This is another of my out of order posts. It is from my trip to Rio a while back.

National Basketball Association (NBA) players came to work with kids in the Complexo de Alemão, which just a few months ago was one of the worse and most violent favelas in Brazil. It requires the sustained intervention of the Brazilian army and police to push out the drug dealings and retake control of the neighborhood. They are employing a kind of counterinsurgency strategy that I recognize from Iraq. It is the “seize, hold, build” strategy at work. General Petraeus would understand.

The back story is interesting, as one of the top-cops explained it to me. There was a political reaction against the police and the military after the end of military rule in the middle of the 1980s. One of the dominant modes of thinking explained and to an extent excused crime among poor people as a reaction to the violence and disrespect of the authorities. There were obvious problems with the police at the time and there was merit to the idea that the police should act less as an occupying force and more like members of the community, but what amounted to a partial withdrawal of the forces of order had a negative result. Of course, this is a simplified explanation and nothing ever happens for one simple reason, but this is part of the explanation.

In any case, the favelas were effectively out of control. Movies like “Tropa de Elite” show the situation, no doubt with some cinematic exaggeration, but the fact is that nobody would enter the favelas in safety and the crime spilled out into all regions of the city.

Crime was oppressing not only favela dwellers but spilled into other parts of the city. Some commentators almost seemed satisfied that the quality of life for “the rich” was declining because of the fear of violence, but a storm that wets the feet of the rich often drowns the poor. The rich retreated to walled compounds and hired guards. The poor just got robbed and killed.

The Rio authorities decided to pacify the favelas. They started cautiously, trying to bring services into the favelas, building sport complexes. We had our NBA event in one of those complexes. It was/is a nice facility, but until the police established order, it was a used as drug emporium.

Anyway, even the limited pacification efforts annoyed the drug lords of the favelas, who wanted to keep things the way they were. Evidently to show their displeasure and get the government to back off, the drug gangs started to attack and burn cars and buses outside the favelas, but instead of backing down, the government doubled down. It was a heroic moment. State, local and Federal authorities cooperated to retake the territory from the drug gangs. The Brazilian army literally invaded the favelas, taking them back from the traficantes. Following the forces came services. It was the “seize, hold & build” strategy.

Today police presence remains strong and obvious, but the big story is the return of life and vitality to the favela. I was able to walk freely in places were heavily armed police could not tread just last year.

The authorities have no illusions about wiping out the drug trade. There will always be criminals. But there is a big difference between crime that goes on in the world and actual control of territory by criminal gangs. It was important to secure the authority of the government. When they raised the Brazilian flag on the high point of the favela de Alemão at the end of November last year it was a proud day for the Cariocas and all Brazilians.

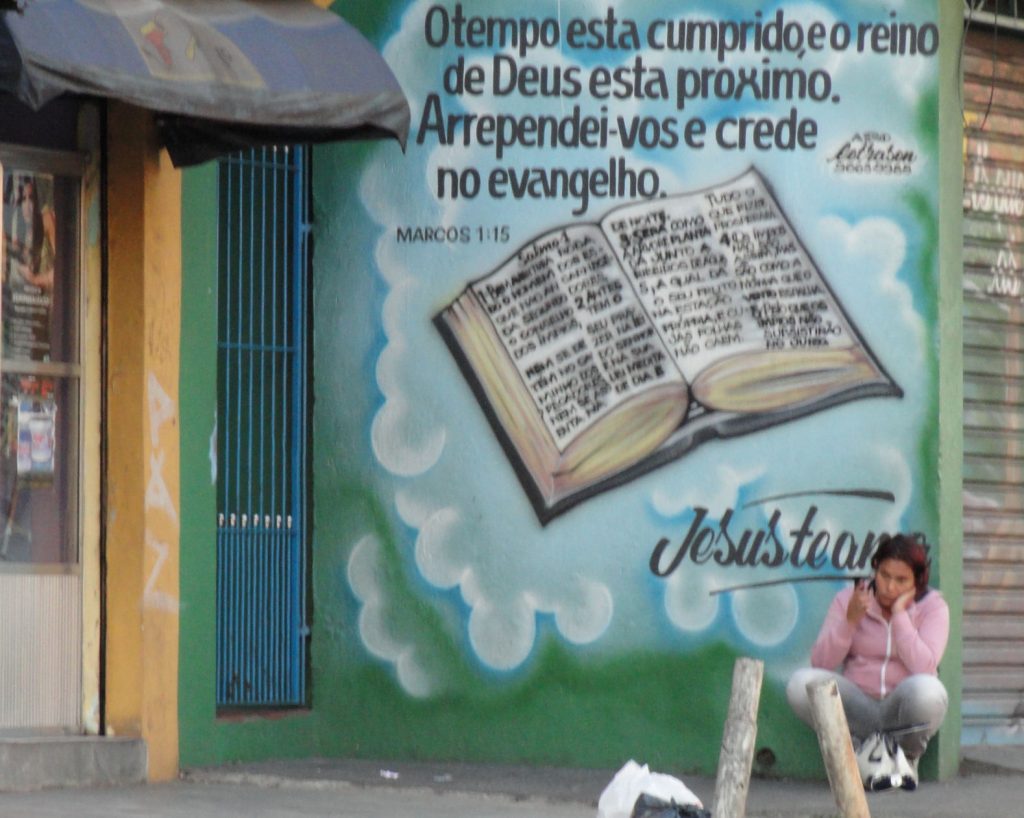

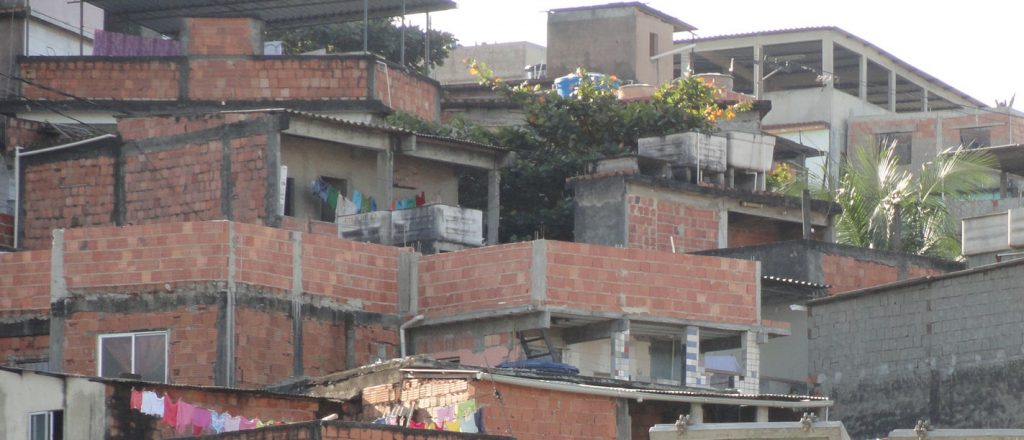

So far, so good. The streets of the favela are now crowded with people and the shops have products in them. There is a chance now. The security has been established, the essential first step. Now the government is making investments in infrastructure. You can see all the workers in the pictures. It is also an auspicious time because the Brazilian economy is growing and providing jobs. But perhaps the most surprising development, one unpredicted by experts, is the dropping birthrate within the favelas. This will give Brazilian authorities and people of Brazil a breathing space to make the changes they need to make in the culture and nature of the favelas.

The pictures are from the favela. You can see the closeup of what it looks like. The favela is a kind of vertical city. It crawls up the hill. It reminds me of those Pueblo Indian dwellings, only much bigger. One guys roof is another’s front yard and walking the streets near the top means climbing stairs and even ladders.