It might be a positive sign that there are more hate groups. This is counter intuitive, but according what I learned at at the Southern Poverty Law Center, the number of active, affiliated “haters” has actually decreased while the number of groups has gone up. That indicates a fragmentation of the hate culture. Maybe some people are ostensibly members of several groups and not committed to any. In the 1920s, the KKK had an estimated 4 million members and was organized enough to influence politics at the state level. Today there are fewer than 10,000 members, mostly unorganized losers.

I didn’t know that the Klan of the 1920s recruited most of its members by its anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant stance. In other words, they hated people like my Polish-Catholic grandparents. That probably explains why the Klan was not strong in Wisconsin.

The speaker said that 6-10,000 hate crimes are reported each year. Most of these crimes are now aimed at Latinos and immigrants. Ironically, some of the perpetrators are urban blacks who fear that new immigrants are taking their jobs. This is in many ways a repeat of the anti-immigrant ideas of generations ago and is evidently the hardy perennial of problems.

We have to be very careful in the “hate crime” designation. It is a very broad category that can range from name-calling and vandalism to actual murder. Even in cases of actual violence, the hate motivation is slippery. Murder is always a crime of hate, whether or not those involved are ethnically similar. And as in any broad distribution, the very serious instances get the most attention but are very rare. In a classic case of vividness bias; we more easily recall extreme events and our imaginations turn to frightful images when we may have merely a more comprehensive definition or reporting.

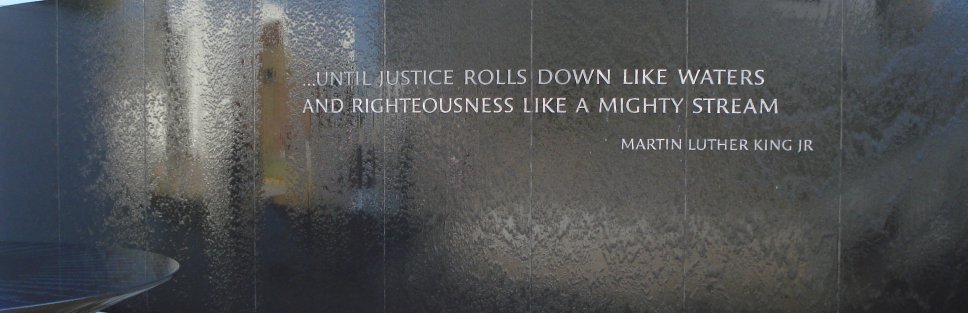

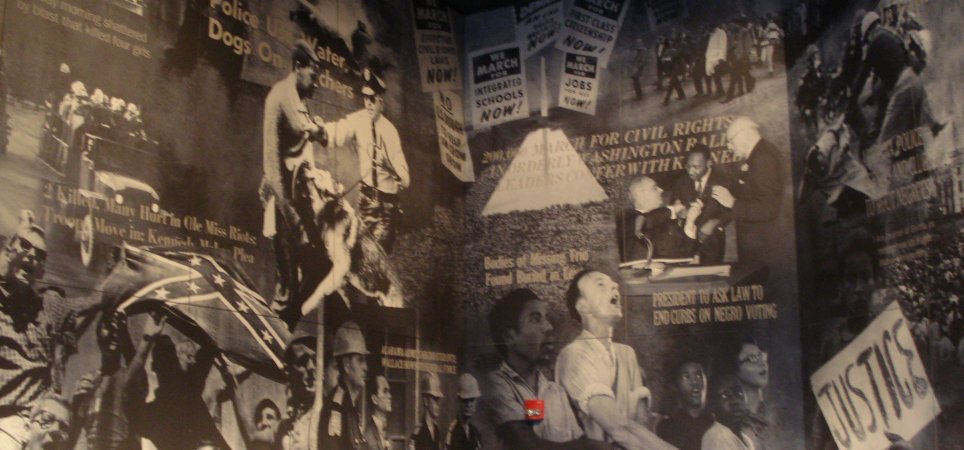

It was much more dangerous in the past to stand up for civil rights in America than it is today and the Institute documented the history of the struggle, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. There was a memorial listing the names of the forty people killed during those decades. Alabama was in many ways the center of the struggle and the struggle was much more black and white and not only in terms of race. When Martin Luther King led boycotts and marches, he was asking only for dignity that most of us agree that all humans deserve. He was success precisely for this reason. He appealed to the humanity, virtue and fundamental goodness of his opponents. Some willing to use firehouses, dogs and worse against protesters, but most suffered pangs of morality. Almost everybody could agree about what was right and wrong.

Non-violent methods work less well against jihadists or dictators willing or even eager to kill hundreds or thousands of innocent people to make their points and maintain themselves in power. In Rwanda, Bosnia, Congo or the unfortunately many other places, murder was/is done on a vast scale and individual voices are silenced before they can be heard, sometimes even when they are heard – and murders are seen in the media – as in the recent case of the Iranian elections the regime rolls on. That is the fundamental dilemma of pacifism. It requires a fundamentally decent society in order to work.

It has become a lot more complicated since then, which is why I think we often hearken back to those days when right and wrong were clearly defined. Forty five years after the Civil Right legislation, it is much harder to know which side is right on debates on affirmative action, racial preferences or even – especially – immigration. The people as the Southern Poverty institutes talked more about immigration than anything else. Maybe it was just because of the nature of our questions, but I suspect that the direction has indeed turned.

IMO, immigration is much more nuanced and problematic as a civil rights issue. Good people can disagree about fundamental values. Of course, individual immigrants are entitled to civil rights and human dignity. But the act of immigration is not a right and an immigrant who enters the country illegally has committed a crime, no matter what we consider the motivations. A country is also entitled to design its immigration laws as it sees fit.

I am generally in favor of immigration, since it strengthens the diversity of our country, but there are plenty of problems I do not want to import. I don’t want immigration that encourages things like the Russian mafia, human trafficking or drugs. Most people would agree with me on the broad direction, but some of the details of procedures and laws would work against this. And clever reading of rules can provide “rights” to some pretty bad people in situations that good people might not have envisioned. I would hate to see the definition of hate expanded to encompass vigorous debate about immigration.

The discussion of immigration inevitably turned to race. Most new immigrants are non-white, but race is not a necessary dominant factor. The focus on race indicates a lack of historical understanding or perspective. There are plenty of reasons to advocate strict immigration rules that have nothing to do with race. I remember when our rejection rate in Poland was over half and as I mentioned above the KKK disliked Polish-Catholics. It just now happens that no European countries now have the growing populations that export people, so that is no longer an issue. The problem with immigration is that immigrants bring different values and often create economic dislocation. Most people want SOME change; not many people want comprehensive change. There is nothing wrong with wanting to keep change manageable or even not wanting much of it at all. America is a great country. It makes sense to be careful when changing a good thing, since usually more things can go wrong than go right.

Frankly I don’t want my country to become more like most countries I have visited in many ways. That is not saying we should just freeze in place. A culture that doesn’t change, dies. I like the America of 2009 better than the America of 1969 in most ways. I just want us to get the best, not the worst of what the world offers. We don’t want to just open the doors and let whoever or whatever come. It is our right to choose. That is why I want rights to remain attached to individuals, not activities, not groups. If you protect the people, other legitimate things follow. It doesn’t work the other way around.