The good news is that cable television has resulted in a proliferation of good programs about science, history and politics. If a picture is worth a thousand words, lots of moving pictures must be worth millions of words, but the pictures may be out of context and if you count up the total number of actual words in an hour on History Channel, you could probably fill only a couple of pages. (Re pictures – I watched “the Real Abraham Lincoln.” It featured a reenactment of the young Abe. But the guy has a beard. Lincoln didn’t grow the beard until 1860.) TV spends a lot of time repeating scenes of collapsing buildings, burning fires or horsemen galloping, w/o explaining the significance. The shallowness of the medium is the bad news.

This extends beyond the series of gripping but unenlightening images. I also notice a general decline in rigor. Maybe it is a general phenomenon, but you notice it clearly on TV. Instead of trying to evaluate evidence and sources, the programs sort of throw it all out there with equal credibility. This would be okay with a written source or among scholars, but the television images don’t provide enough background or references for the viewers to evaluate veracity, even assuming most audience members had the background or inclination to do so.

It is bad enough when we have dueling “experts” but it gets worse when many programs seem to put oral histories on par with real ones. All histories are subject to interpretation and just because something is written down does not mean that it is true. But oral history must be even more carefully evaluated because it is literally subject to change w/o notice.

The strength of written sources is that they freeze impressions and the facts at the point of writing. Facts don’t improve with age. An earlier recollection is more factual than a later one and a primary account is better than a secondary one. An investigator can compare a written record against subsequent ones to detect enhancements or omissions. It makes it harder to change the story. It is also possible to nail down the assertion, so that you can check them against other evidence.

Oral histories do not suffer these constraints. When confronted with disconfirming evidence, an oral history can just change. The danger to the integrity of the story comes not only from deception, but also from innocent rationalization. People tend to want to fit their stories into current realities. They smooth the edges to make them conform to the present needs.

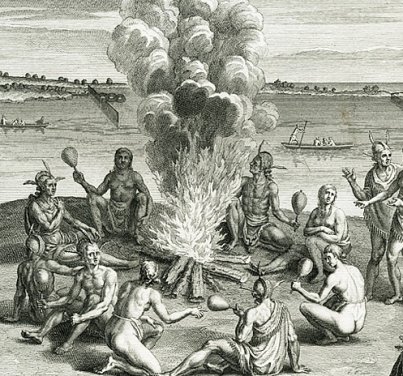

This story changing is most often a social process. Stories change in the telling and retelling and in a short time they come to reflect the aspirations, interests, prejudices & desires of the group more than reality. Oral history has great value because it tells you a lot about the people telling the story; it tells you less about the actual historical events on which is it ostensibly based. It has to be handled carefully.

Of course all history starts off as oral. It is the raw material. Beer starts off as barley and hops, but it requires some processing before you drink it. The same goes for oral history. If you take oral history from those who actually experienced an event, you can check facts. It is helpful to compare stories of individuals who have not communicated with each other much since the events in question. It gets harder when you get into the second or third generation of the story. At that point it has probably become myth. It may be based on the truth but it is not truth.

Myth is usually more interesting and plausible than actual historical events. Heroes are stronger and braver. Villains are scarier. Causes are more just. Events make more sense and often presage big developments of the future. They make better narratives precisely because they have been edited and enhanced by the people who have told and retold the stories.

The compelling nature of oral history and the resulting myths makes them especially dangerous on history television. They are almost always more interesting and more easily recreated in dramatic reenactments. It gets worse in our PC world. Many historical programs these days portray the confrontation between literate and pre-literate societies. The literate societies have historical records that can be critically evaluated and parsed. You get the warts and all portraits. Given the critical nature of this inquiry, we often end up with a mostly warts portrait. On the other side, we have the myths property altered in light of subsequent events.

Below are Alex and Chrissy at “America’s Stonehenge” in New Hampshire. We visited it when we lived nearby in Londonderry. It is worth seeing but not worth going to see. The History Channel featured it as a “mystery”. It is a mystery – a mystery why some clown would pile those rocks, but otherwise it is clearly not ancient. But a TV show with lots of cool angles and suppositions can make it seem so.

Modern historians are understandably frustrated. They want to write about pre-literate societies and they want to write about conditions of the common people in all past worlds. Unfortunately, pre-literate people don’t write at all and the common people didn’t write much until recently. I don’t know a precise number, but I doubt that more than 5% of all the ancient Roman texts still exist, so we start out with a small sample. None of the authors are representative of their societies, in that most people couldn’t write, so you already have an elite enterprise. There are no significant female historians from the Roman period and the Romans were unenthusiastic about letting their subject people write critical accounts of their rule. Beyond all that, most the writers were not interested in the doings of the common people, male or female, Roman or not. When the sturdy yeomen are featured, it is usually just a didactic example. Victor Davis Hanson wrote a good book on people working the land, who always made up the vast majority of the population, called “The Other Greeks,” but there just are not many good sources. You can learn a lot about physical conditions from archeology, but you still don’t have the narrative. The stones and bones don’t tell you much about the people’s motivations, imagination or aspiration. That is unsatisfying. Imagine if a future archeologist could reconstruct your television set but had no record of any of the programs. So historians extrapolate and move the historical narrative into the realm of conjecture, as with other forms of oral history telling us as much about the extrapolator than about the subject itself.

All the specialty cable channels (history, discovery, military, science etc) are spreading information wider than ever before. That is good … I guess.

Particular parts of the programming that I think is very good are some of the “current” history features. I have seen several good programs on Iraq. They tell the story and interview the people involved. My belief is that the U.S. public currently has a very biased view of the events in Iraq and the news media is unlikely to clear it up, since they have largely moved on. Fortunately, a lot of lessons learned type programs are being made now. These are essentially primary sources and when historians get around to addressing events in Iraq more dispassionately, I believe these will be the key sources.