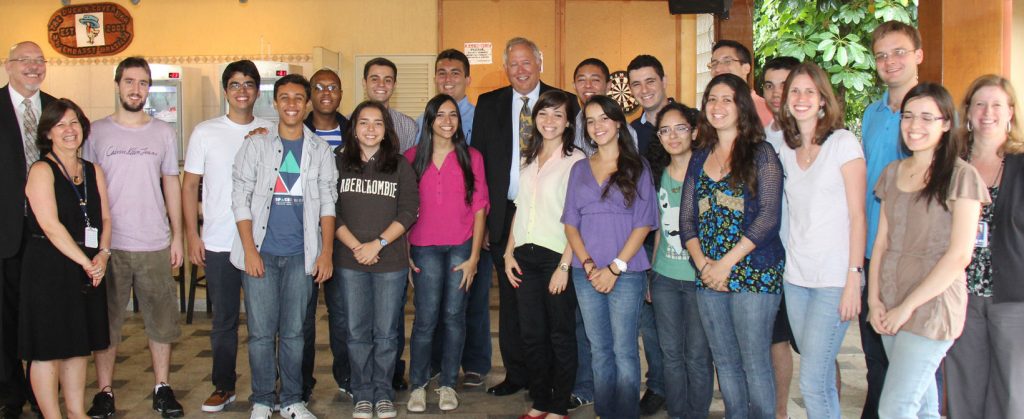

I put the boys on the plane back to the U.S. I talked to Chrissy on Skype. Right now I am watching a nature show with Portuguese narration about New Zealand. New Year Eve party. As you can see the picture up top, I have all I really need.

I do not plan to swim in that whiskey river, at least not very far, maybe one drink when the clock strikes midnight Brasilia time.

I don’t feel sorry for myself. This is my choice and among my preferred outcomes given the other choices. I had several options for New Year events, but I don’t much like the sorts of parties. It goes beyond just being boring, which I suppose I am. New Year has never been a happy time for me. I suspect it is not happy for lots of people, which accounts for much of the alcohol addling that accompanies most celebrations.

When I was a kid, New Year meant that I stayed up late watching the late-late movies. In those days TV was not twenty-four hours. On most days, the stations would sign off around 2am with the playing of the Star Spangled Banner. New Year was different.

My strongest New Year memory is a very sad feeling. It must have been 1972. I had been in the hospital after spiting up blood. Our doctor called it an ulcer. The diagnosis later kept me out of the Air Force. It also ruined my swim team season. I think it was a misdiagnosis, since it never recurred, but who knows. More serious was my mother’s health. We knew there was something seriously wrong, but the (same) doctor couldn’t figure it out. She died of leukemia nine months later. I didn’t know this would happen, but I remember thinking that things would not be the same, if for no other reason that I was growing up.

I went down into the basement, where we had a refrigerator with Coke. Even then I drank a lot of the stuff (even though I was not supposed to because of the “ulcer”). Our basement was a little bit creepy. It was not finished. My father and grandfather had done a little work, but they were usually drunk when they worked and you could tell. It was also full of spiders and perpetually damp, so damp and full of spiders that when my pet newt escaped his terrarium he managed to survive two years down there, with sufficient habitat. When you wanted to turn the lights on or off, you loosened or tightened the bulbs on the ceiling.

It was one of those times when reality just bites. Outside was sub-zero Wisconsin winter and I could hear the wind. The one bulb that I screwed in threw harsh light that didn’t reach into most of the corners. It was around midnight and I was the only one awake. I sang auld lang syne to myself in a quiet voice, not all the words. I didn’t know all the words then and I don’t know them now. And I didn’t know what auld lang syne meant. But I mumbled as much as I knew and then went back up to watch the Late-late movies.

The movies were a strange choice for New Year festivities. TV 6 showed a bunch of World War II movies. I don’t remember details, except that one of them ended with an American soldier in the Philippines trying to make a radio broadcast as the Japanese advanced. He repeated “Manila calling, Manila calling”.

I don’t vouch for all the details of this forty year memory. But that is what I recall.

