minor tourist attraction. I will walk up and see it.

In the meantime, I have been close to the hotel admiring the live oak and the Spanish moss. Of course, Spanish moss is neither moss nor from Spain. It is a flowing plant that absorbs what it needs from the air. That is why it requires climates that are generally warm and usually humid. Savannah is like that. The Spanish moss rarely hurts the tree that host it, unless it grows in such perfusion that it shades out the leaves.

Poetry

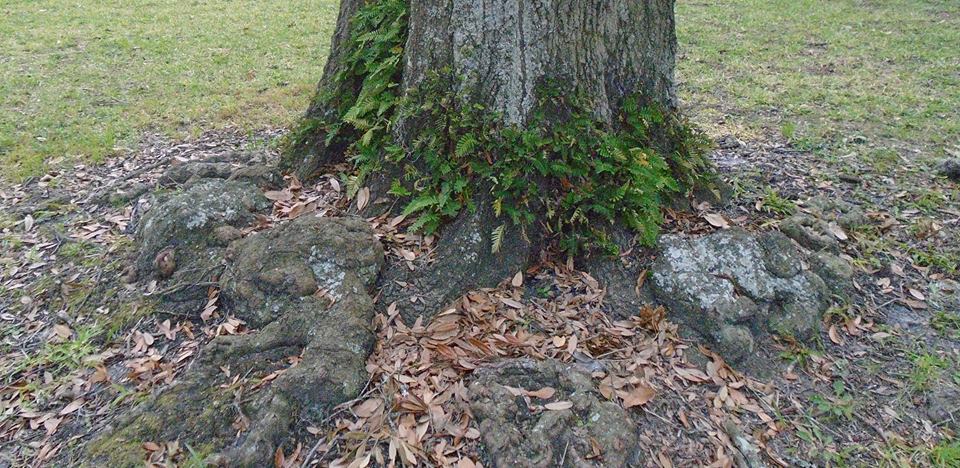

Last post for today. We used to have to memorize lines of poetry. It seemed a waste of time and it was, from some points of view. There are no poems that I can really recite w/o lots of mistakes. But I do recall the general lines of many. One such is “Flower in a crannied wall” by Alfred Lord Tennyson. The lines I vaguely recalled from Miss Ryan’s 12th grade English class at Bay View HS came bouncing back when I looked at a wall with ferns and flowers growing out of the cracks and crannies. The other photos show a bald cypress grove and ferns growing in and on the roots of a live oak. Below is Tennyson’s poem.

FLOWER in the crannied wall,

I pluck you out of the crannies,

I hold you here, root and all, in my hand,

Little flower—but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is.

Southern grasslands … with trees

Facebook link

Learned and relearned some interesting things at the longleaf pine meeting. The keynote speaker was Reed Noss, who wrote a book that I bought (but admit I have not yet read) called “Forgotten Grasslands of the South.” He understands the longleaf pine ecosystem as much as a grassland as a forest and his point have merit. A natural longleaf ecosystem is a savanna, which is a bit of both and neither.

It stayed a savanna because of fire and grazing. If you exclude fire and grazing animals from an acre of land in the Southeast, it turns to thick forest in short order.

Noss referred the longleaf ecosystem as fire DEPENDENT. This is a slight difference from fire adapted. The fire dependent ecosystem does not exist in spite of fire but because of it. When fire is excluded, it dies.

The longleaf ecology is one of the oldest and most diverse in North America. Something like it originated Oligocene 33 million years ago and maybe in the Eocene more than 50 million years ago. It was not exactly like the pine today, but fossil record indicates it had similar services. (Note that paleontologists can recognize pine pollen, which they take from lake bottoms and they can generally tell northern from southern pine species, but cannot be more precise than that.) North America changed many times, of course. For part of the time the “coastal” plain was up around what is now Kentucky and Tennessee because of higher sea levels. At other times it was well into what is now the Gulf of Mexico from lower sea levels. What is certainly the longleaf pine biome is much more recent, after the last ice age, maybe 5-7000 years ago.

You have to think of the pine ecosystem like a pulse. It extends out or in depending on the changing climate conditions. North America has been much warmer than it is today and much colder, so the area adapted to southern pine is not the same.

Fire dependent pine species have two main strategies. Some, like jack pines or lodge pole pines, burn up entirely. Their cones will not open until they are burned and the progeny quickly recolonize burned over places. They need big, hot, crown fires. Others, such as longleaf and shortleaf, adapt by being fire resistant in their seedling stages and then develop thick bark to resist flames when they are older. They depends on frequent but not very hot surface fires. W/o fires they will disappear, out-competed by other species.

There is disagreement about when to burn. Foresters like to burn in winter because it is safer with cooler temperatures. This is not natural, however. Paleontological evidence indicates that fires were most common in May and June, when there were lightning strikes but before it rained very much. A winter fire does not kill hardwoods, while a growing season fire does and encourages grass and forbes.

Because of fire, not in spite of it, the southern pine ecosystem is one of the worlds most diverse. It is a global biodiversity hot spot that we need to work to maintain, using fire and grazing … and planting more longleaf.

At one time longleaf dominated 90 million acres of land in the south. It was down to about 3. We have brought it back to 4.5. We are planting 110 million longleaf pine seedlings every year and hope to cover 8 million acres with longleaf by 2025. We will not be able to restore it to its former glory, but we are making a good start.

Pine Straw

Facebook link

I feel a little churlish complaining about a place where I was a guest, but I do not like this sort of forestry. Pine needles, mostly from longleaf, are used as garden ground cover. Raking and selling needles can be a lucrative business for forest owners.

