Below – the urban forestry meeting was held at the Fairfax County government center. Fairfax is the biggest and most populous county in Virginia. I was told that there are still some farms in the county, but I have not seen them. There are a lot of forested acres, however, both in private and public hands. I heard that the Fairfax School System plans to plant trees on some of their mowed places. This is good for the environment and saves on maintenance costs.

BTW – if you want to attend these sort of events and learn re forestry in Virginia, the best information aggregator is the Virginia Forest Landowner Update.

Urban forestry meetings attract a consistent demographic divided into two parts. The first segment is at or near retirement with time to pursue their interests unpaid. I guess this is where I fit in. Then there are the professional “tree people,” those involved with forestry, landscaping or local government make up the second group. There is essentially no ethnic diversity. Everybody looks like they walked out of a 1950 LL Bean catalogue. This may become a problem. A good part of Northern Virginia’s tree cover depends on the volunteer efforts of local citizens. Trees are too important to be the concern only of the dwindling LL Bean demographic. I have noticed, however, that the age ratios have remained consistent over time. Maybe people just don’t get interested in these sorts of things until they reach a certain stage of life and maybe this problem is not a problem.

I am interested in forests but many of my fellow attendees seem more interested in trees. These are not the same concerns. Some of my colleagues personify individual trees. I agree that some extraordinary trees need special protection, but the forest trumps individual trees and forest health depends on cutting some trees. Somebody even used the term “tree-rescue” in referring to moving trees from a place being cleared for a highway interchange. This implies another “rights mindset,” and a fundamentally anti-ecology theology.

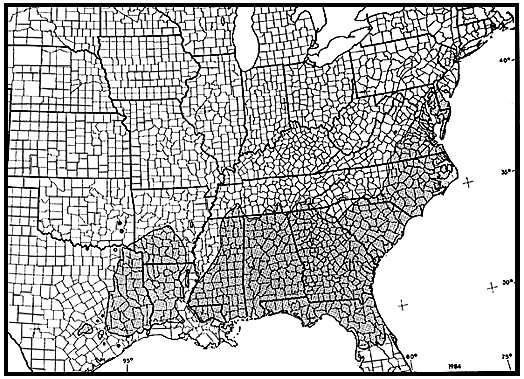

Below is the natural range of the loblolly pine range. The range extends as far as New Jersey and the tree can survive if planted farther north, it is essentially a south-eastern species.

The Rappahannock River is roughly the boundary between Northern & Southern Virginia both culturally and ecologically. I have a foot in both regions, since I live in Northern Virginia, but my forest is in the South. In suburban Northern Virginia, a few acres or a couple of trees are a big deal. Down in Brunswick County foresters don’t pay much attention to anything less than forty acres. In the Virginia suburbs, trees are usually seen as part of a garden landscape. In the in Southern Virginia they are timber in a forest. In the North, tree lovers look toward the Middle Atlantic States. South of the Rappahannock, where the southern pine forest ecosystem starts and then stretches to the Gulf of Mexico, it is natural to look toward the Carolinas. There was a little grumbling at the meeting that southern forest interests kept Virginia in the U.S. Forest Service’s Southern District, but I think that is where we belong from the forestry point of view.

Some people at the meeting really hate English ivy and often voice their feelings. They want it declared a noxious week and banned, and evidently tried w/o success to get the State of Virginia to do that. I understand that English ivy could be characterized as an invasive, but it is not that hard to control and it serves useful purposes. For example, nothing that I see around here holds soil better in ditches, since the plant can root in the firm soil and form a network of vines in the erodible dirt on the sides and in the bottom. This is especially true near paved roads and driveways. When people advocate ripping out ivy, they do not provide real solutions. Sure, native plants might be better (although I am unenthusiastic about poison ivy), but they won’t grow in the disturbed conditions and soil structures that human activity creates. It is just dreamy to think we can – or will – create and sustain the conditions that will allow the beautiful native diversity we would all want in theory. We need solutions we can actually live with. You can use Virginia creeper or wild grape, but those tend to climb into the canopies worse than English ivy does. Those vine covered trees we see along the Metro line and along I-66 are being harmed and killed by native vines. English ivy in many cases may be the best obtainable solution.

Besides, it is pretty and well-suited to the area around Washington. I don’t feel bad about the English ivy. It also seems to displace poison ivy, which is a native plant but it provokes rashes in about 80% of the population. Native is not always better.