My last (for a while) post thinking about global warming. I just finished a two-day seminar on the subject, which is what made me review. There is some overlap in the posts (sorry) but they also can stand by themselves.

The world cannot & will not reduce CO2 emissions any time soon. CO2 we have already emitted will be around a long time and the world will emit more in 2050 than it does now. Experts disagree about how much the earth will warm or the seas will rise, but they will. It is coming and we can do nothing to stop it. So what do we do?

Solve the right problem

We missed prevention and now are in the mitigation and adaption phase. There never really was a prevention opportunity. Prevention was no longer an option by the time we recognized the problem. As late as the 1980s, scientists still warned about global cooling. The current interglacial period was ending, they said. Aggressive government action to reverse that would have been harmful. Decision makers were naturally skeptical when the new -opposite – threat came along. Besides, they were busy dealing with current life on earth threat, ozone depleting chemicals. Anyway greenhouse gas emitting technologies were (and remain) baked into human systems. Real alternatives never had a real chance. (Kyoto was too late and too lame.) So let’s just move on.

After recognizing the true nature of the problem, we should work to avoid the worst-case scenario and reduce emissions to the extent possible. For example, we need to use more nuclear power and generally encourage higher prices for oil and other fossil fuels to promote alternatives. We also need to concentrate on the places where the greatest amount of NEW emission will originate. Europe and the U.S. can work to limit emissions, but the big growth will come from places like China & India.

Stop moralizing

Then stop the moralizing and the panic. Adapting to climate change is an engineering problem. Global warming is not really a mystery. Although we don’t understand all the variables, it is a naturally explained process. It is not the retribution for crimes against Gaia or the wrath of angry nature. Even in its worst-case projections, it is not the biggest change the earth has ever experienced, nor it is the worst human (or hominids) have endured. Our big brains developed in response to earlier episodes of dramatic climate change. We didn’t get to the top of the food chain by being stupid and can adapt to this too.

It was warmer before

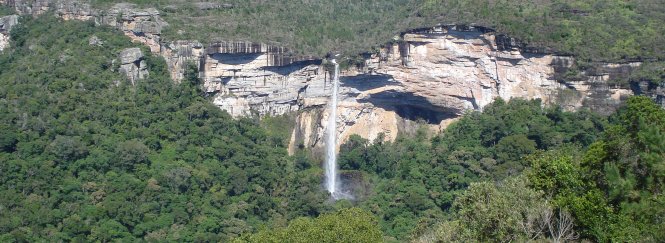

For most of the history of terrestrial life on earth there were no glaciers at all. Temperate forests grew near the poles and tropical rain forests extended well into the latitudes of Canada or Siberia. By all indications, life was perfuse on the warm globe and successful. The problem of climate change is one of location. Plants, animals and humans are adapted to today’s climate. They are not easily moved, but change does not mean immediate destruction. Some forest types in the southern Appalachians or on high ground in the Sonora region, for example, are characteristic very different climates and are relics of conditions long gone. Natural systems can persist for a long time after conditions have changed, but if struck by catastrophes, they may not come back under natural conditions. Human intervention can sometimes create or recreate such ecosystems (if that is desirable).

A tree cannot move, but forests can

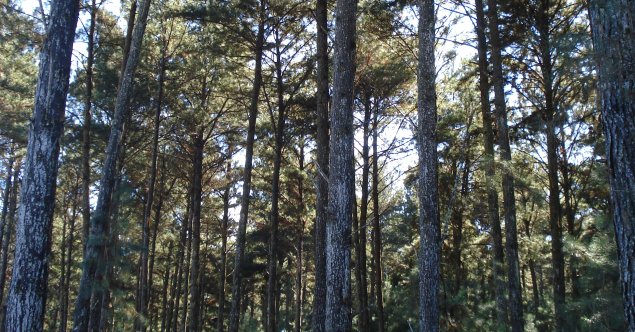

Beyond that, most species of plants and most animals are hardy over large ranges. Most species of trees can grow from Florida to Wisconsin and beyond. The mix is different, but you can find many of the same species in both places. As the climate changes, the mix will change too, but people unfamiliar with forest ecology may not be able to tell the difference.

