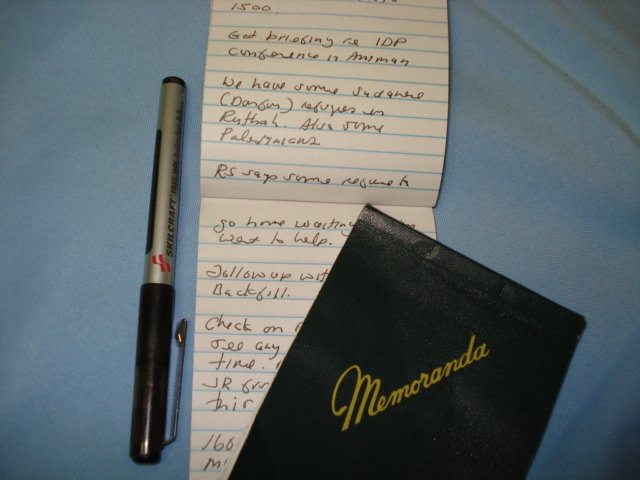

In the background are Hesco barriers. Guess what those things in foreground are.

I truly enjoy the RCT 2 Marine briefings. A lot of information passes but feelings of camaraderie and humor lighten the mood. But it is a special kind of subtle humor, often more conveyed by slight changes in word emphasis (there can be a lot of meaning in a “yes sir”), facial expression or what goes unsaid. I am afraid I will not be able to properly convey it, but I will try with an example. First I need to provide a little background.

The Regiment is in the process of demilitarization – demiling. During the recent unpleasantness, the Marines deployed various types of fortifications. As areas are returned to civil Iraqi control these things must be removed and the place returned to its former condition. This often means barren desert, but it has to be smooth barren desert. The recently demiled desert is usually better than the original, since the smoothing tends to squash down and bury the preexisting garbage. It doesn’t take military action to create a litter problem.

Probably the most common forms of fortifications are Hesco barriers. A Hesco barrier is essentially a barrel of fabric, held in place by wire and filled with dirt and debris. You can see the pictures above. They are easy to make and very good at absorbing explosions but unattractive. The wire is valuable as scrap, but the fabric, which has no salvage value, must be separated. The protocol calls for the fabric to be burned and the metal salvaged. Now that I have set the stage, imagine the scene.

The colonel asks the engineer captain about a particular stretch of road being cleaned up and Hesco barriers removed. The captain explains, “We burn the fabric, sir, to salvage the metal…” The captain pauses. The colonel looks up in anticipation, saying nothing. The captain gets a satisfied smile on his face and adds “… with our flame throwers, sir”. Everybody in the room perks up. The colonel says, “You have flame throwers? Why do you have flame throwers?” The captain answers, “Yes sir. For counter vegetation, sir, we have two flame throwers.” Testosterone surge in the room is palpable. There are several spontaneous offers to help with the flame throwers.

It is true that the flame throwers are good for “counter vegetation operations.” They are very effective in clearing a defensive area around a fortified position. But it was clear from the enthusiasm expressed that using the flame throwers against vegetation or Hesco barrier is a chore nobody avoids.

BTW – in the picture foreground are urinals. You try to hit the pipe. Privacy is not an issue.