I spent the New Year 1974 working at Medusa Cement. I was working the night shifts unloading hopper cars. I made good money, but it was cold outside and the work was outside, in the dark. We had to open the bottoms of the hopper cars with heavy crowbars. I couldn’t get a good grip with my gloves on, so I took them off. Cold metal against warm skin gives you a good grip but creates a bit of pain. We would work outside as long as we could tolerate it and then retreat to a shack where we had a kind of propane heater shaped like a torpedo. That thing threw off lots of heat and fumes. My associate, a guy called LC Duckworth, the strongest man I ever met, actually set the leg of his coveralls on fire by trying to warm his feet too fast. I helped put him out.

I most enjoyed riding the cars. We had to push them off and jump on the back, turning the break as fast as we could when we got near the end of the track, which would have taken us in the KK River. It could be kind of exciting.

Our operation was on the river, as mentioned above, from which I could see the clock at Allen Bradley. At the time, this was the largest four sided clock in the world. We used to call it the Polish Moon. Next to it was a temperature sign. As I watched the clock reach midnight on January 1, 1974, the temperature listed was minus five Fahrenheit.

You can see my old cement company as it looks now at this link. Below is the Allen Bradley clock in a different season.

My work during the Christmas break kept me solvent through the spring semester, but I didn’t use all the money I earned wisely. I bought a bunch of booze and held a belated New Year party for my friends. I was determined to enjoy their company w/o drinking myself. I learned that it is impossible to enjoy yourself as the one sober person in a room full of drunks. The jokes just are not as funny. So I decided to catch up. In short order, I drank a full bottle of Tequila and I remember nothing else until the next morning, when I tried to get out of bed, but couldn’t. I had never been so sick before and so far have not been since. I couldn’t actually move around, or even keep down water until around 7pm. Then I was really hungry and thirsty. Tequila used to be my booze of choice, but I have not consumed a drop of tequila since January 4, 1974. Can’t even abide the smell.

A few years later, when I didn’t have a Christmas break job, my friends and I went out to the bars and night clubs. I don’t recall the year, but it was probably around 1976. In those days, you could legally drink at 18 in Wisconsin. We went down to Lincoln Avenue to a place called the President’s Club. I don’t know how we chose it, but it was full of old people. They did not appreciate us and we didn’t enjoy their company, so we decided to go to Crazy Horse, a younger person club near the airport.

I don’t recall why, but our friend Mark decided that he would ride on top of the car, mind you that this is Wisconsin with -10 nights in January. He got up on top of the car, sort of like a deer during hunting season, and hung on for the 2 ½ miles from Lincoln Avenue to the airport. He was never quite the same after that, but you have to respect his ability to hold on. There really isn’t a lot to hold onto on top of a car. Jerry had a Cutlass Supreme, which had landau roof, giving a little more traction, but not that much.

After these experiences, I adapted to a more boring party scene. The only one that really stand out in the latter days is New Year 1985. Chrissy and I were invited to a kind of command performance at a fancy club called Leopoldina in Porto Alegre. It was actually a pleasant time. With a lot of good canape. The place was not far from our house, so we could walk back, making it possible for us to drink more freely. It was a warm night in the middle of the antipodal summer and the place had a pool with a cover on the middle. Our friend Pedro drank a few too many caipirinhas. He jumped in the water and swam under the cover, coming up on the other side, evidently just to prove he could. It was not the usual type of behavior expected at such events. All of us just kind of pretended it didn’t happen – even when it was happening – and never spoke of it again. But the next year Pedro’s invitation ostensibly got lost in the mail.

This New Year will not produce any funny or sad stories. Well, maybe an old guy drinking a glass of Jim Beam chased by Coke Zero is funny or sad, but I am content. “Sou Cesar” is coming on TV. That should take me through the new year.

BTW – if you doubt the theory of evolution, take a look at my boys in the second picture. I kind of expected one of them to pick up a bone and start smashing stuff to the strains of “also sprach Zarathustra”. In fairness, the sun was in their eyes.