To mitigate this problem we can facilitate movement. For example, avoid using plants near the southern edge of their range. (My pine trees near the northern end of their natural range will probably grow better in greenhouse conditions.) It is also important to leave corridors. North America has more tree species than Europe. Why? It has to do with the direction of the mountain chains. In N America, the Appalachians and Rockies extend north/south. Eurasia has a fairly consistent mountain mass east/west from the Pyrenees to the Himalayas. During the last ice age, as forest types retreated south, their seeds ran up against high altitudes in Eurasia and many didn’t survive. In North America, this was not a factor. We need to ensure that natural communities can advance north with the climate.

Nature is resilient. What about us?

Our infrastructure and methods of working are built around current conditions. Some of this is not a real problem. No farmer is growing the same crops using the same methods as his father. These are routine changes. Physical infrastructure is a bigger problem, but it is more political or legal than material. It is costly to change infrastructure, but infrastructure does not last forever and is constantly renewed. The problem is the routing. Roads and railroads run through existing right of ways. Moving them may be very difficult.

Location of cities is an obvious challenge, but in most cases we are not talking wholesale relocation. We could mitigate future problems simply by being smarter today. For example, with satellite mapping, we can tell the elevation of a place within a meter and project how much water it would take to flood it. We would be smart to avoid building permanent structures soggy sites. It doesn’t make sense to build on flood-prone places, whether or not we have climate change.

We also need to look at all the options and we Americans don’t have to invent everything. Let’s look to good practices worldwide. Brazil has been working on alcohol fuel for four decades. Arid Australia is a leader in allocating scarce water resources. Although not currently the world leader, it might be India that soon lead the world in biotechnology.

But in the end we might have some great options from the science of biotechnology. Biotechnology can produce plants that require less water, fertilizer and energy to produce. But the connection is even more direct. Biotechnology is already contributing to the production of biofuels and may soon make the production of ethanol from cellulous faster and easier. Cellulose alcohol is the holy grail of liquid fuels. That would mean we could make fuel out waste products such as wood chips or stalks, or from easily grown and ecologically benign crops such as switchgrass.

Paradigms change and we can make them change. If we think only about how things are today, we can never solve our problems. In fact, it is likely that today’s problems CANNOT be solved with today’s methods. We can do it. It requires a leap of faith, but it is a leap of faith in human intelligence and our ability to learn & adapt.

We are standing at a crossroads where our provision of energy, water and food are radically changed. These three factors will be more completely integrated than ever before. All change is difficult, but if done right this one will make all (or at least most) of us much better off and make our lifestyles more sustainable.

A cooler earth?

But perhaps the greatest mitigating thing we ought to do is one we currently do not understand. Can global warming lead to cooling? As the world was warming up from its last ice age (w/o the help of humans BTW) about 11000 years ago, it suddenly got another cold blast. This is called the Younger Dryas stadial. The cause is thought to have been a sudden influx of fresh water into the Atlantic, which interfered with the heat transfer from the tropics to the poles. Some scientist think this could happen again. Although the Younger Dryas event involved the aburpt breaking of an ice dam and a lot more fresh water in a short time, conditions could be similar if glaciers rapidly melt. It would be nothing like the movie “The Day After Tomorrow”, since RAPID change in the real world means it took place over the course of about 50 years and it was not global, but cold temperatures in Europe and N. America would be a problem. An urgent priority would be to understand this mechanism and – if possible – prevent it from doing damage. But currently anything in this subject area is just speculation. My own take on it is that activists want to cover all the bases so that they can blame any weather scenario on human activity.

Always look at the bright side of life

I would make no investments in beachfront property and inhabitants of low islands may consider seeking higher-level opportunities, but we humans have faced worse. As a matter of fact, the Younger Dryas unpleasantness probably forced our ancestors into inventing cereal agriculture. Anyway, we are too far gone down this road to go back and start over. Our options only include things we can do now, not what we should have done before. Whether big events are blessings or curses depends on how you adapt and what happens next.