I give up. For many years I have been looking for a grand unified theory of persuasion or at least of public affairs. I have read hundreds of books about the subject and thousands of articles. I have listened carefully to skilled practitioners and tried a lot of things out for myself. I have achieved success, suffered failure and tried to apply the lessons of each. I have looked for the pattern; inferred the pattern and imposed a pattern where none really existed. But the long search has reached a dead end … and an insight. (The owl of Minerva flies only at dusk.)

Below is the Library of Congress. There are several other buildings which together contain the accumulated knowledge of humanity. All you have to do is look for it.

I could not find a grand unified theory of persuasion and public affairs because none exists. I have to be content with tactical success and experimentation. The best strategy is to follow up and double down where things work and abandon failure as quickly and cleanly as possible.

An organization that can do this is not omniscient; it is robust and opportunistic. In an uncertain world, we are always playing the probabilities. It is a world where the best plan might fail and the worst succeed, but in the course of repeated tries and many actions, the better ones make progress. It is an evolutionary system that unfolds through iterations; the truth is revealed conditionally and gradually. It cannot be choreographed in advance.

I remain a believer in truth and in seeking truth. It is just that I do not believe that we humans have the capacity to find the big truths. Actually, I am not giving up the search, but I am switching methods. Repeated inquiry and intelligent analysis of both process and results will bring us to an approximation of practical truth, wrong in many details but useful for decision making in the situations for which it was developed.

You don’t need to know the whole truth to know what to do. We have to walk the line between recklessness and paralysis. At some point we know enough to jump. That point comes when we estimate the probabilities are good enough – not perfect, but good enough – when the probable outcome of doing something is better than waiting. We will be wrong a lot. We need to be robust because omniscience, or even understanding most things, is not an option available to mortal man. We are always wrong to some extent.

“Often wrong, but never in doubt.”

That is how they described MBAs when I was at the University of Minnesota B-school. It was meant pejoratively, but it is not a bad strategy. If you more likely to be right than wrong and the rewards of success are significant while the cost of failure is not catastrophic, the smart decision is just do it. If it works, do it again and improve it. If it doesn’t work, figure out why and do something better.

Just because you don’t have a detailed plan doesn’t mean you don’t have a plan. Often the best plan is the structure of the choice architecture in the organization itself. Giving people a broad goal in an organization structured to take advantage of opportunity and can learn from experience is the best plan you can have in a changing world. After it works, you can take credit for prescience if taking credit is important to you.

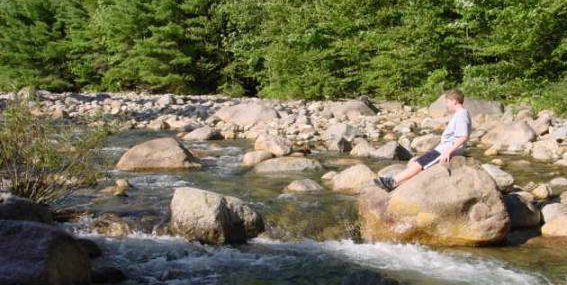

Ask the guy in the kayak about his precise plan before he hits the white water around the bend. It is better to know you can adapt to what will come than to develop a bogus detailed strategy for everything that could be on the way.