Our Information Section did something really great with social media. I find it almost unbelievable. It came, as many things do, at the intersection of preparation and changing conditions, with a little bit of luck. Let me explain.

We launched our 9/11 commemoration campaign a couple days ago. Our theme is “superacão” or resilience & overcoming difficulties. My colleagues prepared a poster show. We did some media interviews & generally reached out to Brazilian media and people. There is no shortage of attention to 9/11 in Brazil. We don’t have to create a demand. But we do prefer that the narrative be one of superacão and resilience rather than destruction. We want to remember and honor the victims, but emphasize the resilience of America.

Among the things I find most appealing is a program we have set for September 12. Ten years ago, after the attacks of 9/11, a school in Ceilândia, just outside Brasilia, made an American flag for us. All the students contributed part. It was very touching and we still have their work. We will return to the school for a ceremony and have invited the original students, now young adults, and their teachers to join us. Response has been great and I look forward to taking part. But I am drifting. Let’s return to social media.

We launched the campaign this weekend and as of this writing we have more than 106,000 responses. We might have had a few more, but the initial surge crashed our server and we had move to a bigger server. Our theme of superacão was popular with our audiences. They were invited to write their own feelings about 9/11 and/or their own stories of superacão. And they did. Our Facebook page has almost 10,000 new members and we have gained another 38,000+ on our Orkut platform. Orkut is popular with non-elite audiences in Brazil. A video of Ambassador Thomas Shannon talking about 9/11 has garnered 9,260 views as of this morning, but I figure more than 8000 by the time you read this. Today we were getting almost 1000 new comments every hour. I say comments, not visitors and not “hits”. A commenter has to take the time to write something.

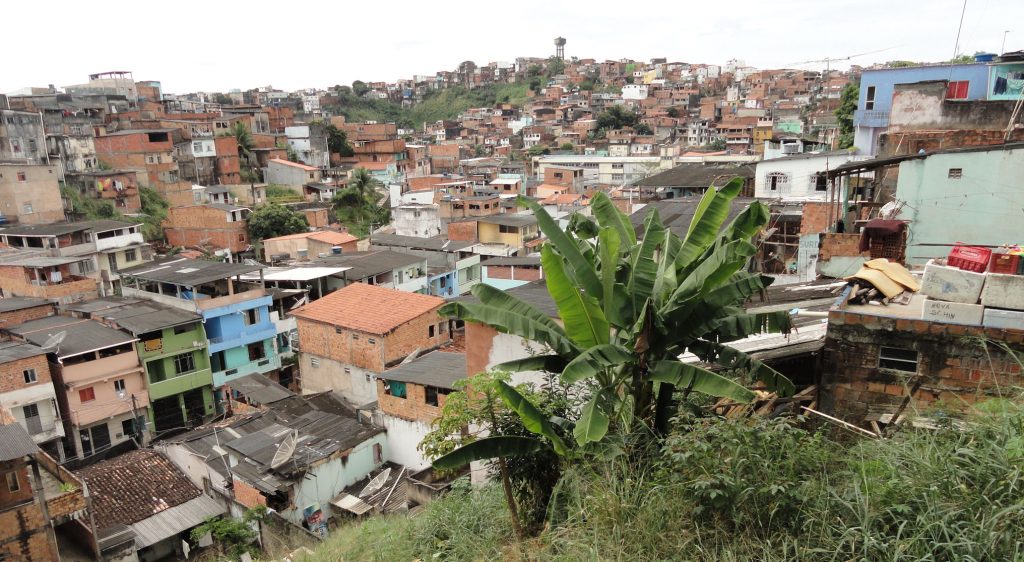

Our initial demographic analysis indicates that participants are coming to us from all over Brazil, even interior towns indicating that Internet has penetrated far into Brazil. Many of our participants are from the less-privileged social groups. This is because the Orkut component is providing them a forum, we believe.

I want to emphasize again that these are responses, not mere “liking”. Of course, we have been unable to look at all 100,000+ responses, but our sampling indicates that most are thoughtful. Most are also favorable to the U.S. Many of the personal stories of resilience are moving.

We will follow up with social media and with boots on the ground. I remain a little skeptical of social media that doesn’t yield physically tangible results. One of our initial ideas is to take representative groups from various cities and invite them to programs or representational events when we visit their home towns. This will create a good media opportunity both in MSM and new media, especially in those places were we rarely tread. It makes it more concrete and exciting for the participants and fits in well with our plant to reach out to the “other Brazil”, i.e. those places not Rio, São Paulo or Brasilia. As I wrote earlier, we had planned to reach to the 50 largest cities. I had to add a few extra so that we could encompass all state capitals, even in places with thin populations and some cities of special significance, such as an especially good university, for example. I ended up with 61, but I think I will find five more so that I can call the plan “Route 66”.

I don’t know how many Brazilians we will have touched by the time we are done with this campaign, but I think we are doing okay so far. As I have written on many occasions, this is a great place to work. The only problem is that we might get tired taking advantage of all the opportunities.

Up top I mentioned the intersection of preparation, good luck and changing conditions. Preparation is what my colleagues did and have been doing. They built a social media system ready to be used. It needed an opportunity. They also prepared for what they knew would be a big anniversary. But this program would have gone nowhere had not Brazil expanded its internet network, so that people could respond. I don’t think this success could have happened last year or even six months ago. One of the Portuguese terms I learned was “banda larga”. It means broadband. Many Brazilians were learning the term and its meaning the same time I was. Now they have the capacity to log in and they are doing it. New fast-spreading technologies have allowed Brazilians to jump over a digital divide that we thought was as wide as the Grand Canyon. We are lucky to have these conditions.