But there is a cost. The needles need to be clean, i.e. not a lot of sticks, cones or generally anything that is not needles. The nature of raking also means the forest floor needs to be smooth, and raking takes nutrients out of the forest and stresses the trees.

The key reason I favor longleaf pine and am trying to establish longleaf on some of my land is because the longleaf ecology is so beautifully diverse.

The land ethic informs the way I think forest land should be managed. Those things that enhance the health and sustainability of the biotic community are good. We can and should profit from our land, but there is more to it.

Look at my pictures and tell me what you see. Sure, there are longleaf pine, but it is not a healthy and diverse longleaf pine ecology. It reminds me of a warehouse with stuff swept into the middle.

I understand that people should be able to make choices about their land. I also know that those choices can be better or worse. I will not be harvesting needles on any of my land. I love the complexity of the changing face of my land and I take joy in the the things that I do not control. A forest is more than the trees, wood and pine straw.

October farms visit

Went down to the farms today and took a few photos, probably that last of this growing season. Alex came along. We spent a lot of time cutting vines.

My first photo shows a couple of my bigger longleaf pines. They were planted in 2012. I am 6’1”, so these look to be around 15 feet high. One reason why some people prefer lobolly to longleaf is that loblolly are more consistent. You can see in my next picture that longleaf is variable. Some are fifteen feet tall and others are still less than a foot tall. Most are around 6-9 feet high.

Photo #3 shows the loblolly planted in 1996. The little figure in the front is me, for comparison. Picture # 4 shows some of the vines, makes it look like a ghost forest. We have been cutting them. Most of the trees are not as affected as those in the photos. Those are 2003 loblolly. The last photo shows that fall in coming. This is from the Brodnax place, looking over the place that was clearcut last year. The little trees we planted this year are there, but they are hard to see.

My quarterly contribution to "Virginia Forests" magazine

Forests are changing and so is who owns them

If it seems like forest land ownership is dominated by people at or near retirement, that is because it is. While most Virginia landowners are 45-65 years old and only about a third of are over sixty-five, the older group owns around half of all forest land. This creates anxiety. That is why you find articles related to estate and succession planning in this “Virginia Forests “magazine. I am not here to tell you that this is not important, because truly it is. We are planting for the next generation; we need to plan for them too.

The advancing age of so many forest owners, however, is not surprising. Some owners inherit land. Others buy it as a long-term investment and from passion for forestry. At what stage of life is this most likely? Forest owner are often older individuals the same way HS seniors are usually around eighteen-years-old.

Forest are always becoming. This is true of what is growing on the land and who owns it. It is not profound wisdom to say that the future will differ from the past and that it is hard to predict. We can, however, predict with confidence a big trend already in process. Forest ownership is becoming more fragmented, with more owners and smaller acreage.

Remember I said that the over sixty-five age group makes up a third of forest owners but owns half of the forest land? Newer owners own less acreage on average. Most (84%) have purchased their land, i.e. did not get it through inheritance or gift. They are the future. The smaller the parcel the less likely owners are able to practice forestry consistently. Less managements can be done on ten acres than 100, for example, and it is often hard even to find someone willing to harvest small tracts. Implications for forestry and forests are significant. Forest fragmentation continues. We need to develop strategies to address what we cannot avoid. Possible actions include things like encouraging groups of landowners to cooperate in forest management and making information more readily available to a mass-market of owners.

Tree Farm’s strength has been personal contact to understand landowner specific conditions and needs and provide customized advice. This worked for seventy-five years, but is not practical when the number of forest owners goes up as acreage goes down. Tree Farm protected water, soil and wildlife. More trees are growing in Virginia today. But we need to engage a wider range of people. We may lose the personal boots-on-the-ground truth, but smaller-acreage tree farmers can still be deeply engaged, maybe sharing knowledge laterally within the tree farm community. Many bought land because with passion for forests and desire to be part of sustainable forestry. We share aspirations. Together can achieve great things – IF we make and sustain community.

Sustainability does not mean unchanging. It is beneficial change that nourishes the health of the land and the biotic and human communities on it. Tree Farm has done a great job of helping sustain communities and can do it into the future.

Visiting clear cut in Brunswick County

Inspected the place we clear cut last year. It is now fall, so I can see what is coming under. We planted 21,000 seedlings in March and April, almost 500 per acre. It looks like there will be a lot more. The loblolly have seeded in. The reason we planted, as opposed to natural regeneration, is that I think that the new seedlings will be genetically faster and better. I guess this will be a good test case. Presumably, I will be able to tell in five years.

My first photo shows the loblolly that have grown in the last few months. Next shows how much they have filled in in the landing zone. Picture #3 is some of the older loblolly, maybe the seed sources. The last two photos are shortleaf pine. These are also beautiful trees. They grow slower than lobolly and in many ways behave more like a hardwood species. They are the most widespread of all southern pine species, but are always associated and never dominant.

GMOs

I would like to see some of this applied to forestry. The leading ecological threats today are invasive species and native species made functionally invasive by environmental change. We have seen near total destruction of the American chestnut, which once made up around 1/3 of the eastern forest. We are experiencing oak wilt, hemlock investigation, emerald ash borers, scale insects on white pine … I could go on with the depressing litany, but suffice it to say that there is no possibility of cultivating forests on a large scale the way farmers can do fields.

If we are going to save our forests, we need all the tools, including GMOs. We would not introduce them forest wide. What about something that did to the ash borer what the GT corn does to the corn borer? It takes a long time in forestry, so we need to start yesterday. I do not expect a panacea, but in the Anthropocene, GMOs are a key tool in maintaining ecological diversity of our forests.

Reference – http://www.wsj.com/articles/gmos-are-a-necessityfor-farmers-and-the-environment-1475537025